TLP's 2024 Swing-State Project: Pennsylvania (Part One)

Examining Pennsylvania's political history and geography

No state may lay claim to being a microcosm of America more than Pennsylvania. On either side of the state rests two major population centers: Pittsburgh in the west and Philadelphia in the east, both of which are heavily Democratic, diverse, and growing, especially in their respective suburbs. Though a handful of similar (if smaller) communities exist elsewhere, much of the rest of the state’s population is spread across rural and exurban communities that are typically whiter and more conservative. This includes industrial, working-class areas in the state’s northeast region; mountainous terrain in the middle of the state, part of which is home to a significant Pennsylvania Dutch population; and ancestrally Democratic territory out west, once a bedrock of the U.S. steel industry and a region where Republicans have made substantial gains since the turn of the century.

Pennsylvania’s electoral trends over the past decade have mirrored the nation’s as a whole. Between 2012 and 2020, many of these rural and exurban communities swung heavily to the right, which in 2016 helped Donald Trump become the first Republican presidential candidate since 1988 to win the state. Though Democrats continue to win big in the major metro areas, they have seen a steady erosion of support from nonwhite voters in the more urban parts of cities like Philadelphia. At the same time, voters with a college degree and those in suburban communities moved leftward over the past decade.

All these trends have made Pennsylvania an enduring political battleground, especially in more recent years. Since 2000, 10 of the state’s 26 races for major statewide offices—president, U.S. Senate, governor, and attorney general—have been decided by fewer than five points, including six of the nine contests in the Trump era. Among the most competitive races have been those for the presidency. Outside of Barack Obama’s 10.3-point win in 2008, no presidential candidate to carry the state this century did so by more than six points. In 2016, Trump won it by just 0.7 points (a margin of 44,292 votes), and when Biden flipped it back four years later, he won by 1.2 points (or 81,660 votes).

Even in such competitive terrain, Democrats have found more statewide success than Republicans over the past decade. In fact, outside of then-U.S. Senator Pat Toomey’s narrow re-election in 2016, Republicans have not won a single top-of-the-ticket race in Pennsylvania since Trump was elected. In the 2022 midterms, Democrats won important elections for governor and U.S. Senate and flipped the state House for the first time since 2008, making Pennsylvania one of just two states in the country with a divided legislature (the other being Michigan). Most recently, the party’s state Supreme Court candidate won in 2023, keeping the Court’s partisan lean tilted toward Democrats.

Still, statewide results are often very close, particularly in presidential years, which experience higher turnout. Heading into the 2024 election, Pennsylvania is again expected to be a pivotal state, as it is among the three “Blue Wall” states (along with Michigan and Wisconsin) that President Biden must win to secure a second term.

2024 Senate Race

Pennsylvania will also host a high-profile U.S. Senate contest, which Democrats must win to keep alive any hope of retaining their majority. Incumbent Democrat Bob Casey—a bipartisan dealmaker and friend of organized labor—is seeking a fourth term. Casey has proven to be a formidable politician during his time in elected office. Since his first successful bid for Pennsylvania state auditor in 2000, he has won every general election race in which he has run—and routinely done so by double digits.1

We must note, though, that Casey has also had the good fortune of running for Senate in cycles that were highly favorable for Democrats. His first campaign was in 2006, a blue wave year, helping him oust incumbent Republican Rick Santorum. In his second race in 2012, he shared the ticket with President Obama, who carried Pennsylvania by 5.4 points in his own re-election bid. In 2018, Casey again benefited from running in a Democratic wave year, trouncing his GOP opponent by 13.1 points two years after Trump won the state.

This year could prove to be more difficult for Casey. He is again sharing the ballot with an incumbent Democratic president, but one who is highly unpopular heading into re-election—Biden’s approval rating in Pennsylvania as of January was just 40 percent. The decline of ticket-splitting since 2012 also means that Casey, who remains far more popular than Biden in Pennsylvania, may nonetheless have trouble running very far ahead of him.

In the 2024 general election, Casey is likely to face Republican Dave McCormick, a businessman who lost the 2022 GOP Senate nomination to TV personality Mehmet Oz by just 950 votes. McCormick self-financed his last campaign to the tune of $14.4 million, and he already raised a strong $6.4 million in his first quarter as a candidate this cycle, including $1 million of his own money. However, he is expected to face some of the same issues this year that dogged him last time. In 2022, Trump vocally opposed McCormick, calling him a “liberal Wall Street Republican,” “not MAGA,” and “soft on China.” While working to ingratiate himself to the Trump base this time, McCormick is also taking fire from Democrats, who are working to paint him as a carpetbagger from Connecticut who holds extreme views on abortion.

Pennsylvanians also have a relatively favorable view of Casey. According to a January Quinnipiac poll, he has a strong net approval, with 51 percent of Pennsylvanians approving of his performance against just 31 percent who disapproved. He has also already raised around $18 million, surpassing his 2006 ($17.9 million) and 2012 ($14.2 million) totals and putting him on pace to easily surpass his 2018 total of $21.8 million. Even if McCormick’s personal wealth allows him to outraise Casey, the Democratic senator has proven he can succeed despite having less money: he trailed his GOP challengers in both 2006 and 2012 but won anyway.

As of January, Casey has led McCormick in every head-to-head poll of the cycle, averaging an eight-point advantage. A Casey win would help Democrats shore up their narrow Senate majority, but a loss would almost certainly doom their ability to maintain it. Still, election handicappers seem to think Casey is favored, at least initially, to secure re-election.

Pennsylvania’s Political Geography

Unlike in some other swing states, winning in Pennsylvania requires Democrats to do more than simply turn out their base. They must also win—or at least hit their vote goals in—more moderate suburban communities and working-class areas that have historically supported their candidates. In Philadelphia, the largest and most Democratic-leaning county, Biden actually lost ground relative to 2016.2 However, he flipped the state because he outperformed Hillary Clinton almost everywhere else, with his largest gains coming in the city’s collar counties as well as the ancestrally Democratic northeast. Given his narrow vote margin the first time around, it’s vital that he maintains or builds on his 2020 performance this year.

Philadelphia

To be sure, running up the score in Philadelphia remains a key part of any Democratic path to victory. It is the largest city and county in the state, constituting 10.7 percent of the vote share, and also the most diverse: a plurality (40.6 percent) of its citizen voting-age population (or CVAP) is black. In 2020, Biden captured a whopping 81.4 percent of the vote here. However, Philly’s support for Democratic presidential candidates decreased slightly over each of the past two presidential elections. After Obama won there by 71.3 points in 2012, Clinton carried it by 67.1 in 2016, and Biden won it by 63.5. Meanwhile, the city has experienced the lowest turnout in the state over the past decade—an average of just 58.2 percent of registered voters cast a ballot in top-of-the-ticket elections—and tied for the second-lowest turnout across the last three presidential cycles. Still, given its strong Democratic lean, Biden and Casey must work to boost turnout here and stop the party’s decade-long slide.

Pittsburgh

Across the state is Allegheny County, home to Pittsburgh. Though not nearly as blue as Philadelphia, it is still deeply Democratic territory, with 59.6 percent of voters here backing Biden, and it makes up only a slightly smaller vote share (10.4 percent) than Philly. Biden actually gained ground on Clinton in Allegheny in 2020—as she had done in 2016 over Obama—outperforming her by 5.8 points. Part of the reason for this may be that a full 40.9 percent of Allegheny residents have a college degree, the third-most of any Pennsylvania county. Average presidential turnout here has mirrored the state as a whole, with 71.3 percent and 71.2 percent of registered voters, respectively, casting a ballot across the last three elections. This means Democrats may have a chance to extract more votes from Allegheny going forward, which could help offset any losses in less friendly territory.

Philly Suburbs

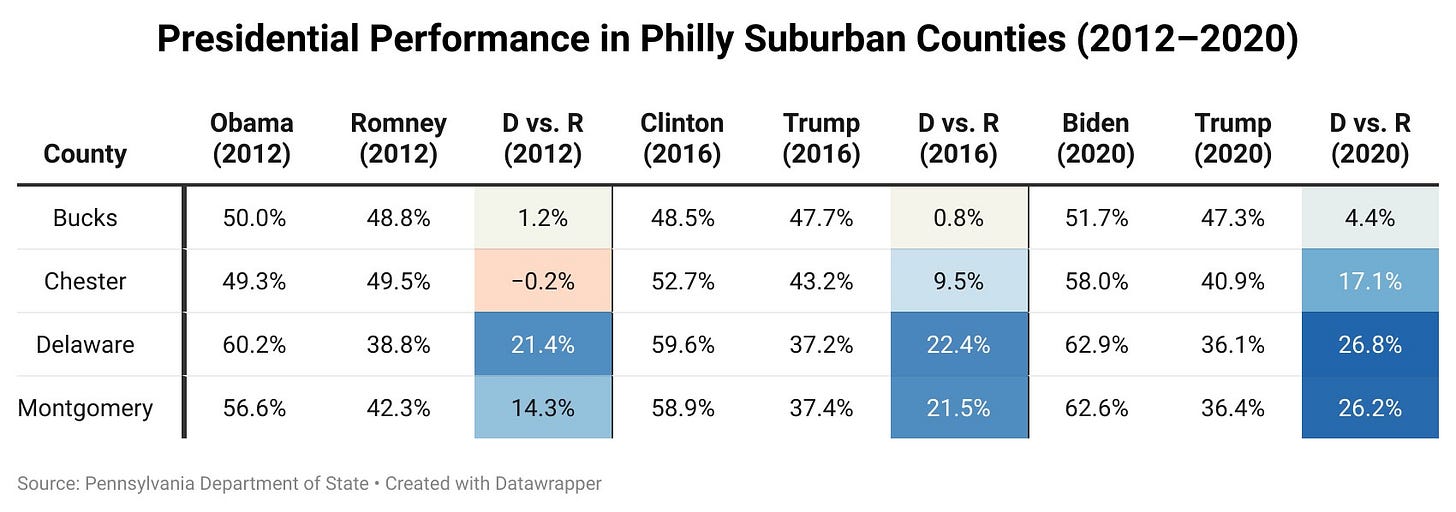

Perhaps the biggest reason for Biden’s success in 2020 was the significant leftward swing of the Philadelphia suburbs, which comprise four counties: Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery. All of them have trended toward Democrats to various degrees over the past decade, and they constituted four of the seven Pennsylvania counties that shifted left by the most between 2012 and 2020. The top two, Chester and Montgomery, embody the type of counties in which Democrats have made gains during the Trump era. Their respective populations grew more than any other county in the state from 2010 to 2020, and they are home to the highest shares of college degree-holders and highest median household income. They also averaged the highest turnout in the last three presidential elections, and in 2020, they were two of the highest-performing Pennsylvania counties for Biden, as he won Chester by 17.1 and Montgomery by 26.2. The leftward swing of Chester is especially impressive, as it narrowly broke for Romney just eight years prior.

The other collar counties—Bucks and Delaware—differ demographically from Chester and Montgomery. Bucks is the oldest and whitest of the four, which may in part explain why it is also the least Democratic-leaning. In the past three presidential elections, Democrats have won the county each time, but they did so by no more than 4.4 points (Biden’s margin). In a reflection of its stable voting patterns, it is also the only Philly collar county where the shares of voter registrations for both parties have remained relatively unchanged over the past decade. Bucks has generally been a good bellwether for statewide performance: only once in the last decade has the county broke differently than the state in a top-of-the-ticket race. This occurred in 2016, when it narrowly backed Clinton by 0.8 points while Trump won Pennsylvania’s electoral votes. When Democratic candidates have carried the county by at least one point, they have won statewide.

Meanwhile, Delaware County (or Delco) is the most racially diverse of the four counties: its white CVAP is under 80 percent (in contrast to the other three), and 19.7 percent of its CVAP is black. Though Delco’s leftward swing from 2012 to 2020 was not nearly as great as Chester’s or Montgomery’s, it gave Biden his second-highest level of support behind only Philly. Turnout here has been the lowest of the collar counties, however, making this another area where Democrats might be able to make further inroads in 2024.

NEPA

Whereas the Philly suburbs represent the type of communities moving toward Democrats, Northeast Pennsylvania (or NEPA) offers the opposite. The region, home to 11 counties, encompasses older, industrial towns in the Lehigh Valley and communities further north like Scranton and Wilkes-Barre. NEPA residents have long voted Democratic, and many voters even still identify as Democrats: the party has a voter-registration advantage in roughly half (five) of the counties here. But this belies recent electoral trends showing that Republicans have gained significant ground in NEPA over the past decade. This movement predominantly occurred between 2012 and 2016, when all 11 counties swung more Republican, including seven by double digits. Though Biden regained ground in 10 of them, he only rebounded to Obama’s margins in one (Lehigh).

The region’s counties share many similar traits: they are mostly older and working-class and have lower levels of college education relative to the statewide average. But there are also important differences that inform the politics of the region, which become more apparent when dividing it into two sets of counties:

The first set of counties includes the four that voted for Biden in 2020: Lackawanna (Scranton), Lehigh (Allentown), Monroe (Stroudsburg), and Northampton (Bethlehem). In general, the median household income here is slightly higher, and residents are better educated. They were likelier than other counties to see greater population growth over the past decade. Lehigh and Monroe are also racially diverse—they have a Hispanic CVAP of 20 percent and 14.3 percent, respectively, and Monroe has a black CVAP of 12.6 percent.

Comparatively, the seven counties that backed Trump are much whiter and poorer and have lower levels of education. They were also likelier to see population loss between 2010 and 2020.

Heading into 2024, Biden must hold the line in this region. Any further erosion here could jeopardize his re-election chances.

Central PA

Central Pennsylvania is the most conservative of the three regions. In 2020, Trump trounced Biden here by 40.2 points, representing a 13.4-point swing from 2012—the greatest rightward shift of any region. Central PA is heavily working-class: no county in the region has a median household income above the statewide level. The most Democratic county in the region is Centre, home to Penn State University. It was the only county here to back Biden and the only one that voted more Democratic between 2012 and 2020. Given the university’s presence here, it is also the best-educated and youngest county in the region. Biden can’t expect to win Central PA in 2024, but stopping the bleeding may be a key part of any path to victory.

Dutch Country

Nine counties in south-central Pennsylvania comprise Dutch Country. This region is the ancestral home of Pennsylvania Dutch inhabitants, many of whom were Amish, Mennonite, and other denominations. Dutch Country’s politics have remained relatively stable over the past decade. Though it has a fairly strong Republican lean—Biden won just 40.8 percent of the vote here—it also only moved rightward from 2012 by 1.3 points. The most Democratic county in the region is Dauphin, home to the state capital of Harrisburg. Dauphin is both the youngest and most diverse county in the region, with a CVAP that is 16.3 percent black and 6.9 percent Hispanic. Dauphin and two other counties—Cumberland (a fast-growing area just across the Susquehanna River from Harrisburg) and Lancaster (home to the eponymous city)—trended more Democratic from 2012 to 2020, offering Democrats a possible avenue for future inroads.

Western PA

Finally, Western Pennsylvania, which covers 12 counties, is the whitest and oldest region in the state. Twenty years ago, Democrats dominated here, especially in the southwest corner, where Al Gore swept every county. Since then, though, the region’s 12 counties have moved rightward. Ten of them voted more Republican in 2020 than in 2000 by double-digit margins, and just one is even remotely in play for Democrats: Erie, an Obama-Trump-Biden county. Trump carried the other 11 by double digits in 2020. Biden would do well to simply minimize his losses here in 2024.

Voter Registration Picture

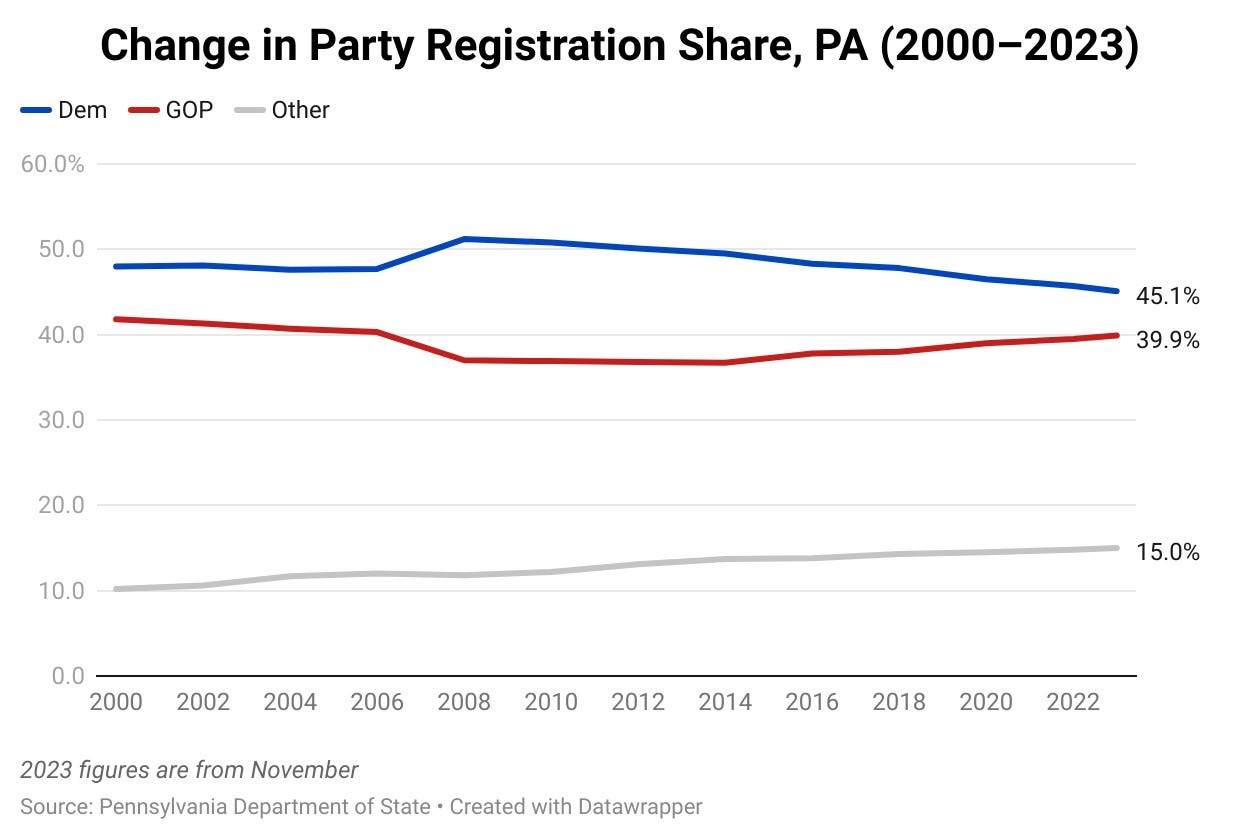

Unlike in many other swing states that track party registration, voters in Pennsylvania are highly likely to affiliate with one of the two major parties. Though the share of voters registering with third parties has steadily grown since the turn of the century, it still only sat at 15 percent as of late 2023, while fully 85 percent remained registered as either Democrats or Republicans.

Overall, registered Democrats have held an advantage over registered Republicans going back to at least 1998. That gap grew substantially between 2006 and 2008, thanks to a concerted effort by then-candidate Barack Obama’s campaign to register new voters and flip independents and Republicans to support him in the state’s presidential primary. The Democrats added 578,828 new voters to their ranks in those two years, more than doubling their advantage over Republicans from just 599,791 voters to 1,236,467. However, since then, that advantage has been steadily fading. As recently as November 2016, registered Democrats still outnumbered registered Republicans by a margin of 916,274. But as of November 2023, that gap had narrowed by more than half to just 446,566.

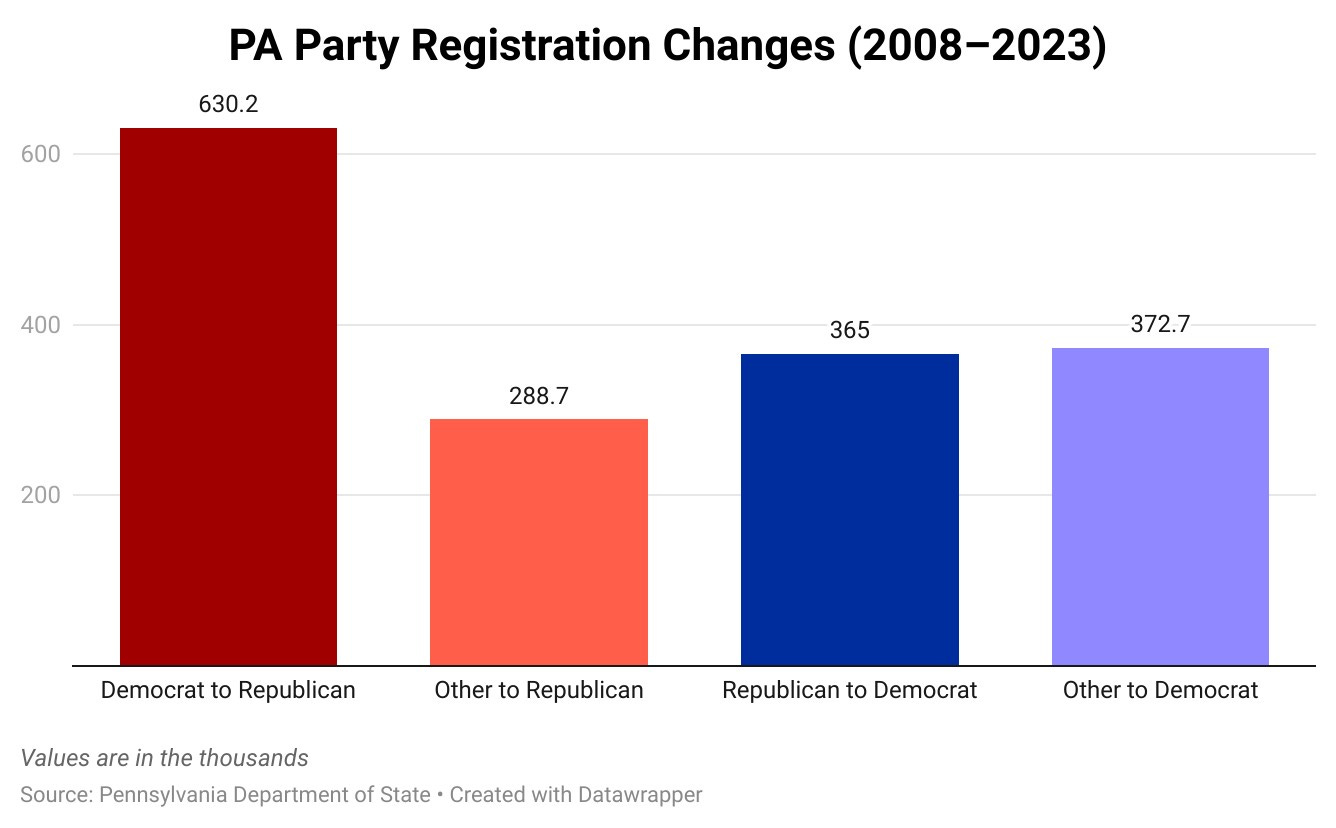

A major reason for Democrats’ fading advantage is likely that many ancestral Democratic voters who had been supporting Republican candidates for some time simply been made their party switch official. In 2016, for instance, 14 of the 23 counties in which Democrats had a registration advantage over Republicans backed Trump, including the state’s three Obama-Trump counties plus several in southwestern Pennsylvania. Four years later, Democrats’ advantage had fallen from 23 to 17 counties, though only four backed Trump—a sign that registration trends had begun catching up to voting behaviors during Trump’s presidency.

Indeed, Trump appeared to be a major catalyst for this change. Ahead of both the 2016 and 2020 elections, erstwhile Democratic voters switched their affiliation to Republican in droves (113,870 and 81,809, respectively). And unfortunately for Democrats, they did not make up nearly as much ground among former Republicans who changed their affiliation to Democratic ahead of those two elections: they picked up just 47,585 (2016) and 49,154 (2020) Republican defectors. One silver lining for Democrats, though, is their slight edge among voters who were previously registered as third-party and re-registered with one of the two major parties. Their largest gains among these voters also came in the two most recent presidential cycles.

One development to keep an eye on in the near term is the implementation of a new automatic voter-registration law in the state. Although some believe this reform will come to benefit Democrats, as it did in places like Oregon, it remains far from certain this will be the case here. Indeed, as the two major parties’ coalitions shift—and as Democrats pick up more highly educated, affluent voters in high-turnout suburban areas—it may be Republicans who reap the rewards of this change, as their base increasingly includes more working-class and rural Pennsylvanians who are less likely to be regular voters. An early 2020 Knight Foundation study found that in Pennsylvania, non-voters preferred Trump over Biden by a margin of 36 to 28 percent. As presidential elections in the state are increasingly decided by narrow margins, this reform could have a profound impact on electoral outcomes in the years ahead.

Historical Turnout Trends

Since the turn of the century, voter turnout in Pennsylvania has been right in the middle of the pack, even despite regularly hosting competitive elections. Turnout in presidential cycles among the state’s voting eligible population (or VEP) averaged 62.4 percent, placing it 24th among all 50 states. In midterm cycles, the state’s average VEP turnout was 44.5 percent, placing it 23rd. Still, Pennsylvania’s turnout has run ahead of the national rate in every election since 2004, and it hit its widest margin in the 2022 midterms, when fully 54.4 percent of Pennsylvania voters cast a ballot compared to 46.2 percent of Americans nationally.

Turnout in the state has varied dramatically from county to county. For instance, deeply Democratic Philadelphia has averaged the lowest turnout as a share of registered voters of any Pennsylvania county over the past decade and notably had the lowest turnout in both the 2020 presidential election and 2022 midterms. What’s more: in eight of the 13 counties that backed Biden for president—which collectively made up nearly a quarter of the vote share in 2020—voter turnout trailed the statewide average (66.5 percent).

Meanwhile, among the 39 counties whose average turnout was equal to or higher than the state average between 2012 and 2022, only five backed Biden. Importantly, three of those counties are among the top four in the state for average turnout, and all three are based in the rapidly growing—and increasingly Democratic—Philadelphia suburbs: Montgomery (73.8 percent), Chester (73.4 percent), and Bucks (71.8 percent).3 The robust turnout in these counties—coupled with Democrats’ growing electoral success in them—has been crucial to the party’s statewide competitiveness, especially when considering that across the other 34 counties where average turnout ran ahead of the statewide average, Trump bested Biden by 30.7 points.

[Part two of this report tomorrow will examine Pennsylvania demographic trends and voting patterns.]

Even in the one contest where his margin was in the single digits—U.S. Senate in 2012—it was still a healthy 9.1 points.

The city and county of Philadelphia are coterminous.

The fourth, Juniata, is a deeply conservative county in central Pennsylvania, though it only made up 0.2 percent of the 2020 vote share.