Why Trump Lost Georgia

What a new way of breaking down the state's political geography says about what happened in 2020 and who will win in 2024.

Editor’s note: This piece is cross-posted from Patrick Ruffini’s newsletter, The Intersection, with his permission. It’s a fantastic political analysis of Georgia. Hope you enjoy it and please sign up for Patrick’s newsletter.

A few weeks ago, I began mapping out a series of posts about the 2024 swing states, looking at the demographic forces shaping a potential Biden-Trump rematch. Georgia, a state Biden won by just 11,779 votes and one now at the center of the four Trump indictments, seemed like the perfect place to start. The results in the Peach State were some of the most striking of 2020: Biden underperformed his final polls in most swing states, but the polls were dead-on in projecting a dead heat in Georgia. In the end, Georgia swung more than 5 points from when Trump won it in 2016, the second highest swing of any battleground state except for New Hampshire.

Initially, this series of posts was going to go heavy on statistics. I meant to use precinct-level results tied to data from the voter file on who voted and didn’t to quantify exactly how many votes were moved by persuasion, and how many were due to changes in who turned out. In the end, I was able to conduct a regression analysis that answers these questions. I won’t spoil it now except to say that the use of mail-in ballots wasn’t predictive at all of a swing away from Trump, something you can add to the mountain of evidence that the Georgia election was not stolen.

But I realized this analysis was incomplete without a better understanding of place. And by place, I don’t simply mean regional differences or the crude segmentation you’ll often find in the media, like metro versus rural areas. We already know, for instance, that most of Trump’s losses in the state happened due to a shift away from him in the Atlanta suburbs. But were those shifts caused by college-educated whites or changing demographics in the suburbs? A more sophisticated breakdown of the state’s political geography than what you’ll normally find was needed to find out.

Georgia’s Ten Political Regions

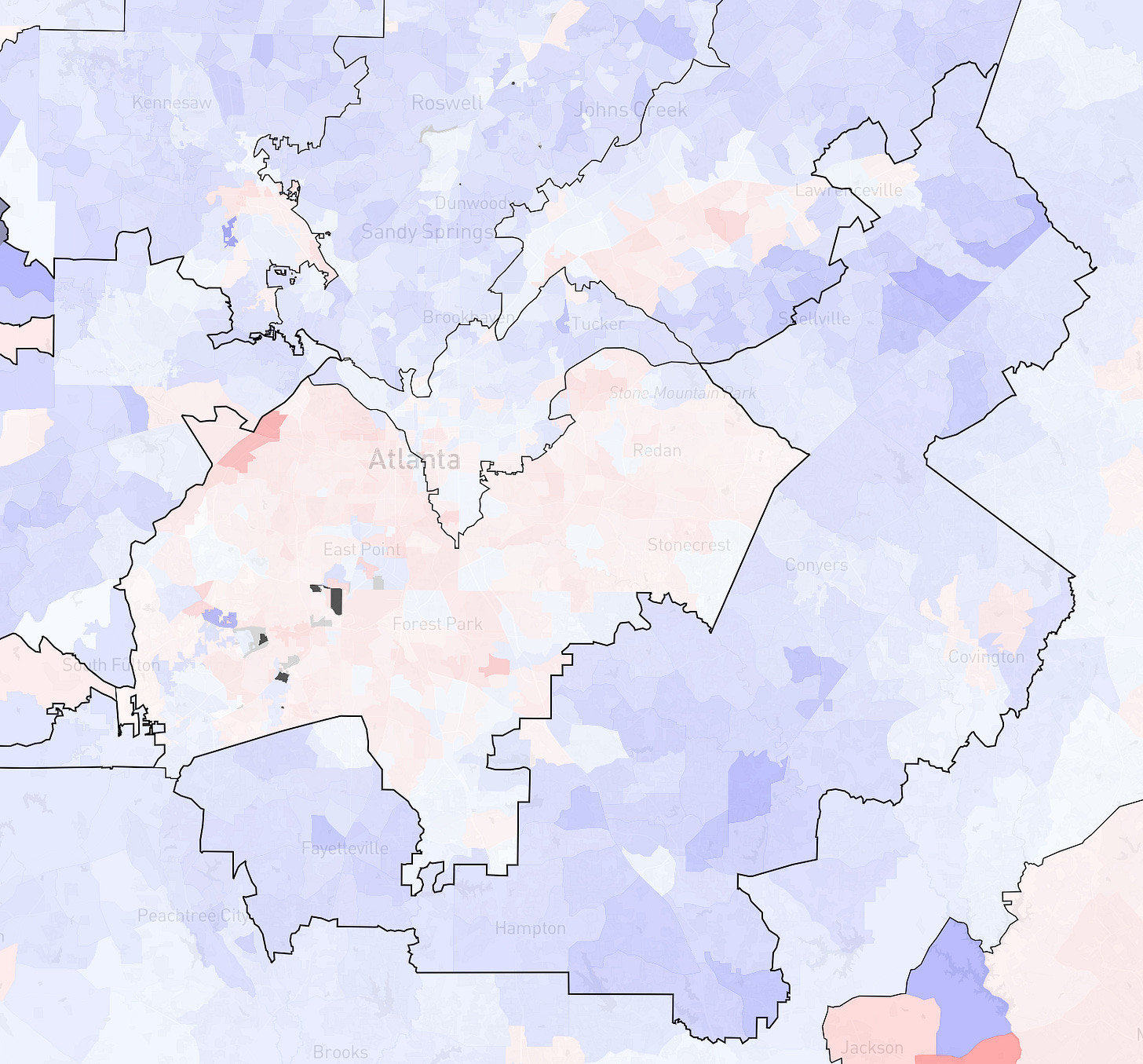

I started the task of building my own classification of Georgia’s political geography with Redistricter, drawing a group of suburban Atlanta precincts where Brian Kemp most strongly over-performed Donald Trump’s 2020 showing. What immediately stood out was the precincts where Kemp did a lot better than Trump tended to also share other demographic characteristics in common. They were wealthier. More highly educated. They had the highest percentage of workers employed in IT, finance, insurance, and real estate. And these wealthy, well-educated suburbs were the exact place where Republican support collapsed the most between 2012 and 2016. They’re the setting for this banger of a piece from Ben Jacobs, set partly in the Whole Foods in Sandy Springs, appropriately titled, “Are Never Trump Republicans actually just Democrats now?” Behold our first group: the Rich Men North of Buckhead.1

Amongst the Rich Men, 10 percent of the state’s electorate, Brian Kemp outperformed Donald Trump on a two-party basis by 15.4 percentage points, nearly double his over-performance statewide. Kemp ran fully 20 points ahead of Herschel Walker, his ticket-mate in 2022. The area swung nearly 13 points left from 2016 and 2020, more than any other geography in the state except one. And on the margin, Trump did fully 37 points worse than Mitt Romney did in 2012, by far the worst figure of any region.

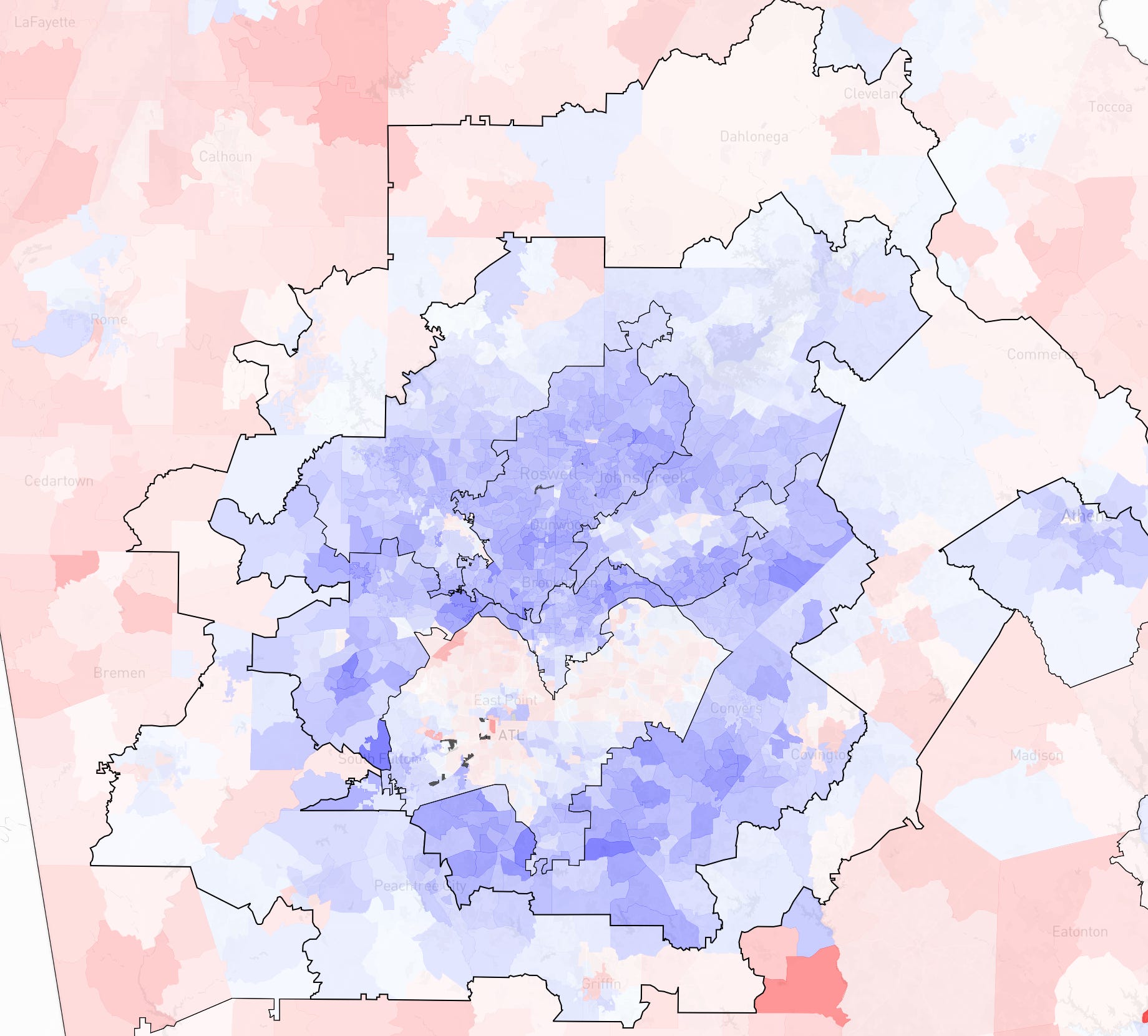

So, I continued to draw, looking for clusters like the Rich Men that were similar to each other across numerous different dimensions—including voting patterns, swing between different elections, race, education, income, housing costs—and Redistricter made this super-easy. The basic test was: Does this area seem to behave politically as a unit? And if there are a manageable number of units, and understood their relative sizes and tendency to swing from election to election, we’d then have a better mental model of how a state as a whole might behave than focusing lazily on trends within certain counties or demographics, without reference to their size or to countervailing trends elsewhere.

The custom regions are collections of precincts, not counties. And geographic contiguity is not a hard and fast rule—though in Georgia political divides are consolidated geographically to a degree unusual in other places, influenced even by soil type. But, outside of Atlanta, it made sense to tie together wealthier urban and resort areas spread throughout the state because they had more in common with each other than their surrounding rural areas.

Enveloping the zone inhabited by the Rich Men are their cousins from the Diversifying Suburbs representing the largest group of voters statewide, 16 percent of the major party vote in 2020. The region covers most of Gwinnett County, northern Cobb County, and much of Cherokee, Forsyth, and Hall Counties. Here, Trump’s two-party margin fell by 11.3 points from 2016 to 2020, though he still managed to win the area by 9 points while losing the Rich Men by 8. The longer-term trend since 2012 hasn’t been quite as brutal for Republicans—a loss of 23 points—but it seemed to accelerate between 2016 and 2020. The area is not quite as highly educated—40 percent of adults aged 25+ have degrees compared to 68 percent of the Rich Men, and household incomes over $200,000 are less than half as common. What also differentiates this suburban zone is its diversity—with an Hispanic voting age population of 19 percent and a black population of 16 percent—and these groups are growing, especially in Gwinnett. And while the most Hispanic areas around Lawrenceville swung right in 2020, the sheer growth of these demographics replacing an older white population has shifted these precincts left. The white voters in these suburbs remain very conservative—I estimate they voted for Trump by 40 points and that’s in contrast to a mere single digit Trump advantage among whites in Rich Men territory.

Demographic change is really the entire story in the southern part of the Atlanta metro, the historic home of the city’s black community. If you’re looking for a reason why Joe Biden underperformed his 2020 polling in almost every other swing state, but he didn’t in Georgia, the growth of the state’s black population is a key reason why. The in-migration of blacks to the Atlanta suburbs is unduplicated almost anywhere else in the country. And it’s centered around places like Henry County and southwestern Gwinnett County, where the population is turning over rapidly.

In Black Atlanta, a demographically stable group of precincts representing 9.5 percent of the statewide vote on the south side of Atlanta and in the close-in suburbs, Trump bucked statewide trends and gained a couple of points in margin from 2016—while still losing the area by 84 points. But in the adjacent areas of Black Suburban Growth (11.1 percent of the vote), the 2016-20 election swing was worse for Trump than practically any part of the country, where he lost fully 14 points in margin. Urban Atlanta results show that it’s unlikely for Trump to have lost significant ground with individual African American voters. Rather, the population of these areas is changing rapidly, fueled largely by a reverse Great Migration to the South of African Americans. When we talk about the precincts that have shifted most in recent years, they are specifically those depicted below, bordering black Atlanta to the south and west, where the blue trend was strongest.

This trend is worth further examination as it is unique in the nation—and may significantly affect the ability of the Republican Party to hold on in Georgia, especially with a weaker candidate like Donald Trump.

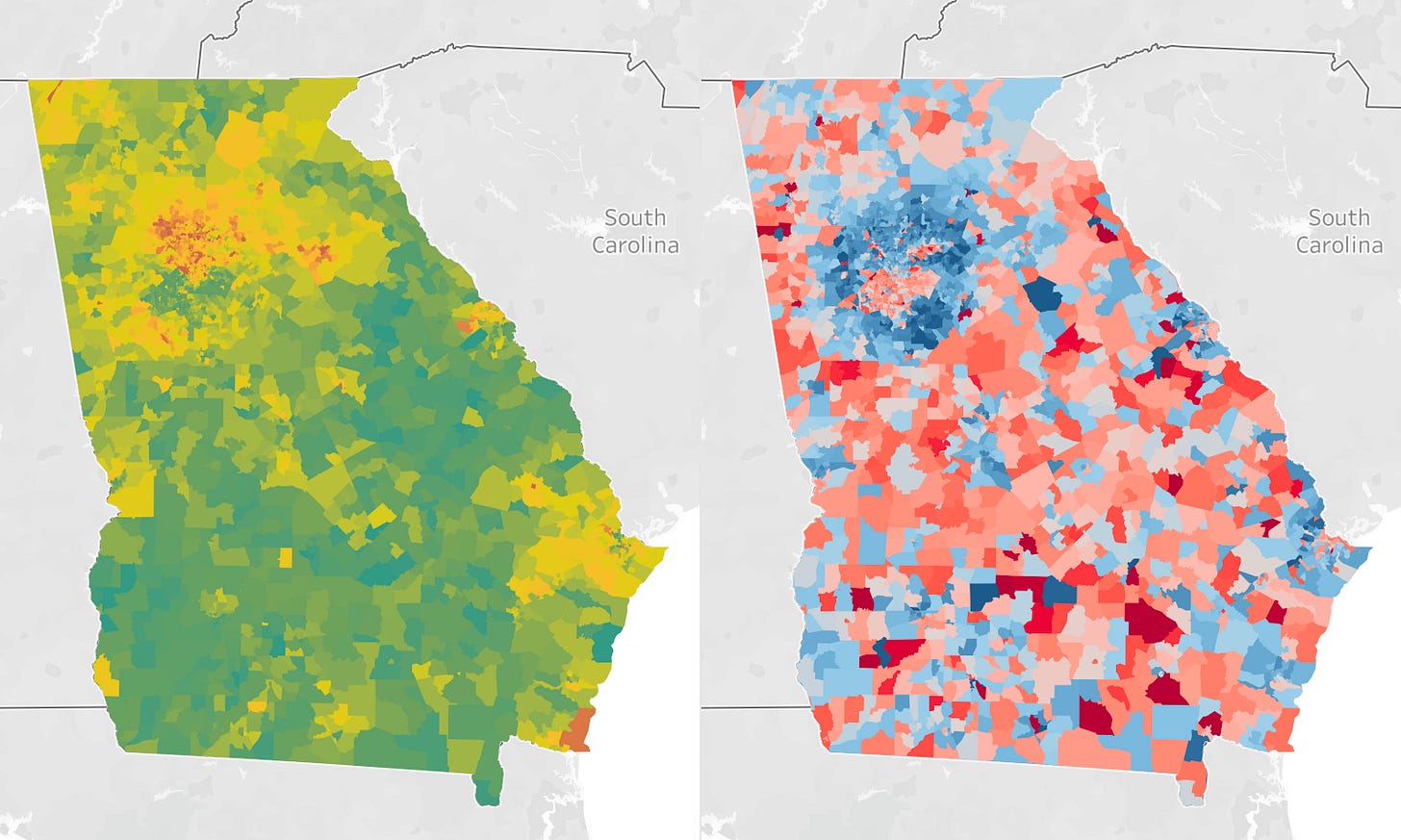

From 2010 to 2020, the black adult population Georgia grew by 18.5 percent. The white adult population, meanwhile, grew by just 2.6 percent. If you compare this to another swing state, North Carolina, which has swung back right after voting once for Barack Obama in 2008, the black adult population growth in the last decade was 9.5 percent while white adult growth was 4.5 percent, a much narrower gap than in Georgia. Indeed, if we map the change in the black share of the adult population county by county throughout the entire South, the southern ring of counties surrounding Atlanta immediately stand out. The magnitude of this black population gain is greater in Atlanta than anywhere else in the country with the possible exception of the Dallas suburbs. And it’s magnified by the fact that Georgia whites are still extremely conservative, voting for Trump by a margin of around 50 points, with college educated whites supporting him by a margin of 40 percent. Including more and more of a 90-10 Democratic voting population in this mix can make for some dramatic shifts, even on a 2- and 4-year time horizon.

Before we completely depart the Atlanta region, it’s worth mentioning one smaller region: Cosmopolitan Atlanta, directly to the south of the Rich Men. This is a highly educated and very blue area that’s home to Georgia Tech and Emory University. Trump lost it by 64 points and there was little room for him to fall much further here: he lost it by just 5 points less in 2016 and Kemp also lost it by 5 points less, in contrast to an almost double digit over-performance statewide.

Going further afield in the Atlanta metro, we now enter the Metro Borderlands, a circular ring encompassing the metro itself. It produces 9 percent of the statewide vote, and voted Trump by 45 points. Encompassing relatively far-flung towns, from Peachtree City to the south to Cleveland in the north, it encompasses the furthest reaches of Atlanta sprawl. And the subdivisions that have started to pop up here have chipped away slightly at Republicans’ advantage here: it moved 6 points left from 2016 to 2020.

As an “in between” area, the Borderlands are more internally heterogeneous than many of our other groups, though still quite a heavy shade of red. The basic splits are these:

Any precinct touched by a subdivision, especially to the south, shifted 10-15 points left between 2016 and 2020.

White rural precincts, especially to the north, basically stood pat.

Heavily black small town precincts, like the ones in Griffin highlighted below, swung a few points to the right—more decisively than the mostly black urban and suburban precincts.

Leaving the Atlanta metro, we start first with the state’s most Republican region, what I call the Northern Highlands. This is Marjorie Taylor-Greene country. It’s also very, very white, with just a 6 percent black population in a state where the black electorate is pushing 30 percent. It voted for Trump by 58 points, and those margins have increased some from Obama-era levels. It’s also growing quickly, defying the stereotype of emptying-out white working-class heartlands. The level of incomes at $200,000 and above stands at just over one tenth that in Rich Men territory and just 19 percent of adults have bachelor’s degrees.

The most cosmopolitan of the non-Atlanta groups is called Southern Comfort—a geographically disparate set of small city neighborhoods distinguished by higher levels of education and income, including everywhere from the college town of Athens to the resort and retiree-heavy areas of Savannah, Augusta, Lake Oconee, and coastal Georgia. It also includes much of Macon and Warner-Robins, and some areas of Albany. Here, we find a slightly more muted version of the political shifts in the Atlanta metro—8.5 points more Democratic since 2016, 22.5 points since 2012. Its raw vote count has grown 31 percent since 2012, compared to 40-plus percent in the Diversifying Suburbs and Suburban Black Growth. It cast 11 percent of the statewide vote in 2020.

One of the two regions surrounding these islands of prosperity is the largely rural Black Belt. The title here is slightly misleading: the region is only about half black. And outside of a few urban neighborhoods, there’s a relatively low level of racial residential segregation, with blacks and whites living in close proximity in rural areas throughout the region. But this proximity belies highly racially polarized voting. Black adults outnumber white adults by 1 point and Biden voters Trump voters by a nearly identical 4 points. The Black Belt is one of four regions—including Southern Georgia, the Northern Highlands, and the Metro Borderlands, where the white vote for Republicans ranges upwards of 80 percent. This fact alone helps explain why education polarization in the South hasn’t helped Trump: there are few non-college white Democrats to flip, but a lot of upside for Democrats in flipping still very Republican college-educated whites.

The Black Belt shows few signs of changing: voting here is more stable, shifting 2.2 points right, the same as Black Atlanta. Ticket splitting is low here, as it is in the other rural regions. Kemp outperformed both Trump and Walker, but by nowhere near as much as the northern Atlanta suburbs. These two historic centers of the African American population also have the lowest vote growth in the state by a good bit—8 and 14 percent respectively since 2012. Black population growth is being redirected to the suburban growth zones, which have grown 41 percent in raw vote terms since 2012. The Black Belt is the state’s poorest region and college graduates make up just 16 percent of the population.

The Coastal Plains are our final region. The line between them and the Black Belt is largely drawn by black settlement patterns, and the region is whiter, but not completely so, with a decently sized black population spread throughout and a 60-29 racial split among the voting age population. Like the Black Belt, it was drawn to encompass the bulk of the rural and working class vote in this part of the state, including urban black neighborhoods in cities like Savannah. The region backed Trump by 27 points, indicating racially polarized voting patterns, also closely matching the white demographic majority. Aside from the Black Belt, it’s the region that’s swung the furthest right since 2008.

What mattered in 2020

Statewide, the 5.3 point shift between 2016 and 2020—just enough to tilt the state to Biden—was driven by three factors: 2016 third party voters switching to Biden in 2020; black population growth and white population decline; and persuasion, primarily among high-income, high-education voters.

To figure out which of these factors mattered more or less in shifting the state towards Democrats, I ran a precinct-level regression model testing numerous variables from past election results, eventually distilling them to highly significant ones grouped around these three main causes. Let’s dig in further.

2016 Third Party Voters

The relative absence of third parties in 2020, in contrast with the more robust third party support seen in the Trump/Clinton match-up was enough to shift the overall margin by 1.88 percent to Joe Biden, just over a third of the overall shift. That’s out of a 3.5 point decline in third party support in four years, implying that Biden received three in four 2016 third party voters. I find this by holding the 2016 third party vote variable to the 2020 level of 1.29 percent statewide, effectively taking 2016’s “extra” third party voters out of the equation.

But there’s something curiously strong about this relationship: It holds—though to a smaller degree—even when modeling the change in Donald Trump’s share of the vote, meaning more 2016 third party votes is associated with Trump 2016 voters switching, not just third party voters. What’s happening here?

A map of 2016 third party votes in Georgia, lined up with 2016-20 swing, provides a clue. The 2016 third party vote was much higher in Rich Men and Southern Comfort territory, exactly the same areas moving away from the Trump-era GOP generally. Third party support in 2016 was likely a cleaner proxy for soft Trump support that year, so some of this effect—about half a point—reflects switching from Trump to Biden, rendering a net 1.4 point shift to Biden the conservative estimate of what he netted from 2016 third party voters.

2016 Third Party Support & 2016-20 Election Swing

Demographic Change

Just as the regional analysis showed the areas of rapid black suburbanization zooming left, so too does an individual-level analysis of 2016 and 2020 turnout. I did this by looking at the precinct-level racial makeup of 2016 general election voters and 2020 voters. This analysis has some limitations, as it looks at voter file records of 2016 vote history as they were in 2020, not 2016. But Georgia has relatively complete racial data on the voter file, so this analysis goes further than it might in other states.

Overall, changing white-black racial demography moves the margin 1.55 points in Biden’s direction—a number found by holding racial demographics by precinct consistent with 2016 levels. That’s notable as it’s a factor unique to Georgia and not found in states throughout the South. This map of white population growth and (mostly) decline adds another dimension to the swing analysis. In the areas with the sharpest drops, Gwinnett and Henry Counties, voting has moved sharply to the left. It’s notable that the growing population from other racial and ethnic categories—Hispanics and Asians—has no effect on growing Biden’s margin. This is likely because their increased population totals are offset by the well-documented swing to Trump among these voters in 2020.

2016-20 White Voter Percentage Growth/Decline vs. 2016-20 Election Swing

This does not mean that black turnout was decisive for Biden, though. Changing racial demographics were mostly a function of new voters moving in, mostly to the Black Suburban Growth zone. In fact, when measuring actual 2020 election turnout against a pre-election turnout model, black turnout almost exactly hit its marks, but white turnout was 2 percent higher than expected. So, black turnout lagged white turnout compared with expectations, but there was a bigger pool of Democratic-leaning black voters to draw from.

One thing that may have helped Biden overall is higher turnout rates across the board. Holding the raw vote increase consistent with the national level of 16 percent (as compared to the 21 percent growth in Georgia), further shifts the margin by 0.66 points in Biden’s direction. This effect appears stronger outside the Atlanta metro—particularly in Southern Comfort territory—than inside it. This might be due to changes in the nature of the white population in these areas—more white retirees from the north, relatively fewer white conservative Georgia natives.

The shift accounted for so far is 4.1 points out of 5.3 points. Of these, 2.2 points come from changes in who turned out, factors that are mostly specific to Georgia, explaining why Biden did well there relative to the national baseline.

Persuasion

All of this leaves persuasion—defined here as Trump or Clinton 2016 voters switching their votes. The net effect of this is the remainder of the shift not already accounted for. Some of this can be measured with income and education variables: the patterns of how votes changed in high-socioeconomic (SES) versus low-SES areas create a modest pro-Biden swing of 0.59 points; again, this is achieved by setting every precinct at the median SES level. Controlling for other variables, the total spread in swing between the richest areas and poorest areas was about 10 points. All else being equal, the poorest parts of Georgia swung towards Trump by 3 points and the wealthiest swung away from him by 7 points.

The rest, approximately 0.6 percent, is either random variation or factors not able to be accounted for in the voter file or election result data (which could be numerous, and cancel each other out in both directions).

Technically, vote switching from third party candidates also counts as persuasion. And there was that part of the third party swing that also showed up in a reduction of Trump’s vote share, accounting approximately 0.5 percent of the initial 1.9 percent swing tied to 2016 third party voters, so that can technically be added to this column if one prefers. And if one totals up all persuasion, whether from third parties or from Trump, the total shift in Georgia due to persuasion is about 3.1 points—and 2.2 points comes from the changes in the composition of the electorate.

Implications for 2024

How does all of this bear on how Democrats might look to hold Georgia in 2024—and Republicans might look to win it back? A few thoughts on that follow.

From a Republican point of view, the results of recent federal elections are a relative outlier. Trump lost and MAGA-inflected candidates like Herschel Walker did also, but Republicans had no trouble winning every other statewide race in 2022, and the House popular vote by 4 points.

Most of this over-performance happened in a few select regions where Republicans would do well to concentrate. Fully 4.5 points of Brian Kemp’s 7.8 point over-performance compared with Trump—or 58 percent—came from just three regions: The Rich Men North of Buckhead, Diversifying Suburbs, and Southern Comfort, which cast 37 percent of the statewide vote. These regions made positive distinctions between other Republican candidates and Trump/Walker, and especially so for Secretary of State Brad Raffensberger, whose taped conversation landed Trump in hot water with the Fulton County DA. If a non-MAGA Republican candidate would lose the votes of Trump supporters, it was not evident in Raffensberger’s 2022 showing. Raffensberger ran even further ahead of Kemp (not to mention Trump) in every region. The only places voters didn’t really make a positive distinction for Raffensberger came in the very Trumpy Northern Highlands and Metro Borderlands, but Raffensberger’s stance against 2020 election lies did not cause him to underperform the rest of the GOP ticket anywhere.

However, this path likely depends on the GOP not nominating Donald Trump, or suburban voters coming to see a Trump-Biden rematch in a new light. We shouldn’t necessarily bet on either of these things happening.

Georgia as a whole is not demographically favorable to Donald Trump: unlike the upper Midwest, there are fewer white working-class voters left for him to flip, and a lot of cross pressured college-educated white Republicans. There’s a reason why Ron DeSantis did particularly well in matchups against Trump in Georgia back when he was riding high. Add to that Trump’s relentless attacks against the state’s popular Republican leaders.

If Trump’s path with suburban whites is closed off, Trump has another option: continuing to chip away at Democratic margins among African Americans, as current polls suggest he might. This is essentially what he did in 2016, helping him win North Carolina and Georgia, the latter by a comfortable margin. Lower turnout would also help Trump, since more the lower-turnout non-college electorate is nonwhite. Cornel West making the Georgia ballot could add another wrinkle for Biden, though the threshold for third party ballot access is high. Nonetheless, Trump would likely need a bigger breakthrough with black voters than he’s gotten to date to fully counteract the effect of the state’s black population growth. Polls suggest such a shift might be in play, but we shall see.

As a state on the knife’s edge in 2020, Georgia will likely once again be a center of attention in 2024. I confess myself to be more pessimistic about Republican long-term prospects here than I am in other states—unless Republicans manage to score a breakthrough with black voters. The changing demographics of the state—unique amongst big states—is uniquely challenging for Republicans. And Republicans could have further to fall in the northern suburbs. Republicans do have a buffer, though, in residual goodwill for the Republican brand as a whole, one they could tap into to overturn the state’s razor-thin margin from 2020.

Patrick Ruffini is a pollster @EchelonInsights and the author of Party of the People coming in November 2023.