When Science Journals Become Activists

Spinning climate data to fit a policy agenda undermines public faith in science.

Public trust in many mainstream publications continues to consistently decline. Part of the reason for this seems to be that media outlets cater more and more to the ideological tastes of specific groups, sacrificing their credibility to a wider audience in the process. I have criticized the New York Times, for example, for exaggerating the impacts of climate change, but this type of criticism may be in vain if they are covering climate exactly how their audience wants them to.

It is in a media environment like this, however, that we desperately need reputable sources of scientific information. Sources that will avoid the same temptation to cater to their audiences and prioritize dispassionate reporting of facts instead.

Nature magazine has a reputation as one of the most reliable sources of information on earth. Their publication has a section of peer-reviewed articles as well as softer sections dedicated to science news and the like. I have criticized the landscape surrounding high-impact peer-reviewed scientific studies published in places like Nature, but I won't elaborate on that here. Here, I want to bring attention to Nature’s science news section. Sadly, this section now appears to be engaged in similar levels of spin on climate information as outlets like The New York Times.

Two recent articles serve to illustrate the point.

The first is titled:

Surge in extreme forest fires fuels global emissions. Climate change and human activities have led to more frequent and intense forest blazes over the past two decades.

The second is titled:

Climate change is also a health crisis—these graphics explain why…Rising temperatures increase the spread of infectious diseases, claim lives, and drive food insecurity.

Between these two news articles, we have four claims: one on wildfires, one on infectious disease, one on deaths, and one on food security. Let’s scrutinize each claim one by one.

Are wildfires and their carbon emissions increasing?

The title and subtitle of the first article conveys the impression that global wildfire activity is increasing, which in turn increases CO2 emissions from wildfires. This idea is also communicated several times in the text of the article (emphasis added):

“Global forest fires emitted 33.9 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide between 2001 and 2022…Driving the emissions spike was the growing frequency of extreme forest-fire events.”

“Xu and her colleagues found that the growth in emissions had been mostly fuelled by an uptick in infernos on the edge of rainforests between latitudes of 5 and 20º S and in boreal forests above 45º N.”

“The increased numbers of forest fires was partially driven by the frequent heatwaves and droughts caused by climate change”

The article also goes on to raise the concern of a self-reinforcing feedback loop:“In turn, the CO2 emitted by forest fires contributes to global warming, creating a feedback loop between the two.”

There are, of course, many positive and negative feedback loops in the climate system (i.e., responses to warming that either amplify or counteract the initial warming). The relative sizes of these feedback loops are systematically documented in synthesis reports like those from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. According to the IPCC, the CO2 feedback associated with fires is very small relative to other feedbacks. To put it in perspective, it is only about three percent as large as the water vapor feedback (as the atmosphere warms, it can “hold” more water vapor, which is a greenhouse gas, that further enhances warming). Thus, a self-perpetuating cycle of warming leading to more fires and more CO2 emissions is not exactly at the top of our list of concerns.

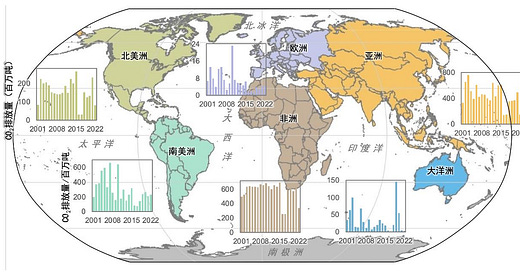

Second, and more importantly, despite what is communicated in the article, global CO2 emissions from wildfires are not actually increasing! The Nature article covers a recent non-peer-reviewed report by the Chinese Academy of Sciences that contains one figure on changes in wildfire CO2 emissions over time (with emissions separated by region):

This figure does not indicate an increase in global emissions over the study period (2001-2022).

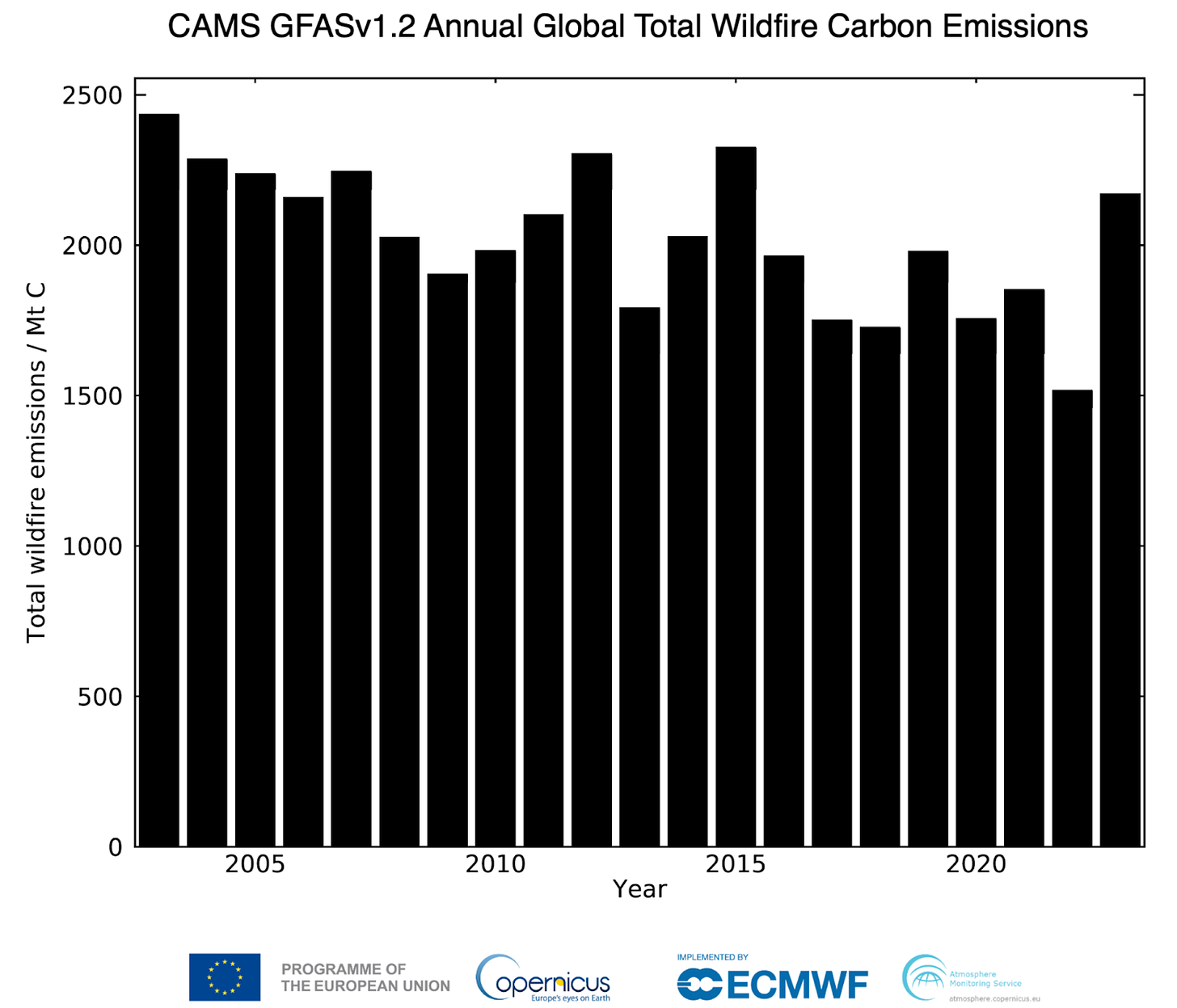

Independently, the most well-known estimate of CO2 emissions from wildfires comes from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), Global Fire Assimilation System (GFAS). This estimate shows a decrease in global wildfire carbon emissions over its record (dating back to 2003):

This reduction in carbon emissions is also in line with a long-term observed decrease in the annual amount of global land area burned by wildfires:

Since all these numbers seem to contradict what is communicated in the Nature article, I emailed the author to get some clarification. She told me that:

Based on my interview with Xu Wenru, a co-author (of the Chinese Academy of Sciences report), extreme forest fires became more frequent over the past 22 years in areas prone to forest fires (on the edge of rainforests between 5 and 20º S and in boreal forests above 45º N), and their CO2 emissions increased rapidly.

But this amounts to saying that CO2 emissions from wildfires are increasing…where CO2 emissions from wildfires are increasing. And it completely leaves out the important context that global CO2 emissions from wildfires are decreasing.

Are rising temperatures causing an increase in deaths?

The second article at least implicitly claims that rising temperatures are leading to an increase in overall deaths directly attributable to the health impacts of non-optimal temperatures.

“People are dying from heatwaves caused by climate change every year.”

The claim can be traced back to a 2023 Lancet report. To calculate heat deaths, they use what I consider to be a dubious method of first calculating the frequency of days that cross a locally defined heatwave threshold and then relating that frequency to deaths. I’ll put my skepticism of this method aside for now and instead focus on two more glaring omissions.

The first is that warming’s influence on cold-related deaths is completely ignored. It turns out that cold temperatures are associated with roughly 9 times more deaths than hot temperatures globally. Below are estimates of annual average cold-related and heat-related deaths from 2000 to 2019 in different regions of the world:

Given the disproportionate burden that cold temperatures place on human health, it is perhaps not surprising that since 2000, warming has caused a larger decline in cold-related deaths than an increase in heat-related deaths—meaning that deaths have declined overall.

The second major omission is that even when heat deaths are considered in isolation, those deaths are declining over time because societies are becoming less sensitive to temperature faster than temperatures are rising. Here is how the IPCC puts it:

Heat-attributable mortality fractions have declined over time in most countries owing to general improvements in health care systems, increasing prevalence of residential air conditioning, and behavioural changes. These factors, which determine the susceptibility of the population to heat, have predominated over the influence of temperature change.

However, the Nature article and the underlying Lancet report simply fail to mention cold deaths or decreasing societal sensitivity at all.

It may be technically true to say that people are dying from heatwaves caused by climate change every year, but this statement clearly leaves out the full story.

Is malaria expanding?

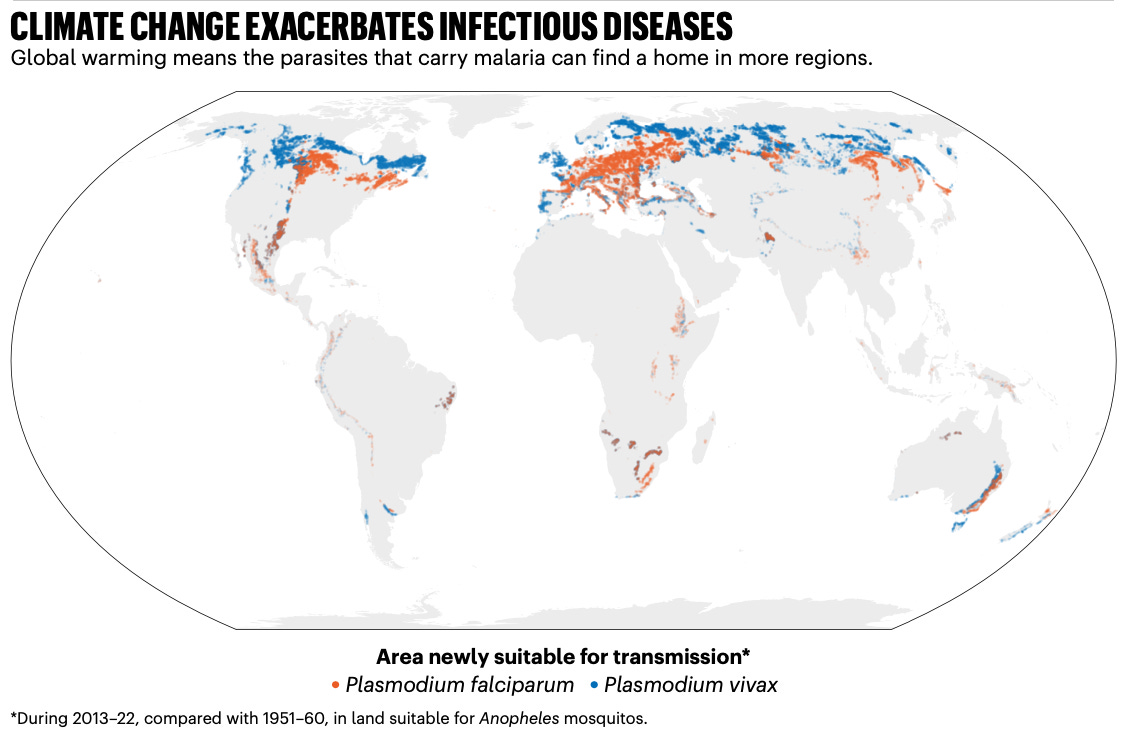

The second Nature article also claims that “Global warming means infectious diseases are expanding into newer regions.” The map below supposedly corroborates this assertion by showing an expansion of global land area suitable for malaria transmission based on “precipitation, humidity, and temperature levels in which malaria could spread for at least one month per year, on average, over a decade.”

The messaging and the chart certainly seem to indicate that the incidence of malaria is increasing. But again, this is not exactly true. In fact, many of the highlighted regions from the map in the Nature article used to have a prevalence of malaria but are now malaria-free due to the use of insecticides, the drainage of swampland, and improvements in housing conditions:

The data from the above study ends in the early part of the 21st century, but according to the most recent World Malaria Report published by the World Health Organization, there are not significant numbers of malaria cases in the regions identified in the Nature article map, and the overall incidence of malaria worldwide (and death rates from malaria) continues its long term decline:

The World Malaria Report also discusses future projections, indicating that the incidence of malaria will likely continue to decline despite climate change (emphasis added):

Under the “middle-of-the-road” climate scenario (SSP2), the analysis suggested that, under current levels of intervention coverage, combined with changing environmental and socioeconomic conditions, malaria incidence is likely to decrease (Fig. 10.5), even if malaria cases increase slightly because of population growth. If current interventions are scaled up to high levels of coverage and the predicted changes in environmental and socioeconomic conditions are maintained, the analysis suggests the potential for substantial reductions in malaria incidence. The addition of novel interventions (e.g., highly efficacious vaccines and monoclonal antibodies) is likely to increase the impact of interventions further, even as the climate changes.

So the claim that infectious diseases like malaria are expanding to newer regions seems to be without any merit.

Is hunger increasing?

Finally, the second Nature article claims that, “As the world heats up, more people are losing access to safe and nutritious food.”

Over the long term, it is simply not the case that warming has coincided with people losing access to food. This is partially because yields from major crops have been increasing dramatically over the modern period of global warming, which has translated into an increase in the food calories available per person:

The Global Hunger Index, designed to comprehensively measure and track hunger, shows a long-term decrease in hunger in all global regions:

It is true that the long-term decline in undernourishment has stagnated recently, and there has even been an uptick over the past several years. But fluctuations on timescales of several years are not likely to represent climate change signals, which evolve much more slowly. Rather, these fluctuations can be much better explained by direct influences of COVID-19, food price spikes from the Russia-Ukraine war, and other harms to food production in sub-Saharan Africa due to conflicts.

So how does the Nature article arrive at its claim? The authors cite a model from a 2022 study that estimated that “127 million more people will have experienced moderate-to-severe food insecurity as a result of climate change in 2021 compared with a scenario without global warming.” That model used a regression analysis where the effects of short-term weather variability were treated as having the same effect as long-term climate change (e.g., they do not allow for any adaptation to climate change). That assumption is, of course, questionable, but there’s an even bigger problem with this analysis: the calculated effects of climate change are simply small relative to variations in technology and economic development.

This can be appreciated when we look more closely at the results. The left column below is the actual observed incidence of moderate to severe food insecurity, and the right column is what they estimate would have been the incidence without climate change:

Notice the large differences between the regions (e.g., a 36.7 percent difference between Africa and Europe) and the comparatively small effect of climate change (under three percent for all regions). This tells us that economic and societal differences are much larger determinants of food insecurity than changes in climate. This is, of course, the reason why long-term economic and technological development can cause the overall incidence of hunger to decrease over time despite climate change. That’s important because many of the same systems driving climate change are responsible for the long-term decrease in hunger.

Here’s how this point was put in a recent similar analysis:

Our estimates (counterfactual scenario) should not be interpreted as the effect of a world without fossil fuels on global agriculture production. Agriculture has benefitted tremendously from agricultural research and carbon-intensive inputs that would not have been as available without fossil fuels. The counterfactual in our study only removes the effect that fossil fuels and other anthropogenic influences have on the climate system.

So are “more people losing access to safe and healthy food?” Not on climate timescales, no. This can only be interpreted as true in an obscurantist way where “more” is meant to mean “more” relative to a hypothetical counterfactual world where you get to keep carbon-intensive infrastructure but jettison climate change. It is not true if “more” is interpreted to mean more than in decades past.

Summary

The most generous interpretation I can give of these articles is that all four claims leave out important context—most relevantly, the phenomena they are discussing are all trending in good directions. The stubborn insistence on finding the negative climate impact in the otherwise positive story diverts attention away from studying and publicizing the reasons for success, and also misleadingly paints current systems as less attractive than they are. Climate change is a major concern, particularly because it will not stop until global human-caused CO2 emissions reach net zero, and we are very far away from that. But the full-scale rapid reorganization of the world's energy and agricultural economies should not be sold under false pretenses.

Less generously, I’d say the articles are playing to the tastes of their audiences. It also seems as though Nature and the underlying report from the Lancet are attempting to use their authority as trusted scientific institutions to foster more action on CO2 emissions reductions. The irony, however, is that when an institution becomes activist, it is much more prone to spinning the data, which then undermines the very authority it is attempting to leverage. Society needs neutral scientific institutions that it can trust to give a foundational view of reality as free of spin as possible.

We know that we are losing many media outlets to overt activism and audience capture, but it is a shame that scientific publications like Nature seem to be following suit.

Patrick T. Brown is a Ph.D. climate scientist, co-director of the Climate and Energy Team at The Breakthrough Institute, and adjunct faculty at Johns Hopkins University.