Editor's note: This is the first of two reflections on the recent German election in The Liberal Patriot. Today's piece from Claire Ainsley examines what the election results mean for Democrats and center-left parties globally and next Monday's piece from Henry Olsen examines the implications for national populists.

Last month’s federal election in Germany, which took place at a moment of significant global tension, has attracted international attention. What the new German government, under the leadership of Chancellor Frederich Merz, says and does now on Ukraine, and on the changing relationship between the United States and its oldest allies, will have immediate and long-term repercussions for the global geopolitical picture. Merz’s early comments that Europe will have to have “independence” from the U.S. as the Trump administration increasingly abandons its historic allies, and his willingness to loosen Germany’s “debt brake” to fund ramping up defense spending, have made headlines over the world.

The election was also significant because of the electoral swing from left to right, a result that has important insights for the global center-left, including U.S. Democrats, at this critical juncture as they continue to suffer declines with working-class voters.

The big story coming out of the German election was the downfall of the center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD) led government, the revival of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), and rise of the right-wing challenger party Alternative for Germany (AfD). Prior to the election, German voters had grown weary of the inertia of the “traffic-light” coalition (a reference to the colors of the three coalition parties), in which the SPD governed with the Greens and the free market-oriented Free Democratic Party (FDP) at the helm of the finance ministry to make the parliamentary numbers work. These coalition partners ultimately could not agree on the direction of fiscal policy and consequently suffered greatly with the electorate. SPD Chancellor Olaf Scholz called time on the coalition early, firing the finance minister in December and triggering a confidence vote in his own leadership, which he failed. This led to an early federal election in February, in which the CDU’s Merz became the new chancellor. Although coalition talks are still ongoing, the third-place SPD is likely to remain in government as the junior partner in a new coalition.

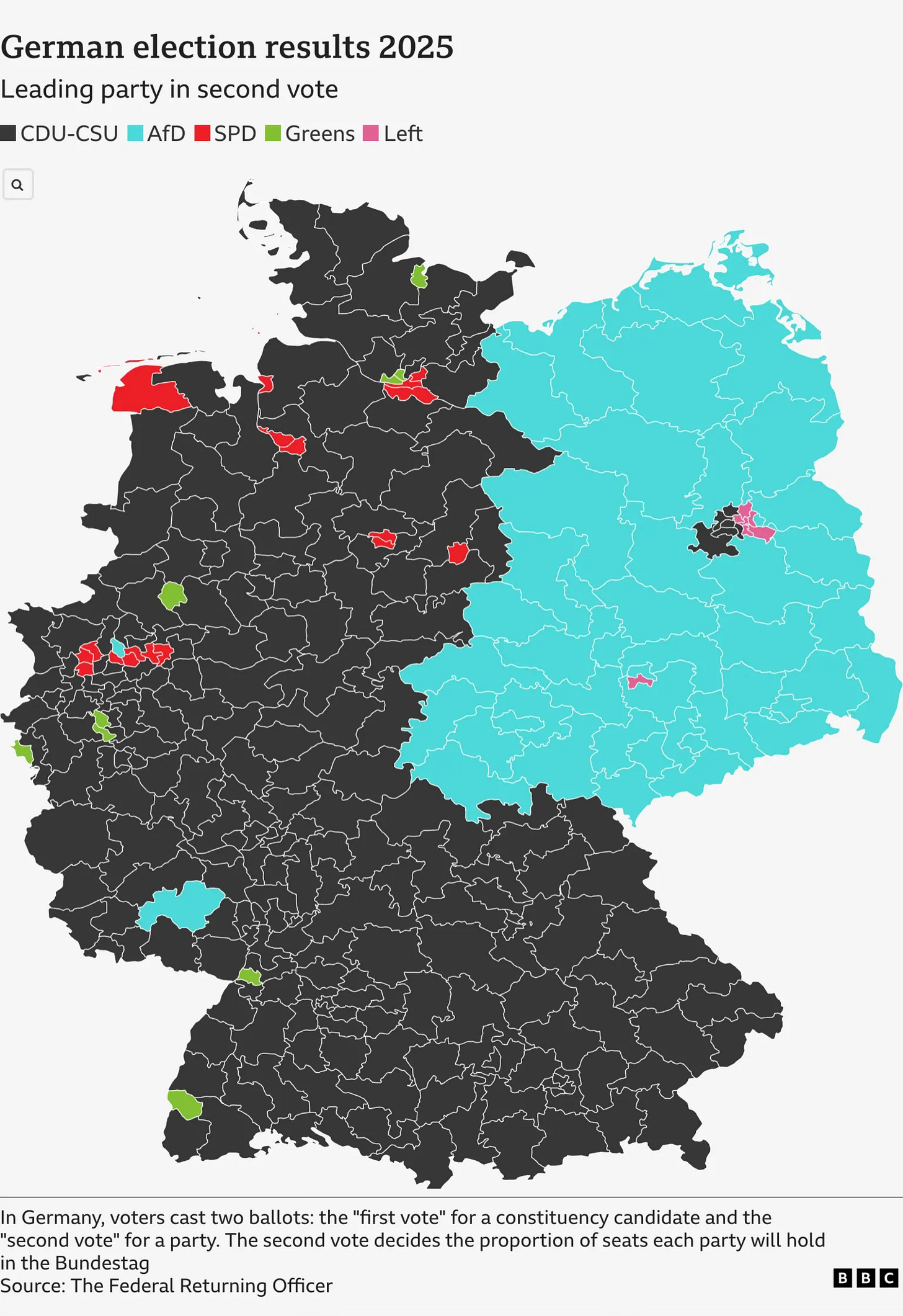

Meanwhile, the AfD surged, finishing in second with double its previous vote share. The party has grabbed more than its share of international headlines for its hard-right politics. They support deporting migrants in mass numbers, quitting the European Union, and resuming the purchase of Russian energy. On the February ballot, the AfD increased its national vote share from 10 to 20 percent and dominated in East Germany where it had already been successful in recent state elections. As seen in the chart below, the geographic disparity between East and West in the politics of the recent vote is stark, even as Germany is thought to be admired the world over for reconciling its past and reunifying the two regions in one of the most successful political projects of recent times.

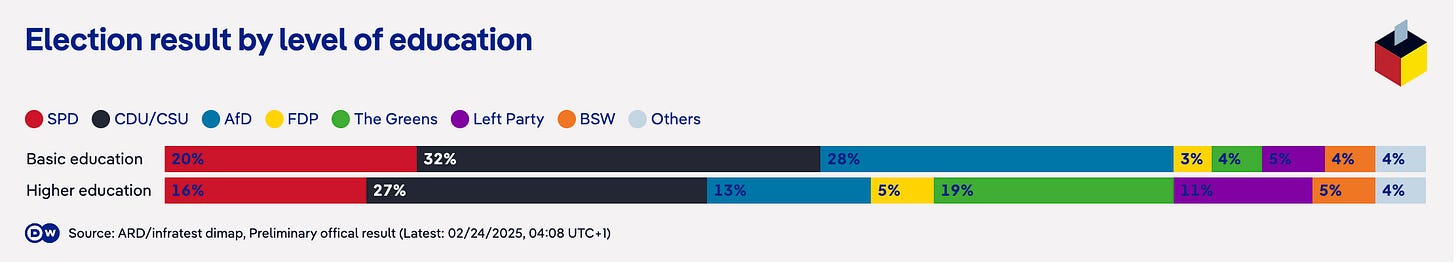

By contrast, the SPD dropped 9.3 percent compared to its 2021 vote, with a historic low vote share of just 16.3 percent. Bear in mind that the SPD polled more than 40 percent of the vote in its heyday under centrist leader Gerhard Schroeder in the 1990s. But the story is not as simple as the SPD losing its working-class vote to the far-right in this election. Most of the SPD’s lost support went to the center-right CDU party, while most of the AfD’s new support came from non-voters. (The AfD also took more votes from each of the CDU and the FDP than from the SPD.) While the SPD’s electoral base still disproportionately comprises non-higher-educated voters over those who have been to university, their base has been shrinking between pressure from the right-wing among its non-college voters and pressure from the left-wing and Greens among its higher-educated voters. If these trends continue, they will make it difficult for the SPD to achieve first place in future elections.

The SPD is battling it out with the right for non-college voters, the bulk of the German electorate. The left and the Greens don’t really compete among non-graduates, as their electoral base is derived almost entirely from the higher educated. The other challenge for the SPD is attracting younger and middle-aged groups. Both the SPD and the CDU rely on the over-50’s—remarkably, the AfD was the most popular party in this election among 30–44 year-olds. And younger voters (under 30) tended to opt for the AfD or the parties to the SPD’s left.

Keep in mind that the working-class shift away from the center-left in Germany does not perfectly reflect what has occurred with Democrats in the United States. The German electoral system offers multiple options for voters, thus splitting working-class support among different parties. Likewise, the SPD’s voter base is historically older than that of the Democrats (or the Labour Party in the U.K.). And, more so than U.S. Republicans, the non-traditional AfD has attracted many younger and middle-aged voters displeased with the status quo.

The center-left’s loss of working-class voters in Germany is not for lack of trying. Unlike the presidential campaign of Kamala Harris, which mainly focused on attracting the support of white college-educated voters, SPD’s Scholz deliberately targeted working-class Germans. In both of the SPD’s federal election campaigns in 2021 and 2025, Scholz ran on bridging social divides on wages and pensions, showing respect for working-class communities, and standing up for the “millions not the millionaires.” In fact, the SPD’s worker-centric campaign in 2021 provided a source of inspiration for Keir Starmer’s Labour Party, then in the opposition and looking for ways to reconnect with its own lost working-class base.

But in Germany, as in the U.S., these efforts have increasingly come up short. It is only possible for major center-left parties like the SPD, the U.S. Democrats, and the British Labour Party to win legislative majorities in their respective countries if they are competitive among today’s working-class (non-college) voters. There isn’t a future for any of them in appealing primarily to university graduates and urban voters.

The SPD lost the support of ordinary Germans just a few months into the coalition’s previous term of office. A series of incumbency challenges gripped the government, including soaring energy prices, exacerbated by the country’s pre-Ukraine war dependence on Russian gas. While Germany has recovered from its initial exposure to the energy crisis—in part because it replaced Russian energy with U.S. liquid natural gas and because inflation has returned to more normal levels—its longstanding economic problems like weak productivity and high export reliance have continued to plague its post-Covid economy. The failure of the politically-stretched coalition to agree to reform the German “debt brake”—which the new chancellor, Merz, was able to announce within days of the election—meant that the government could not settle on a plan to finance its spending and service its debt.

Merz has justified his revised view on the debt brake based on the new call to increase defense spending, echoed across Europe, which is due partly to the U.S. position and partly to new and escalating threats in a multipolar world. Yet, the previous coalition government had justified the push to reform the debt brake—which was ultimately unsuccessful—on the basis that it sought to finance ambitious new plans for energy transition. The plans proved controversial with many voters who felt the costs of climate policies were being pushed onto households, and this contributed to the loss of support for the SPD and the Greens. The AfD capitalized on the backlash, but center-left parties elsewhere don’t need a right-wing challenger party in their midst to reflect on the obvious conclusion that working-class voters do not want to be forced down a rapid energy transition route if they believe they are going to foot the bill.

The German experience is the real-world example of polling that The Liberal Patriot and PPI have previously published showing that voters are generally pragmatic rather than ideological on the climate—they care about the environment but don’t want to take a hardline approach to ending fossil fuels if it means the costs fall on consumers.

But the top issue for German voters in the election turned out to be immigration, not just for AfD or CDU supporters, but for every party supporter outside of those backing more left-wing parties or the Greens.

Scholz had hardened the government’s position on immigration more recently, even abruptly closing borders last year, but voters saw it as too little, too late. In one pre-election poll, fully 80 percent said that immigration had been too high in the last decade, with 54 percent saying “much too high.” This offers an important lesson for center-left parties elsewhere: immigration isn’t just a tricky issue to manage politically, but a central concern that must be prioritized.

The SPD is likely to stay in government for now as the junior partners in a more cohesive coalition, albeit with a lost chancellery and diminished parliamentary power. The CDU has so far kept to its word that it will not cooperate with the far-right AfD, even though it relied on their votes just before the poll to get through new immigration measures.

But Merz knows the center is on borrowed time. If a center-right led government cannot satisfy the German demand for change, voters may well conclude that a more radical shift is needed. The CDU, together with the SPD, have a chance to show that the political center can be a dynamic force for change by prioritizing the needs and concerns of working-class Germans in a changing world. It may be their last chance.

Claire Ainsley is the Director of the Center-Left Renewal Project at the Progressive Policy Institute, and former Executive Director of Policy to U.K. Labour leader Keir Starmer 2020-22.

The German lesson for Democrats is to keep a tame conservative party around that will implement center-left policies even if they win. The FDP was punished for collaboration and is excluded from the new Bundestag. However, that ship has sailed in the US. It has sailed in the UK too where the landslide victory of Starmer Labour got less votes than the landslide defeat of Corbyn Labour. UK Conservatives simply stayed home or voted Reform. We will see what happens in France and Austria where firewall government is in effect. Democrats seem to be following the Romanian approach of using the courts to nullify elections. That may work but is extremely destabilizing. The previous Democratic strategy of boosting "extreme" candidates in the Republican primaries has already failed.

The results of the German election and the more recent decision of Germany's mainstream political politics to abandon economic austerity are signs of support for strengthening the European Union, doubling down on opposing Putin's revanchism and advancing clean energy development. The German election and Macron's renewed popularity points to a longer term decoupling of Europe's economic and security policies from the United States as we abandon our role as leader of the free world.