Union Voters Could Be Decisive in 2024

Biden’s chances in the Midwest may depend on how this longtime Democratic constituency votes.

As the 2024 presidential election draws ever closer, political pundits, analysts, and practitioners have been closely examining each of the two major parties’ coalitions—which voting blocs may be the most the most influential next fall, where each party has an advantage, and where each needs to shore up support. Many have written on the GOP’s enduring problems with young voters and college-educated suburbanites. Others (including me) have routinely highlighted the Democrats’ lingering issues with rural and non-college-educated voters as well as their growing attrition among Hispanic Americans.

However, there is one group of voters who possess significant influence in key swing states and whom politicos and the media tend to ignore: union households. Historically, Americans who belong to a union (as well as others in their household) have been a formidable force in electoral politics. These voters often cast their ballots with worker-focused issues in mind, such as fair wages, good benefits, and the right to practice collective bargaining.

The party that for decades took a strong stand on workers’ issues—the Democrats—has tended to perform very well with these voters. According to the AP VoteCast survey, in 2020, Joe Biden won them over Donald Trump nationally by 14 points while only winning non-union-household voters by two points. This was in line with longer-term trends showing Democratic presidential nominees often winning union-affiliated voters by double digits but the remainder of the electorate often being up for grabs.

We see this borne out at the state level, too. In the six presidential elections that took place from 1992 to 2012, 15 of the 21 states whose union membership rate was higher than the national average (13.5 percent) voted for the Democratic nominee in all of them; another two states did so in four of the six. By contrast, among the 20 states with the lowest union membership rates, none voted for the Democrat in every election, and just one (New Mexico) backed the party’s nominee a majority of the time.

Unions themselves have also long been among the biggest sources of money and organizing power for Democrats. In the 2020 election, for example, labor groups contributed a whopping $27.5 million to Biden’s campaign and other entities that supported him, while Trump earned just $360,000 from similar groups. Unions are also traditionally some of the biggest donors to the Democratic Party’s committees and PACs responsible for electing downballot candidates.

However, despite their historic power and influence in politics, union affiliation in the United States has also declined for more than half a century. Some of this has been the result of macro-level factors such as globalization, outsourcing, and automation. It has also partly been due to politics: when voters swept Republicans into power in statehouses across the country following the 2010 midterm elections, for instance, the new class of legislators passed a slew of laws targeting unions, including in states with strong union traditions like Michigan and Wisconsin.

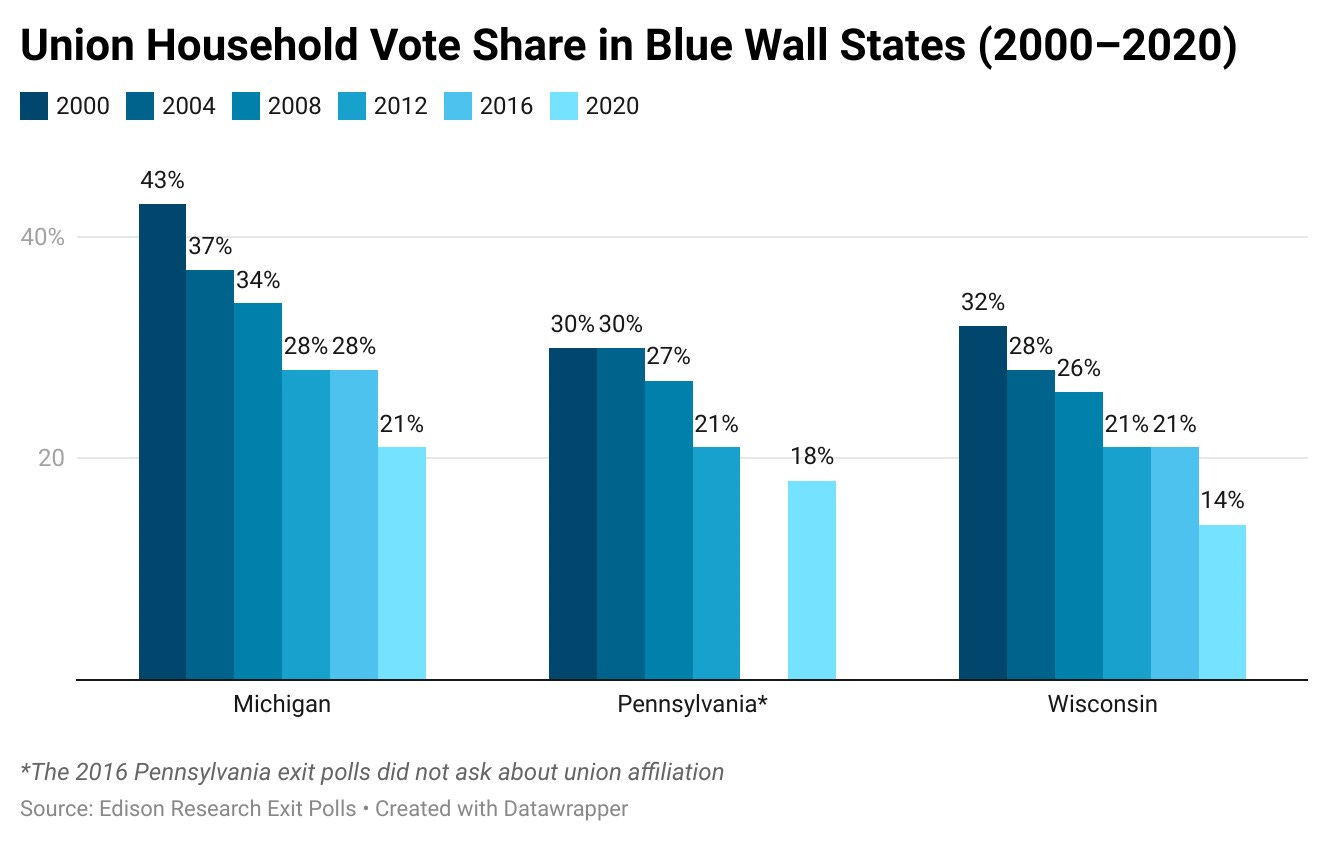

These trends have all weakened union power, not just in the workplace but also in elections—especially in the Democrats’ “Blue Wall” states. According to national exit polls—which are often flawed but also the only source of historical data we have tracking union households’ voting trends—this group’s share of the electorate in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin has shrunk in tandem with the decline in union membership, diluting the impact of their support for Democrats.

At the same time, there is evidence of movement toward Republicans among at least some of these voters. In 2016, Trump won 42 percent of union households nationally, more than any GOP presidential nominee had earned since at least 1996. Meanwhile, Clinton won a bare majority (51 percent), the worst performance for any Democratic nominee during that same period.

Unions’ declining vote share combined with less dominant Democratic performances with union household voters have made all three Blue Wall states more competitive: after voting reliably Democratic from 1992 to 2012, each narrowly broke for Trump in 2016. Although Biden won all of them back in 2020, he did so by far smaller margins than Obama earned in 2012.

When applying these exit poll results to voter turnout data, we can deduce a rough estimate of how many union household votes Democrats have lost in presidential contests in these three states between 2012 and 2020: 153,064 in Michigan, 77,394 in Pennsylvania, and 152,867 in Wisconsin.

Given these states’ increasingly narrow margins in presidential contests, Democrats’ lost ground with this historically reliable and powerful constituency matters greatly. This was likely a big factor behind Clinton’s struggles in the Midwest in 2016. And, although Biden won all three states in 2020, he only carried union households nationally by 16 points—the second-lowest margin for a Democratic presidential nominee in the past two decades behind Clinton.

Moving forward, Democrats can’t afford to fall much further with these voters. Regaining lost ground, however, could go a long way toward shoring up the party’s standing in their Blue Wall states. There are some recent signs that Democrats are succeeding in their fight to maintain an advantage with union households. For instance, AP VoteCast data show that Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate Josh Shapiro carried these voters by a whopping 22 points en route to a dominant statewide win in last year’s midterm election. That same cycle, Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers won these Badger State voters by 17 points after Biden won them by nine.

However, other candidates in these battlegrounds have struggled to fare much better than Biden with union households. In Wisconsin, Senate candidate Mandela Barnes trailed Evers with them by six points, no doubt hampering his ability to win statewide. Meanwhile, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer outran Biden among these voters by only three points, and in Pennsylvania, Senate candidate John Fetterman outpaced the president by just two. Of course, both Whitmer and Fetterman still won their respective elections, but their inability to rebound to levels of support that previous Democratic candidates enjoyed may be a sign that this bloc’s overall rightward shift is sticking in some places.

Biden himself appears to understand the importance of keeping union voters in the fold. He has said he intends to be “the most pro-union president” in U.S. history and kicked off both of his campaigns in front of union crowds. Early in his administration, he fired Trump Department of Labor appointees considered unfriendly to labor and signed executive orders raising the minimum wage to $15 for all federal employees and on all federal contracts. He strongly supported Amazon workers in Alabama who worked to unionize their warehouse. He also pushed for and signed the infrastructure bill, which his administration said would create “good-paying union jobs,” and the Inflation Reduction Act, which included prevailing-wage protections and encouraged energy workers to unionize.

In turn, organized labor has lauded Biden’s first term. The president has already received endorsements from several major labor groups, including the AFL-CIO, AFSCME, and AFT. They also constitute some of the largest donors to the DNC so far in the 2024 election cycle. This makes it clear that much of the top union brass is on board with a second Biden term.

What remains to be seen, however, is whether the rank-and-file follows suit—especially in the Midwest, where union members often still resemble the stereotype of years past: white and working class. In 2020, white, non-college voters constituted a majority of the electorate in Michigan (54 percent), Pennsylvania (53 percent), and Wisconsin (58 percent). While this demographic is still likelier than not to vote Republican, non-college white voters who are unionized were less likely to back Trump in 2020 compared to those who were not. And while these voters are often more culturally moderate or even conservative, many embrace economic populism and highly approve of unions, giving Biden and Democrats an opportunity to make greater inroads.

Polling consistently shows there is fertile ground for Biden to promote a pro-union message heading into 2024. According to Gallup, which has tracked union favorability for decades, Americans’ approval of unions is at a half-century high. A 2023 Pew survey also found that many people see the decline of unions as a bad thing for the country as a whole and for working Americans, specifically. Earlier this year, a major report examining Democrats’ struggles in “factory towns” found that messages affirming the value of unions resonated deeply with voters in these areas, including conservatives.

One Blue Wall state where Democrats are already leaning into this pro-union push is Michigan. The party used its newly minted governing trifecta there to repeal the state’s “right-to-work” law earlier this year, which was enacted a little over a decade ago under a Republican government. However, Democrats have also experienced headaches with an influential labor group in Michigan: the United Auto Workers, which expressed frustration after the Biden administration steered federal funding to non-union EV suppliers (and just today announced a strike at three plants in the Midwest). As a result, they’ve withheld their endorsement of his re-election campaign—and Trump has even tried to capitalize off of this seeming rift by pursuing an endorsement of his own. Election handicappers consider Michigan the least competitive of the three Blue Wall states heading into 2024, but if Biden’s troubles with the UAW persist, it could signal deeper problems with union voters in the state.

Democrats also likely have some work to do to repair their relationship with union-household presidential voters is Pennsylvania. Exit polls indicate that the party’s standing among these voters here is in worse shape than in Michigan and Wisconsin. Biden lost them to Trump in the Keystone State by two points, and while the exits didn’t ask about union affiliation in 2016, Clinton’s loss here—driven by steep drop-off from Obama in white, working-class parts of the state—indicates she likely fared even worse than Biden.1

Though their share of the electorate has steadily declined in recent years, union households still represent a crucial piece of the Democratic coalition in the Blue Wall states, and a sweep of those states will almost certainly guarantee Biden a second term. Improving margins among this voting bloc may prove to be a vital part of the party’s path to victory. Biden obviously knows this. The question is now whether he and other Democratic candidates can message their accomplishments effectively enough to secure solid margins with these voters. Their success or failure in doing so could make the difference in a close race.

The AP VoteCast survey shows that Biden actually won these voters in 2020, but only by about five points—and again by a smaller margin than in the rest of the Blue Wall.