Tuned-Out Voters are the Most Negative on the Economy

The people who pay the least amount of attention to politics—yet still vote—hold the gloomiest views about the state of the economy and inflation.

There’s been a lot of talk recently in media and policy circles about the issue of “economic vibes” versus “economic reality” as expressed by government and private sector statistics. Or in plain language, “Why do so many Americans have negative views of the economy despite many positive overall economic indicators?”

Several recent analyses provide descriptive evidence that the U.S. is a real outlier in terms of public opinion corresponding to hard economic indicators. The best example of this is an interesting piece by the Financial Times’s data guy, John Burn-Murdoch, that shows the discrepancy between consumer confidence and actual economic indicators across several developed countries. His conclusion:

Relative to the eve of the pandemic, US consumers now appear gloomier than the French, the Germans and even the British. The Europeans all feel about as confident as one might expect based on how their economies are performing. Disproportionate doom seems to be a new American affliction.

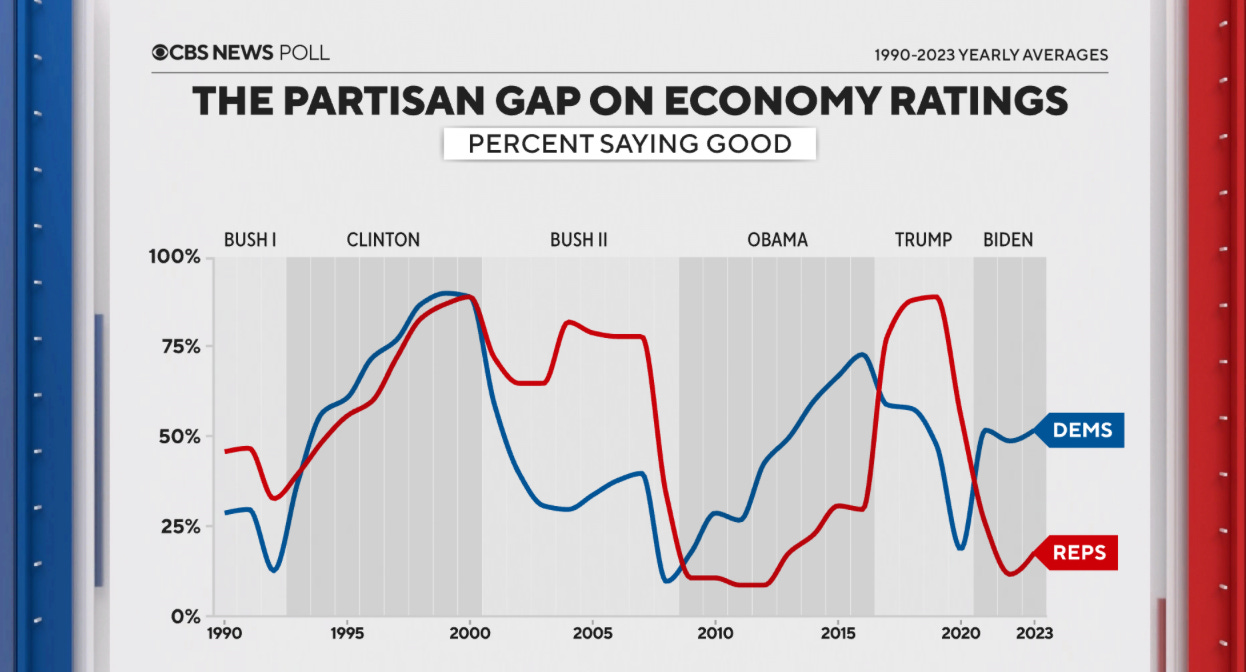

Separate from consumer confidence data, it’s well established in other public opinion research that partisan interpretations of the economy have been growing over the past two decades—i.e., party supporters of the sitting president rate the economy and the president’s handling of it more favorably than do members of the opposite party, regardless of actual economic performance. Supporters of both parties exhibit this behavior with Republicans generally showing wider swings in attitudes depending on who’s in power. Here is a good illustration of this trend over time from CBS News polling:

Adding to the descriptive mix, but not resolving this debate, recent TLP/YouGov national polling offers some interesting data worth considering.

It turns out the voters who pay the least amount of attention to politics are the most negative in their overall evaluations of the economy and in terms of their own personal financial situations.

Who are these voters?

Around 16 percent of registered voters overall say they follow what’s going on in government and public affairs “only now and then” (11 percent) or “hardly at all” (5 percent).

The least tuned-in Americans are still voters, however. Eighty percent of the least engaged group (those who follow government and public affairs hardly at all) said they voted in the 2020 election, and 74 percent of this group say they definitely will vote, or probably will vote in the 2024 election, with 14 percent unsure.

In terms of party support, the least tuned-in group reported voting for Biden over Trump by an 8-point margin in 2020.

Ahead of 2024, the least tuned-in group is evenly split between the two likely nominees: 34 percent say they will support Biden and 34 percent will support Trump, while 18 percent are undecided and 11 percent wouldn’t vote.

The least tuned-in group is also by far the most moderate of any other political interest group: 61 percent of those who pay attention to government hardly at all say they are moderate compared to less than half of those across all other political interest categories.

Similarly, nearly 6 in 10 of the least tuned-in group are unsure of whether they are politically on “the left” or on “the right”.

Not surprisingly, the least tuned-in also report the highest levels of distrust of the news across political interest groups—nearly two-thirds of these voters say they trust the news they see just a little or not at all, compared to less than half of those who follow politics most or some of the time.

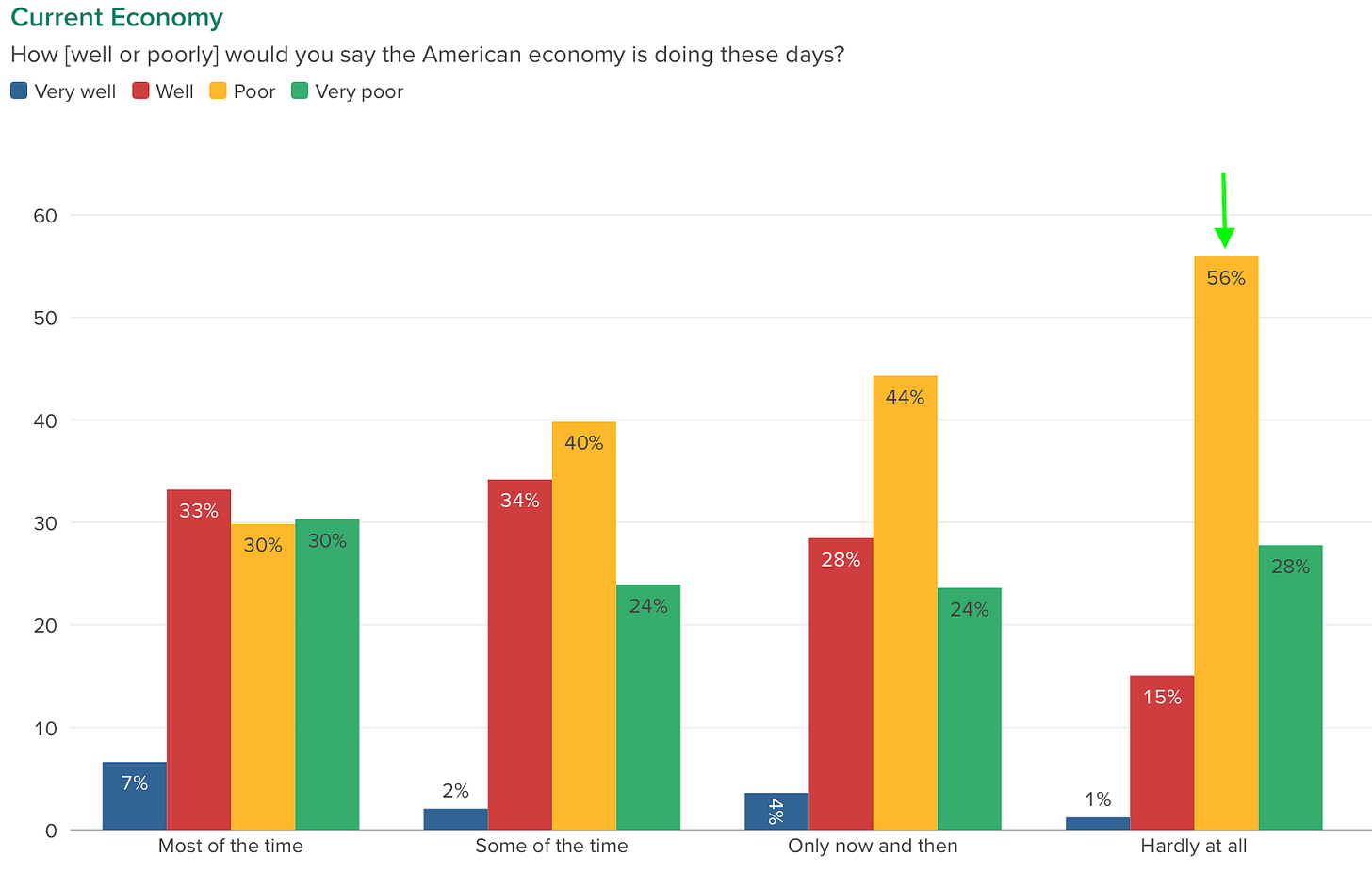

Notably, the least tuned-in to politics voters report the most pessimistic views of the economy. As seen below, 56 percent of those who follow politics hardly at all say that the American economy is poor these days with another 28 percent saying it is very poor. In comparison, around 3 in 10 voters who follow public affairs most of the time rate the economy as poor or very poor, respectively, with more than twice the number saying the economy is doing well or very well.

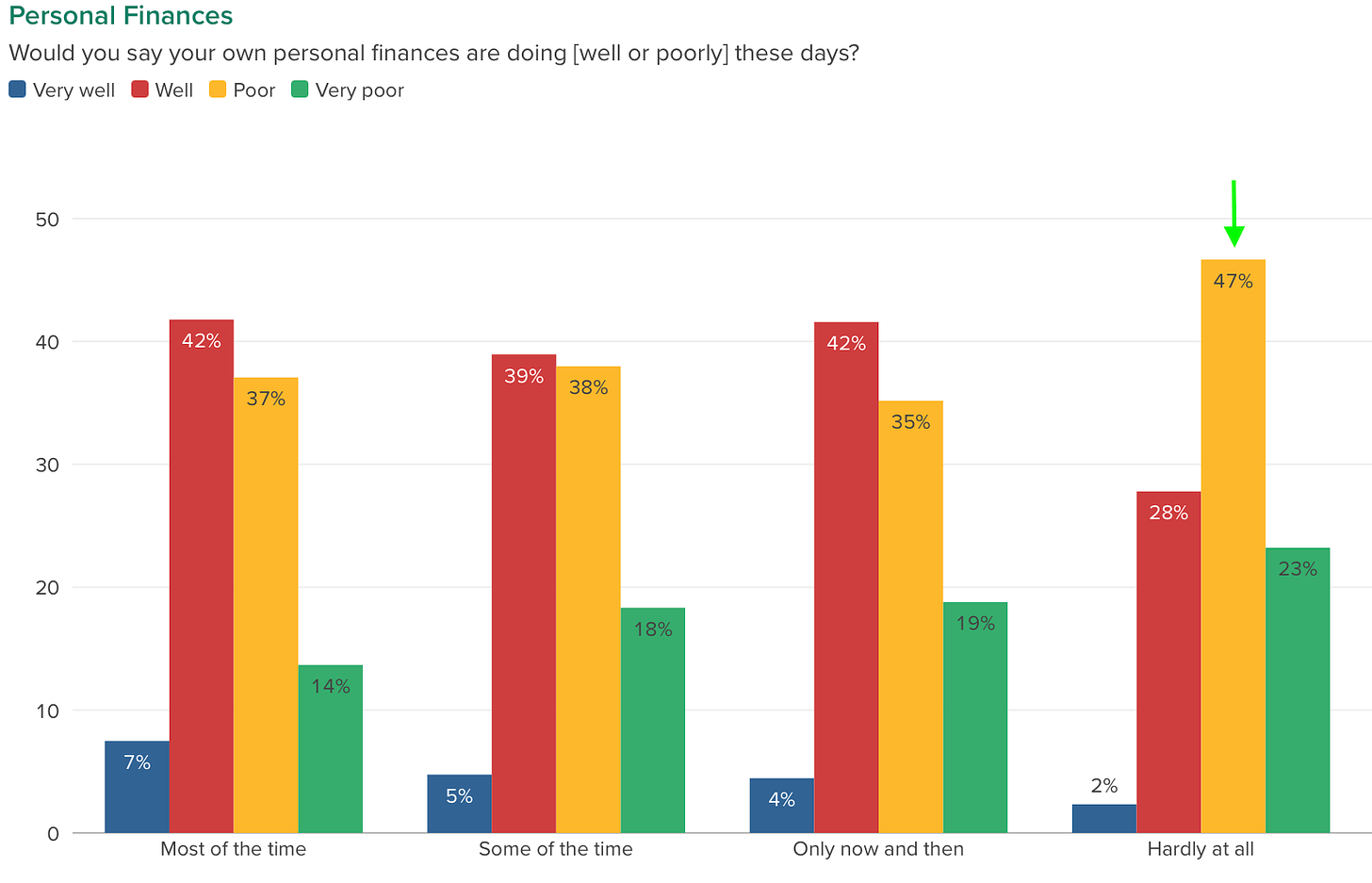

Evaluations are equally grim on the personal side. As seen below, 70 percent of those who follow politics hardly at all say their own personal finances are doing poorly or very poorly these days—19 points higher than those who pay attention to politics most of the time.

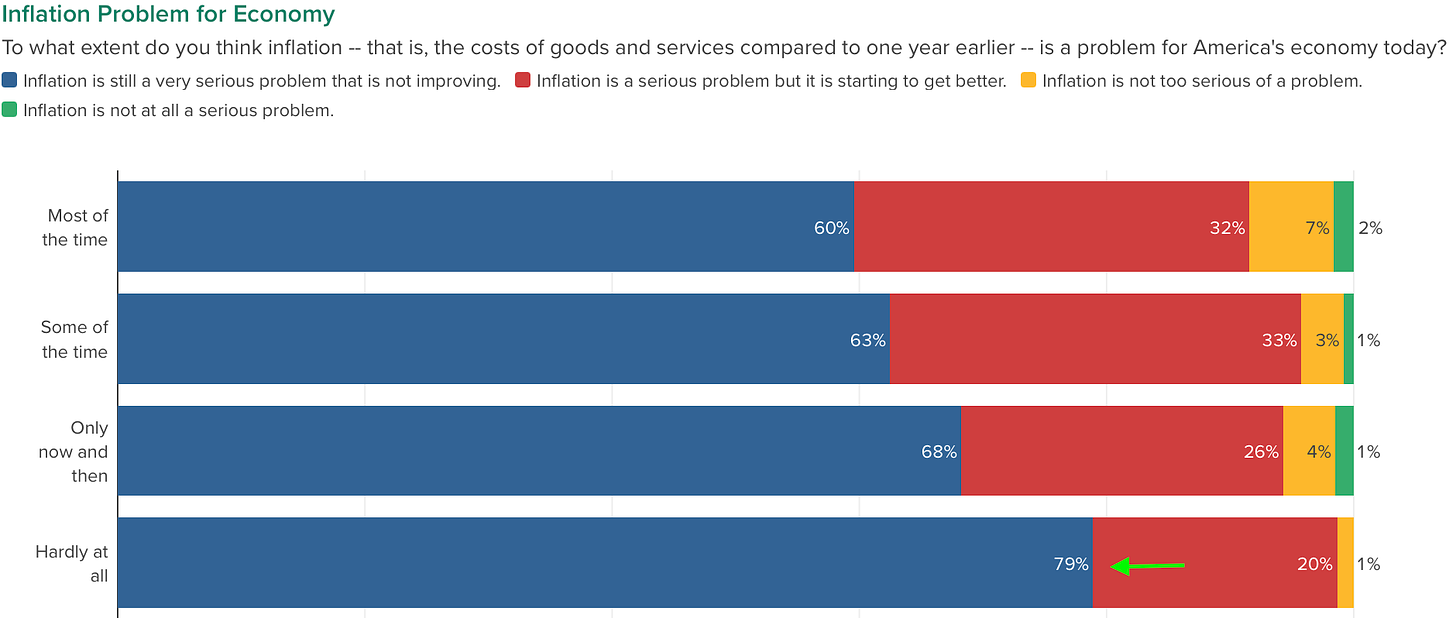

Likewise, the least tuned-in voters also report the most negative views about the direction of U.S. inflation—nearly 80 percent say that inflation is still a very serious problem that is not improving compared to 60 percent of those who pay attention to politics most of the time.

Unfortunately, it is basically impossible for these or any other findings to empirically confirm or reject the “vibes” theory of the economy since there’s no way to clearly measure what exactly is having an impact on whom and for what reason.

Are the least tuned-in voters the most negative on the economy because they absorb all the bad vibes and relentless media negativity in the ether without getting any contravening facts or information? Or do they feel this way independent of the larger economic narrative they may or may not be absorbing?

The vibes theory makes some intuitive sense, of course—contemporary media coverage, social media discourse, and America’s crazy partisan politics probably have some impact on voters’ views in ways that aren’t entirely grounded in facts or reality.

Yet, barring some clearer definition of what “vibes” actually are and how they affect voters, it’s a bit of a circular stab in the dark that seems hard to prove or disprove: "People say the economy is bad because people say the economy is bad.”

Some supporters of Biden say the economic vibes are off and that media or partisan negativity is causing the problems with his ratings despite job numbers being good and inflation coming down from recent highs. Other Biden backers say the vibes are off because things really aren’t that good, and many Americans are still facing hard times over inflation and other cost of living issues. Meanwhile, Republican opponents of Biden say both the vibes and economic reality are bad because Biden is doing a poor job as president, and his policies are making it worse. And economic data analysts, like the FT’s Burn-Murdoch, say that actual consumer spending is a better measure of what people really think about the economy than vibes-influenced surveys.

The head spins.

Ultimately, in political terms, the vibes debate doesn’t need resolution.

Regardless of the cause of these attitudes, the fact remains that the voters most chapped about the economy are also the ones least likely to pay attention to any news reports (which they mostly don’t trust) or campaign messaging and outreach (which they have little interest in).

Despite constituting a relatively small proportion of the overall electorate, the decisions of these “least tuned-in but most disgruntled” voters will likely play an outsized role in determining what is sure to be a close election in a handful of states. These moderate Americans may be tuned-out from the media and traditional politics but most of them will still vote in 2024. And these voters are currently split on whether to back Biden or Trump—or vote for a third party or just stay home.

The problem for both Democrats and Republicans is how to talk with economically disgruntled voters who don’t want hear their pitches and won’t believe them anyway.

Fixing the vibes, or trying to cash in on them, is a futile endeavor when the primary challenge for Biden and Trump is that a key segment of Americans—who haven’t fully made up their mind yet—don’t trust either one of them to address the problems they see in their own lives and in the national economy.

Bad vibes exist all around—on the economy, on the candidates, and on the political parties and institutions overall.