"To avoid the worst impacts of climate change, scientists say…"

One of the most oft-repeated phrases in the climate discussion is also one of the most vacuous.

We heard a very familiar framing of the climate change problem coming out of the 28th annual United Nations (UN) climate negotiations in Dubai last month. Journalists covering this event leaned on the crutch of using some form of this phrase: “In order to avoid the worst impacts of climate change, scientists say CO2 emissions must be reduced fast enough so that global warming does not exceed 1.5°C above preindustrial levels”.

Here is how The New York Times put it:

World leaders on Friday, in opening speeches at the United Nations climate summit in Dubai, called for action to keep global warming at no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, a target set when the Paris Agreement was adopted in 2015. That’s the threshold beyond which, scientists say, humans will have trouble adapting to intensifying wildfires, heat waves, drought and storms. [Emphasis added]

And Reuters:

That would be the first time in history that a U.N. climate summit has mentioned reducing use of all fossil fuels. But it would fall short of the ‘phase-out’ of coal, oil and natural gas scientists say must happen soon to avoid climate change escalating. [Emphasis added]

The Wall Street Journal covered it in a similar way:

An agreement targeting fossil fuels would send a broad signal to the global economy that governments are intent on sharply cutting fossil-fuel consumption…such a deal would represent an unprecedented acknowledgment…of what scientists say is needed to prevent the more destructive effects of climate change. [Emphasis added]

This framing is hardly new—it has been nearly ubiquitous in climate coverage over the past five years. Here is just one more example from CNN:

To avoid the worst consequences of climate change—worsening extreme weather, irreversible ecosystem shifts, loss of life and economic hardship—scientists say the world must limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.” [Emphasis added]

Since global temperatures rise in step with total cumulative CO2 emissions, setting a global warming limit at 1.5°C entails that there is a definitive global carbon budget or a certain amount of “allowable CO2 emissions” that humanity will exhaust in a matter of years. Under this framing, a deadline is quickly approaching, and the remaining “carbon budget” should not be exceeded but instead can be distributed or allocated to countries based, perhaps, on the judgments of scholars.

But this framing misleads for at least three reasons.

The first is that the phrase “scientists say” implies that there is a scientific consensus on the need to limit global warming to some particular level and therefore a scientific consensus on the size of our supposed carbon budget. That is not the case.

The second reason is that tying the phrase “in order to avoid the worst impacts of climate change” to the particular 1.5°C level of warming implies that there is something special about that threshold. But that’s not the case either.

Finally, focusing only on “scientists” and “the worst impacts of climate change” takes an issue that should be looked at through a society-wide cost-benefit lens and puts the focus exclusively on the benefits of avoided warming—ignoring the costs involved in avoiding that warming.

What do “scientists say” about climate change?

A phrase as all-encompassing and general as “scientists say” should be reserved for claims with a very robust scientific consensus.

That does indeed apply to the claims that the planet is warming and that human activities are the primary driver of that warming. You will often hear that there is a “97 percent scientific consensus on climate change,” and that again refers to various surveys of the scientific literature that tend to consistently find something like 97 percent of climate scientists and relevant climate science papers support the conclusion that humans are causing most (typically all) of contemporary global warming.

But there is much less of a consensus on the impacts of that warming, particularly the relative magnitude of those impacts on human society in the context of all other dynamic, rapidly evolving changes in technology, infrastructure, and societal organization.

The so-called “Working Group 2” of the IPCC covers the impacts of climate change. In my view, Working Group 2 tends to bend over backward to portray climate change impacts as negatively as possible. Furthermore, the entire notion of defining the preindustrial climate as some ideal state is dubious. Despite this, even the IPCC Working Group 2 reports do not claim that there is anything particularly special about the 1.5°C level of global warming and its associated global carbon budget. Instead, as shown by some of their figures below, they highlight changes in the climate system and risks of adverse consequences on a continuum of levels of global warming.

[Figure 1 from IPCC Working Group 2 showing three important physical measures of climate change - extreme heat, soil moisture (a measure of drought), and extreme precipitation (associated with flooding) on a continuum of levels of global warming.]

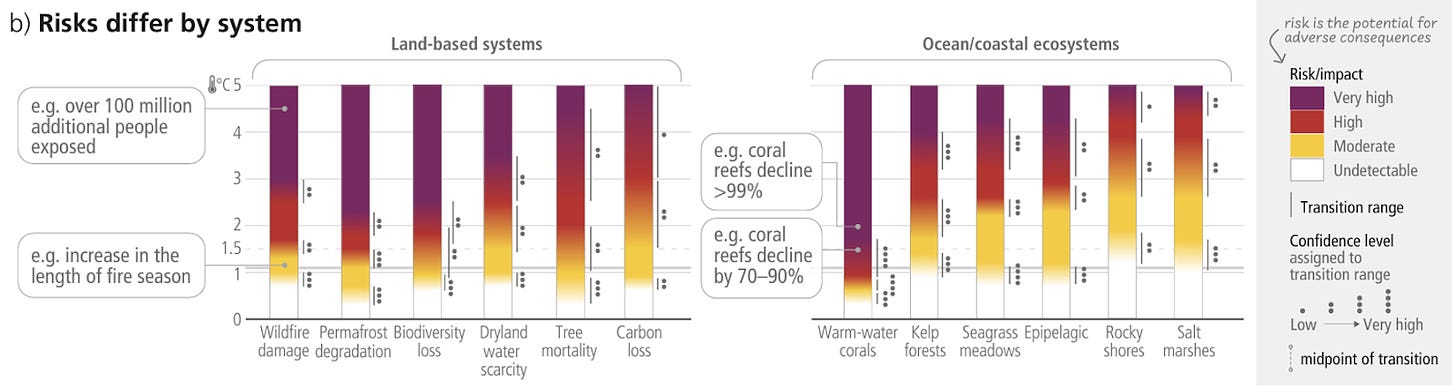

[Figure 2 from IPCC Working Group 2 showing risks to various systems on a continuum of levels of global warming, varying by system.]

The IPCC broadly frames climate impacts as getting incrementally worse with increased global temperature. But what about thresholds or “tipping points?”

There are certainly elements of the global climate system that will exhibit threshold behavior and respond non-linearly to warming. Think the melting of certain ice sheets, the characteristics of tropical ecosystems like rainforests, and the strength of particular ocean circulations, for instance.

Potential tipping points associated with these systems and others are certainly concerning, but they do not justify any particular global temperature limit or definitive carbon budget. This is because the systems that might tip are constrained in spatial extent; they are diverse in terms of how much warming might cause them to tip, and there is substantial uncertainty around how much warming might cause each of them to tip. There is no compelling evidence for a general relation between the overall number of abrupt shifts and the level of global warming. (Also, most of these systems “tip” on timescales of many decades to centuries to even millennia, which are abrupt in geologic terms but slow on human timescales). This all means that more global warming is associated with more risk on a relatively smooth continuum without any justification for a particular global temperature limit.

Furthermore, the research on tipping points seems to be at least partially politically motivated. In 2007, perhaps the most high-profile paper on the topic to that point stated:

Many of the systems we consider do not yet have convincingly established tipping points. Nevertheless, increasing political demand to define and justify binding temperature targets, …makes it timely to review potential tipping elements in the climate system under anthropogenic forcing.” [Emphasis added)

To summarize, there is no justification to tether any particular amount of warming like 1.5°C to the phrase “in order to avoid the worst impacts of climate change,” and in fact, it could be attached to any amount of warming.

So if there’s nothing special about the 1.5°C level of global warming from a climate impacts perspective, where did it come from?

A 2°C global warming limit was first proposed in the late 1970s, long before sophisticated studies of climate impacts had emerged, essentially because it was a round number and thought to represent the warmest the earth had been in 100,000 years. By 1992, the 2°C limit had solidified as conventional wisdom for the amount of warming humanity would like to avoid, and this number was officially codified as “dangerous interference with the climate system” by the UN in the 2009 Copenhagen Accord. Six years later, the UN Paris Agreement affirmed the 2°C goal but, under pressure from environmentalists and certain diplomats, also articulated aspirations for limiting global warming to only 1.5°C.

Only after promulgating this 1.5°C limit did the UN solicit a report from the IPCC to support it. Coverage of this 2018 report widely spread the false claim that the IPCC had concluded that humanity had until 2030 (or 12 years at the time) to avoid 1.5°C and catastrophic impacts. This idea may have been most famously articulated by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY):

Millennials and Gen Z and all these folks that come after us are looking up, and we're like, 'The world is going to end in 12 years if we don't address climate change, and your biggest issue is how are we gonna pay for it?'

But the actual report made no such claim. The report was tasked with evaluating the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C and comparing them to those associated with 2.0°C, as well as evaluating the changes to global energy systems that would be necessary in order to limit global warming to 1.5°C. It was not tasked with asking what temperature level might be considered to be catastrophic, nor did the word catastrophic itself appear in the report.

Bottom line: the 1.5°C limit and the associated carbon budget emerged from the collective judgment of elite policy actors, not the consensus of scientists. It should not be construed as some sort of definitive scientific conclusion.

Because of this, when the IPCC turns its attention to evaluating the feasibility of limiting global warming to 1.5°C or 2.0°C by 2100, it takes those limits as starting points and then discusses the transitions in the agricultural and energy systems necessary to adhere to those limits.

[Figure 3 from IPCC Working Group 3 showing three CO2 emissions trajectories associated with different amounts of global warming by 2100.]

But what about the costs of limiting warming?

Something striking about the figure above is the vast gap between the CO2 emissions pathway associated with already “Implemented policies” and the pathway that would be required to “Limit warming to 1.5°C”. Climate activists tend to view this gap as proof of a broken political system overtaken by plutocrats and fossil fuel interests. However, this explanation is far-fetched given the influence and power of environmentalist organizations and environmental philanthropy, and given that reducing CO2 emissions would be such a strong PR win for so many political leaders and even corporate executives. A much more straightforward explanation is that fossil fuels remain good at providing cost-effective energy, the foundation of modern society, and that the 1.5°C pathway would simply be too costly from the perspective of human well-being.

After all, consider that the black line above illustrates society’s historical increases in CO2 emissions, which have coincided with almost all climate-sensitive aspects of global human society trending in positive directions in recent decades despite the ~1.3°C of warming since the industrial revolution: crop yields and calories available per person have increased, death rates from malnutrition and famines have decreased, the share of the population with access to safe drinking water has gone up, the rates of climate-influenced diseases like malaria and diarrheal disease have gone down, death rates from natural disasters and non-optimal temperatures (hot and cold) have declined, and the fraction of people in extreme poverty has plummeted. These trends have been enabled by fossil-fueled industrialization, which is why fossil fuels are so difficult to quit.

Despite these positive trends globally, tremendous inequality persists today, with 3 billion people still in extreme energy poverty and the observed average mortality from floods, droughts, and storms 15 times higher for low-energy use (and thus low emitting) countries than for high-energy use (and thus high emitting) countries. Even in high-energy-use countries like the US, many families at the lower end of the income distribution are forced to endure harmful indoor temperatures or even sacrifice medicine or food in order to pay for energy costs.

The point is that any policy that restricts energy options by defining strict carbon budgets necessarily eliminates some options and holds the strong potential to harm human resilience to climate as well as human well-being overall. To put more concrete numbers on the 1.5°C emissions pathway, coal power plants would have to be phased out at an average rate of about 240 plants a year, every year between now and 2030, to be on pace for the target. Overall, it is a rate of greenhouse gas emissions reductions that is equivalent to what was experienced due to the COVID lockdowns and associated economic recession (about five percent) but maintained year after year for the next 4-5 decades. The costs, in monetary terms, are calculated to be something close to five to ten percent of global GDP (or $5-10 trillion) annually over the next several decades.

But costs like these are completely ignored in the phrase “in order to avoid the worst effects of climate change, scientists say…” because “effects” only refers to the negative impacts of warming, not the costs of overly restrictive global energy policy involved in allocating a dwindling “carbon budget.”

Ditch the vacuous framing.

In coming years, the carbon budget associated with the 1.5°C limit will be exceeded—and the climate commentariat will be forced to at least consider new ways to frame the discussion. Rather than simply resetting with a new artificial limit and carbon budget (e.g., moving it back to 2.0°C), climate activists should perhaps place the emphasis much more on the near-term technological developments necessary to reduce the green premiums for low emissions technologies like enhanced geothermal, advanced nuclear reactors, and low carbon steel and cement production. The moment these and other green premiums are eliminated is the moment that economic forces align with political goals to facilitate the necessary transitions to a near-zero emissions economy.

It’s also the moment that contrived temperature limits, carbon budgets, and the COP negotiations themselves become unnecessary.

Patrick T. Brown is a Ph.D. climate scientist, co-director of the Climate and Energy Team at The Breakthrough Institute, and adjunct faculty at Johns Hopkins University.

Editor’s note: This is the fifth installment in “The Climate Report” collaborative series from The Liberal Patriot and The Breakthrough Institute looking at the science and reporting behind extreme weather events and other climate related matters.