White Non-College Voters Don't Oppose Social Welfare Programs

How misperceptions among progressive elites block unified coalitions to help all working-class communities

If you drop into any progressive discussion group these days, or pick up the New York Times, you’ll hear nonstop chatter about the “race-class” dynamic and how white people’s racism, stoked by nefarious elites, prevents them from supporting policies that would reduce inequality. This is probably the most fashionable theory in all of left politics these days.

But the entire theory is built on an assertion, not empirical reality. Do white working-class voters oppose the safety net and economic support systems? No, they do not.

Multiple public opinion studies on anti-poverty programs and basic attitudes about government support for low-income people show that most white non-college educated voters back these interventions and oppose efforts to reduce them.

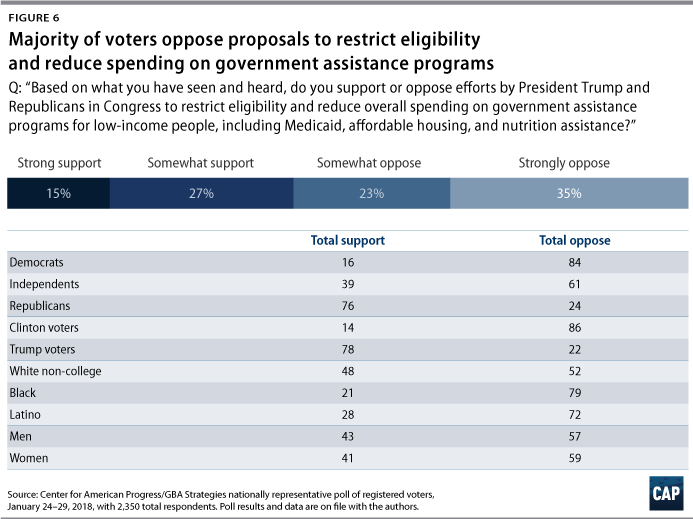

For example, a project I helped to develop in 2018 explored voter reactions to a range of proposals in the Trump/GOP budget to slash and restrict the safety net. Ideology and partisanship emerged as the defining lines for support or opposition to anti-poverty programs, not race.

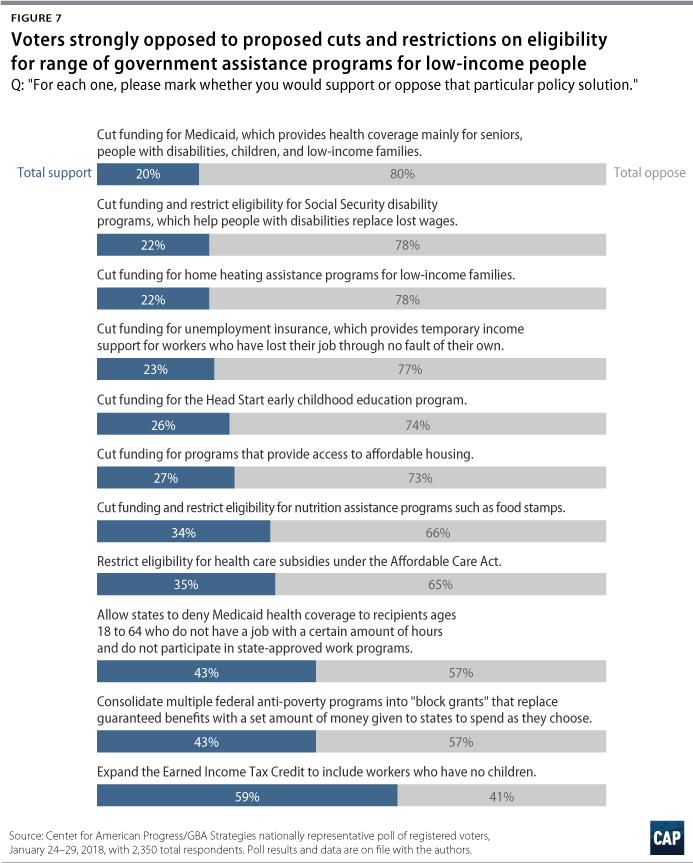

As seen in the above figures, all but the most conservative voters rejected proposed cuts to health care, housing, education, disability, and food stamps while a strong majority supported expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit, the leading low-wage income support program.

Given the reigning “white people vote against their interests because of racism” theory, a majority of non-college whites should be in favor of slashing the safety net and restricting eligibility for government programs, not in opposition to these efforts. But that is not the case. Although opposition to cuts is not as high as it is among black and Hispanic voters, most working-class whites—a huge chunk of the national electorate and even more in key battleground states—align with other Americans on the importance of protecting social welfare policies.

Obviously, race has historically played a role in reducing support for redistribution and safety net programs. And non-college whites do express higher than average concerns about fraud and abuse in the welfare system, while also emphasizing the need for personal responsibility. But contrary to progressive orthodoxy, this is not entirely racialized. For example, working-class whites in focus groups I’ve conducted tended to fault members of their own families, or those in their neighborhoods, for a lack of effort or attempts to game the benefits system—not black or Hispanic people. In turn, working-class black and Hispanic voters expressed similar concerns about members of their own extended families and communities.

People working full time jobs, regardless of race, want to help other people facing low wages, unemployment, and high costs—assuming they are doing their part and acting responsibly.

The recent decades of rising inequality, stagnant wage growth, and multiple economic crises have hit working people across the country particularly hard.

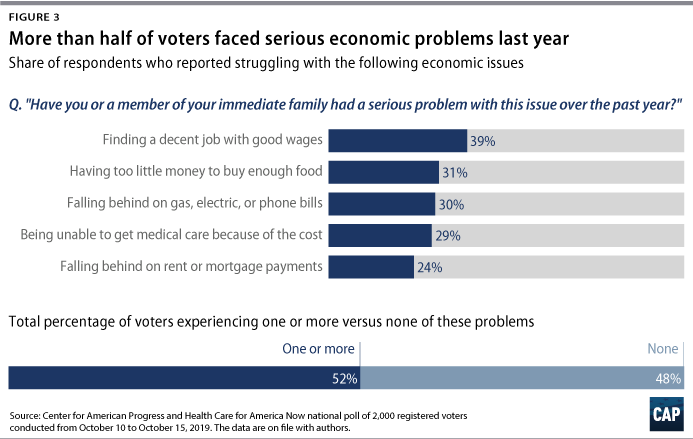

Consequently, as seen in the figure below, a large percentage of Americans face financial insecurity or hardship on a regular basis, with anywhere from one quarter to more than three in ten Americans (pre-pandemic) reporting difficulties in the past year affording basic bills, paying rent, affording food, and getting necessary medical care.

Let’s put all of these working-class and low-income people at the center of our politics and stop pitting them against one another based on theories often disconnected from reality.

They need our help, not scorn.