U.S. Foreign Policy’s Humpty Dumpty Challenge

After a period of fragmentation in the politics of national security, an opening appears to put the pieces back together again by building new coalitions at home.

In the last few election cycles, foreign policy hasn’t featured as prominently in America’s political debates as much as it did at the start of the 2000s.

Americans have been more sharply focused on challenges at home like the economy, jobs, health care, education, and most recently the COVID-19 pandemic. This stands in sharp contrast to the immediate post-9/11 period and the debates of the Iraq war that really drove politics from 2002 to 2006.

During the past decade, the traditional foreign policy camps like the neo-conservatives and liberal internationalists have lacked the coherence and political relevance they once did, for a number of reasons. First, the poor track record of results in the world by both Republican and Democratic administrations, underscored by America’s recent defeat in Afghanistan, led to a crisis of credibility for those camps.

Also, the backlash against globalization and the growing economic concerns at home, driven a sense that America’s economic model wasn’t delivering for its own people in comparison to competing models in Asia and Europe, added to the decline in the traditional foreign policy camps. This created an opening for the rise of divisive, populist nationalism on the right and left.

Lastly, a number of new voices in U.S. politics have risen to challenge the more traditional foreign policy camps. These different voices tend to be more reactive and critical to existing policies, but they are often less clear about practical policy alternatives and sometimes use divisive tactics that put a limit on their ability to build support.

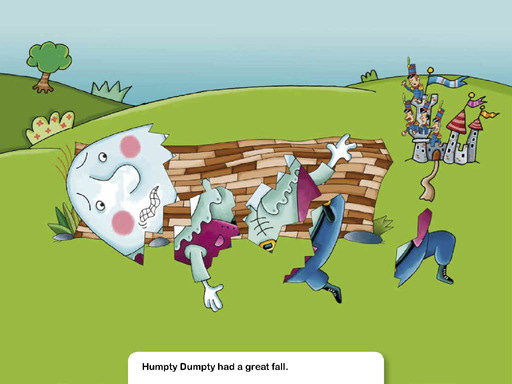

This fragmentation in the politics of U.S. foreign policy is what I sometimes call the Humpty Dumpty challenge, after the nursey rhyme in which Humpty Dumpty falls from a wall and splinters in many pieces, ending with: “All the king’s horses and all the king’s men/Couldn’t put Humpty together again.”

The past ten years in the politics of U.S. foreign policy has seen new political forces splintering a national consensus on foreign policy and advancing a narrower agenda representing smaller groups that sometimes punch far above their electoral weight and actual power due to their stridency in social media.

A recent study by the Pew Research Center offers a more detailed and textured segmentation and analysis of the different political camps inside both the Democratic and Republican parties.

This typology digs deeper than just the surface-level Red versus Blue divides and defines four camps inside the two parties, as well as ninth category, “Stressed Sideliners.”

The study is worth a look on all issues, including national security. This research offers some important insights, including the lack of popular resonance of the restraint and retrenchment foreign policy camp, as Peter Juul has also noted in analyzing other data sets.

The Pew Research Center study offers a wealth of data on how these different segments view a number of key national security questions, including defense spending. On the size of the U.S. military, for example, a strong majority of Americans (68 percent) want to either keep it as is (43 percent) or increase it a little (25 percent). Only the progressive left, which represents 6 percent of the overall population, has a majority of its members wanting to see the size of the U.S. military decreased – showing what an outlier this group is from the mainstream.

There are other ways to segment Americans on their foreign policy views – this study by the Center for American Progress in 2019 defined four different categories of voters.

The bigger point in all of this: the politics of U.S. foreign policy is very much in flux, like many other issues in U.S. politics these days. That creates an opening for a new narrative.

U.S. presidents have a strong ability to shape the narrative about U.S. foreign policy, but the Biden administration has not yet advanced a clear sense of priorities that can win over a broad swath of Americans. It instead has relied on slogans like “a foreign policy for the middle class” without building clear policies to define what that means in practice. The Biden administration’s foreign policy focus has been a technocratic managerialism. To date, Biden’s foreign policy narrative is less conceptual and lacks a clear story.

This scenario presents an opportunity for foreign policy voices interested in building new coalitions in America, rather than continuing the fragmentation that has occurred in the past decade. A new inclusive nationalism at home is the best first step for building a more stable political foundation for U.S. foreign policy engagement, one that emphasizes the core principles of freedom, security, and prosperity.

It will take some time for new camps to form and coalesce on U.S. foreign policy, but a careful look at the political appetite of the American public finds a pragmatic pathway for a more balanced foreign policy approach that seeks to build coalitions at home.