What Americans Think About the “Language Wars”

People generally want to be inclusive, but many are wary of top-down dictates on what constitutes “correct” thinking.

Some of the most interesting conversations taking place in Western democracies today are about language—what is okay to say, what is not, what is outdated, what is in vogue. Language is always changing, and there are usually good reasons for this. As our societies have evolved morally and begun to prioritize inclusion and tolerance, we’ve sought to shun the use of slurs against minority populations and adopt the terms they desire to be called. After all, most people likely want to be respectful of others and have no desire to actively offend them.

But fostering widespread acceptance of new terms and phrases can be tricky. As linguist and New York Times columnist John McWhorter has written, part of the trouble with the “latest thinking” about certain terms is that it tends to be based on “an attractive but shaky idea that language channels thought: Change how people say things and you change how they think about things and then the world changes. That’s not how it works, though. Good intentions frequently don’t translate into efficacy.”

Moreover, this kind of thinking often isn’t based on input from the groups at the center of those debates—or, at least, from a representative sample of them. This is what leads to terms like “Latinx,” which represents an attempt by left-leaning English-speakers to change a Spanish descriptor (“Latino”) for the putative purpose of making it more inclusive.1 But it was never clear that actual Hispanic or Latino Americans were pushing for this change. In fact, according to multiple polls, only around 2–4 percent of them use the term, and a sizable share even find it offensive.

This is far from the only example. The term BIPOC (black, indigenous, people of color) came and went in the blink of an eye, likely due in part to the fact that many black and indigenous people didn’t use it. Disagreement over terms like “pregnant people” in lieu of “pregnant women” have seemed to pit the modern-day concept of “gender identity” against the female experience. One debate that has gotten less attention has been about the term “homeless people,” which some have tried replacing with more innocuous-sounding phrases like “unhoused people” or “people experiencing homelessness,” despite the fact that this change has been tried before and as some housing advocates have argued that removing the stigma surrounding homelessness may actually be ill-advised.

Clearly, American culture has become more engrossed in these debates over the past decade or so.2 The problem is that they have mostly taken place in the upper echelons of society—in academia, activist circles, social media platforms, DEI seminars, and the like. Meanwhile, it’s less common to hear what ordinary Americans, who likely have far less time to dedicate to these meta conversations, think.

So, what does the rest of the country think about all this?

Luckily, The New York Times set out to answer this question a couple years ago, just as the country was beginning to emerge on the other side of the “great awokening.” In conjunction with the polling outfit Morning Consult, the Times conducted a national survey that gauged which words Americans still viewed as acceptable versus which they thought should be left behind.3 The results were quite enlightening.

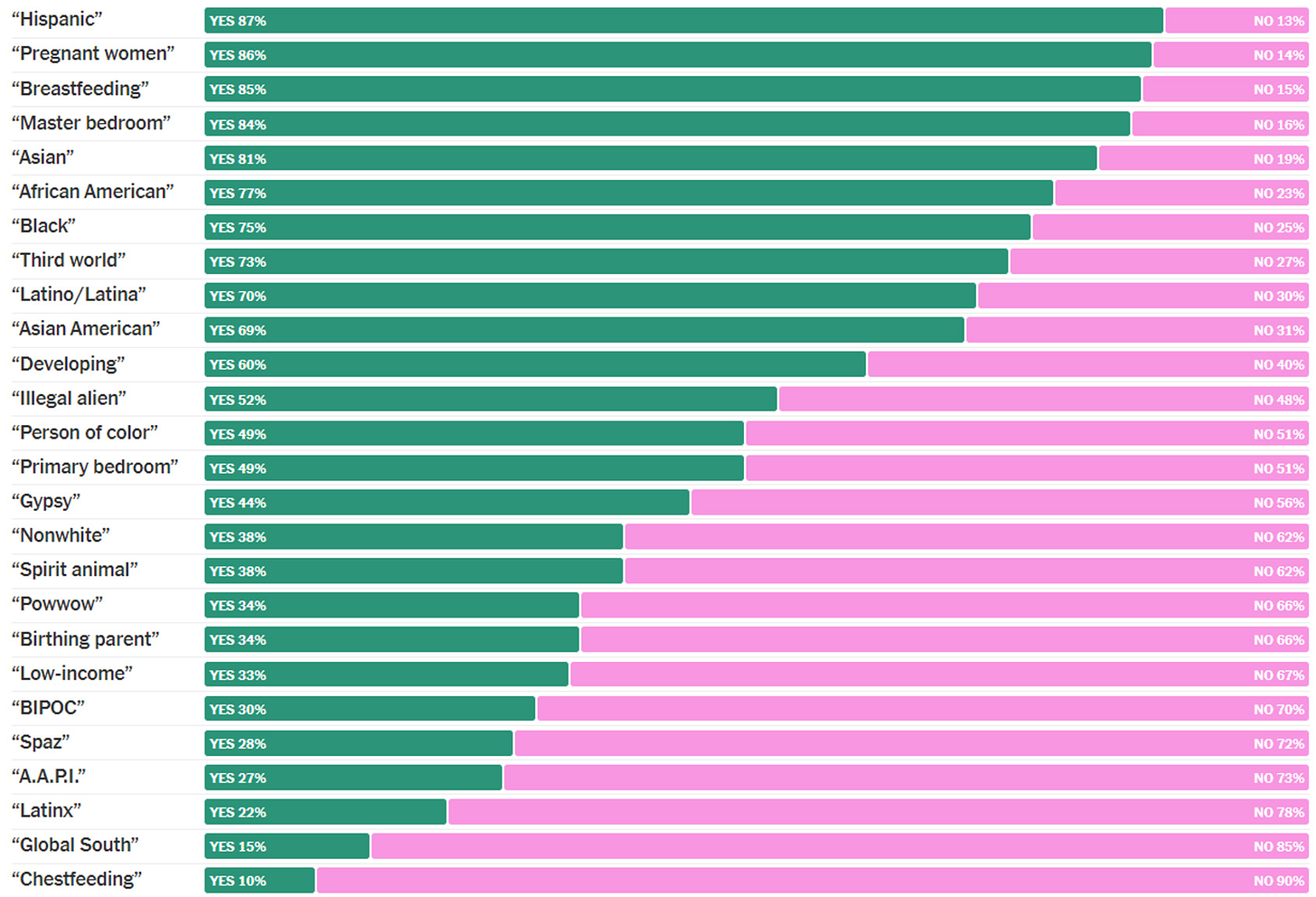

First, here’s a short rundown of some words that Americans say they would (“Yes”) or would not (“No”) use:

As we see, many terms that have been part of the mainstream lexicon for years, if not decades, are still commonly used today. When it comes to racial or ethnic identity, for example, most Americans continue to use the widely accepted “Hispanic” and “Latino” rather than “Latinx.”4 Similarly, they are likelier to say “Asian” or “Asian American” instead of “AAPI” (Asian American and Pacific-Islander). Interestingly, both “black” and “African American” continue to be accepted terms. However, black Americans, alongside Republicans, are likelier to prefer the former, while Democratic groups are likelier to say “African American.”

Observing that many of these newer terms around race and ethnicity have failed to catch on, McWhorter wrote, “A lot of these racial name changes tend to come from above or outside a community rather than within it.” He added, “I don’t know the histories of ‘A.A.P.I.’ or ‘BIPOC’ in detail, but none of these terms emerged from the folk, as it were. They are enlightened suggestions from the educated and the highly activist. It isn’t an accident that I learned of all of them on Columbia’s campus.”

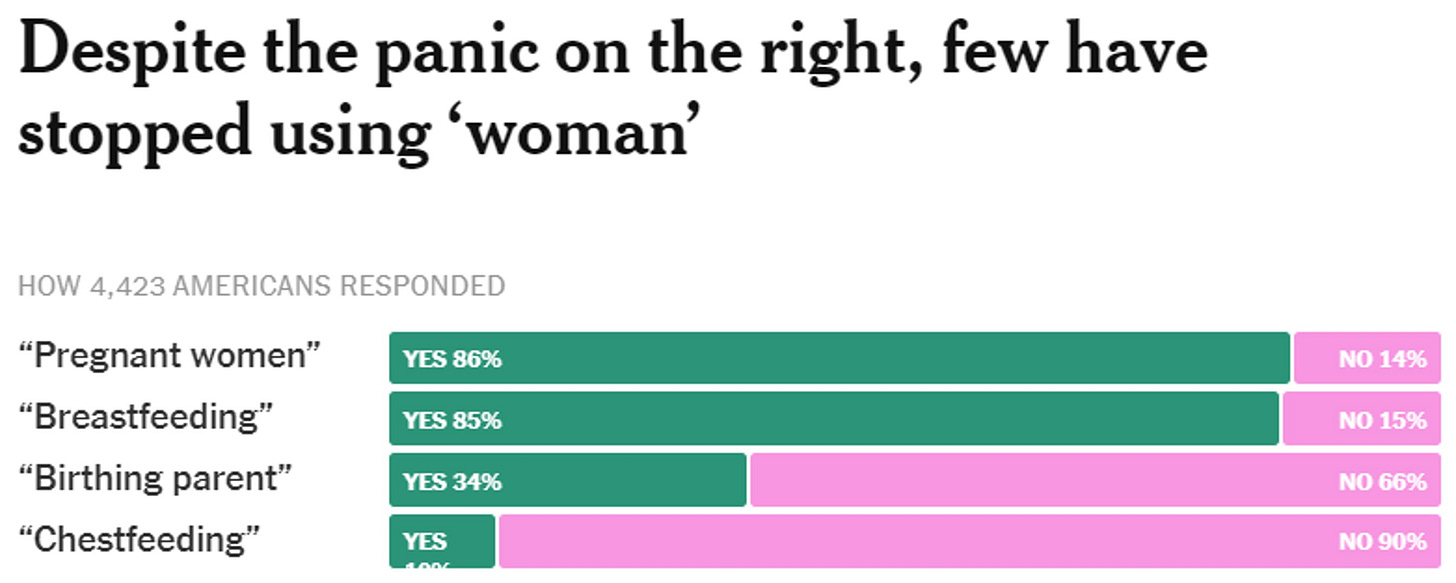

Additionally, on questions about sex and gender, Americans continue to embrace conventional terms like “pregnant women” (over “pregnant people” or “birthing people”) and “breastfeeding” (over “chestfeeding”).

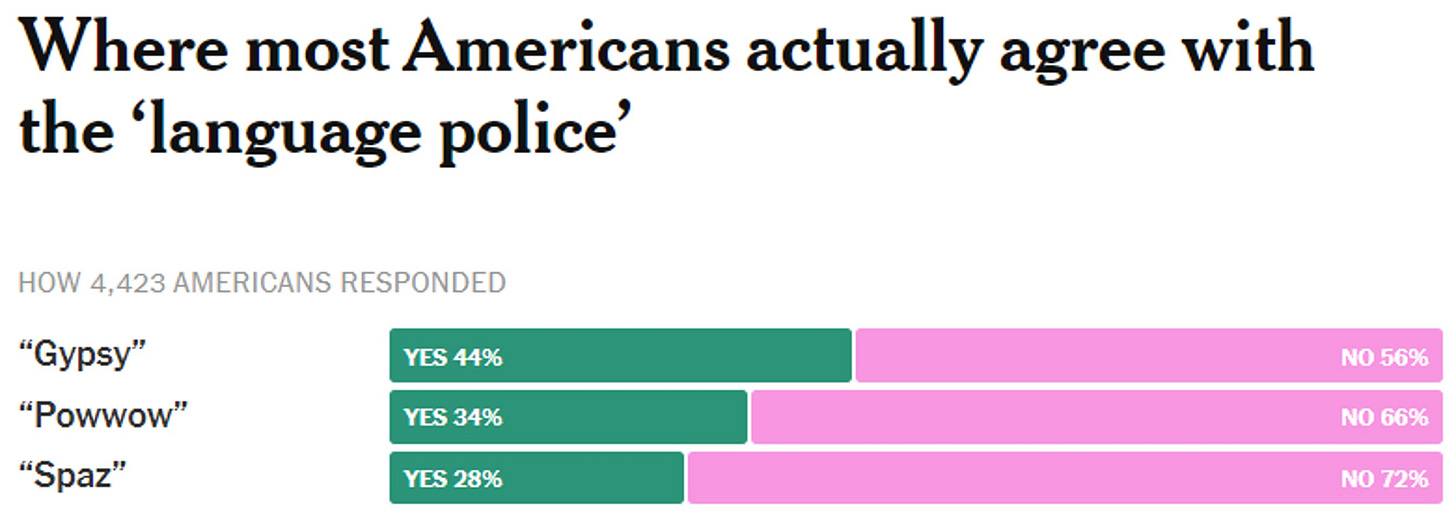

There are, though, some terms that most people seem to agree are outdated or needlessly offensive. This notably includes “spaz,” which is based on “spastic diplegia,” a medical condition that causes motor impairments in the arms or legs. Spaz has typically been used as an insult to describe someone who is clumsy or prone to losing control. Consternation over this word came up a couple of years back in a debate over song lyrics from artists like Beyoncé and Lizzo.

So the big picture is fairly clear: while most Americans are open to discarding some outdated terms, especially those thought to be slurs, they generally have not adopted newer changes pushed predominantly by activists and academics. Part of this may be a widespread aversion to “political correctness,” which has made some people feel anxious about using the wrong word and risking backlash for doing so. Another large-scale survey found that an astounding 80 percent of Americans agreed that “political correctness is a problem in our country.” In one of the study’s focus groups, a 40-year-old American Indian man put it thusly:

It seems like every day you wake up something has changed…Do you say Jew? Or Jewish? Is it a black guy? African-American?…You are on your toes because you never know what to say. So political correctness in that sense is scary.

Indeed, there are a few reasons why some people could be frustrated by these language changes. First, it may feel as though the terrain is constantly moving under their feet, making it difficult to keep up—that what was thought to be enlightened language five minutes ago, such as Latinx or BIPOC, is now dated or unacceptable.5 One Times columnist reflecting on the survey results described these difficulties:, “I think this gets at part of the problem with all of this language policing: It can be hard to keep up, even when it is, well, literally your job to keep up. And who makes the rules, anyway?” In this way, efforts at creating more inclusive language can ironically sometimes become exclusionary when the vast majority of the population doesn’t know what is or isn’t “acceptable” and feels that the lines keep shifting.

Second, there is some perception that these changes are often being declared almost by fiat by people who work in institutions that have outsized influence over shaping the culture—academia, media, activist spaces—even though that segment of the population is relatively small and their views on cultural matters tend to be unrepresentative of the rest of the country’s. It was notable, for example, that another Times columnist reacting to these answers seemed genuinely surprised that big majorities of Americans clearly preferred the term “pregnant women” and that they had no qualms about referring to a home’s “master bedroom.”6

Finally, no one likes a hall monitor, or a feeling that they’re constantly being watched and judged by others, especially if those others sit on a higher sociocultural rung, waiting to pounce when someone commits a language faux pas. Activists who are sincerely committed to social change might exhibit some grace in these conversations if they hope to convince people to consider their beliefs and ideas.

It’s possible this seeming tug-of-war between those promoting language changes and the rest of society will continue on for some time. But, McWhorter noted, it may also be that the trajectory of this debate ultimately breaks in favor of those who sit atop America’s cultural institutions:

…the people most committed to this kind of change tend to be more educated, given to thinking about groups and actions in the abstract—as opposed to those who may be too busy living an existence to be concerned about the labels for it. In any case, where we are headed is that a certain sliver of our population will control a rich jargon of prescribed terms, of little import to most people.

Language in healthy societies inevitably evolves over time. The important question for us to consider is whether these changes are both necessary and built with community and stakeholder input—or whether they are simply being pushed by well-meaning busybodies who don’t actually speak for the communities in question.

Editor’s note: a version of this piece first appeared on the author’s personal Substack earlier this year.

For those who do not speak Spanish, adjectives describing a man end with an “o” while those describing a woman end with an “a.” The argument from those advocating for the adoption of “Latinx” (or its Spanish-language equivalent, “Latine”) is that defaulting to “Latino” supports a male-dominant view of Hispanic ethnicity, and limiting the terms to “Latino” and “Latina” reinforces a gender binary that excludes people who do not identify as a man or a woman.

See, for example, the numerous efforts by universities to roll out new language guidance—and the backlash to some of them.

You can take the interactive quiz to see how you match up against the rest of the country.

As do, unsurprisingly, huge majorities of Hispanic Americans.

A personal example that comes to mind was when I heard an older neighbor in the small Missouri town where I went to college refer to a “colored person.” It’s very possible he meant it in a disparaging manner. But it’s also possible that he was searching for what he thought was the enlightened term—“person of color”—but confused it with a more outdated term that sounded very similar (and one that notably remains in the title of one of the nation’s preeminent civil rights organizations).

McWhorter has pointed out that this term is often incorrectly deemed problematic based on errant assumptions about its historical origin.

History lesson:

In the 19th century, people with mental disabilities were called cretins, imbeciles, and idiots. By the early 20th century, this became a formal classification: idiots, whose mental age never exceeds that of a typical two-year-old; imbeciles, whose mental age never exceeds that of a seven-year-old; and morons, whose mental age never exceeds that of a twelve-year-old. Cretinism became a specific term for congenital hypothyroidism, leading to a syndrome that includes cognitive disability.

Of course, these terms became insults in popular vernacular for anyone who does or says something stupid. Bugs Bunny was fond of saying of inept adversaries, "What a maroon!" That's clearly not a reference to escaped Haitian slaves, but a variation on "moron." More recently, Ren Hoek of Ren & Stimpy had frequent outbursts at Stimpy the Cat, calling him an "eediot."

Because some well-meaning people thought they could end the hurt behind the use of these words by banning the words, they were replaced with the concept of developmental rates. The accepted terminology became "mental retardation" to reflect that these persons were just, as the euphemism goes, "slow." The truth is that many people with such disabilities are not just slow to develop intellectually, but incapable of developing beyond certain limitations.

"Retarded" was the politically correct term for such people in the mid-20th century. But of course, "retarded" and "retard" entered the vernacular as insults. This spawned an ongoing struggle to find an acceptable term for cognitive and intellectual disabilities: developmentally disabled, developmentally challenged, developmentally delayed (note that "delayed" is a direct synonym of "retarded"), mentally challenged, and so on.

The issue isn't the words. If you want to put someone down by calling them profoundly, inherently stupid, you will use whatever term people currently used for the developmentally disabled - even "special."

The point of controlling the words is to attempt to control people's ability to think, as with Orwellian Newspeak. If you can relegate the population to a constant scramble to keep up with the right words on pain of ostracism, you can keep them from questioning the control you have over them - even as you expand and extend that control to all aspects of their lives. In effect, you reduce them, to (in the words of MAD Magazine) a gang of idiots.

The problem with this approach is that there is no mass public input. Before referring to moms as birthing people, shouldn't someone ask moms if this is okay with them? And, then you have people like my husband who works 12 to 16 hours a day. He depends on me to keep him informed of IMPORTANT matters. He has no time or energy for trivial word games. He's in the beginning stages of building up a business, so he has dedicated his time to that pursuit. Now, let's say one of these hall monitors comes in to his business and he unknowingly uses a word he's always used. In some circles, that is cause to destroy him, his business, his family, and his good-hearted nature. Why? What good does that do? Lots of people will lose their job because he can barely hold his eyes open long enough to even remember what day it is. It's ridiculous and people who do this to others are the ones who should be shunned. They obviously have too much time on their hands.