Three Demographic Trends Underlying Our Growing Partisan Polarization

A look at key shifts likely to re-shape American politics in the coming years.

It’s no secret that partisan loyalties and ideological persuasions amount to some of the strongest dividing lines in America today. When President Biden first took office, he enjoyed the widest partisan approval gap of any president in the modern polling era.1 Before him, Trump had the honor of owning that achievement, and before Trump, it was Obama. Such political divides are also evident among politicians themselves: by one measure, the two major parties in Congress are more ideologically divided today than at any time since the Civil War.

Americans who are loyal to one of the two parties are also increasingly likely to find themselves closer to an ideological pole. According to Gallup, the overwhelming majority of Republicans have long described themselves as “conservative.” Meanwhile, the share of Democrats identifying as “liberal” has steadily grown over the past three decades—finally reaching an outright majority during Trump’s presidency and further widening the ideological chasm separating the country’s two partisan camps.

These types of divides are still the clearest way of understanding the nation’s political trends. For instance, as the two parties become more ideologically homogenous and less open to moderates—and as more voters self-sort into states whose governments better reflect their individual politics—we are bound to see fewer true presidential battlegrounds and less ticket-splitting.

But the country’s shifting political alliances and growing polarization haven’t happened in a vacuum—they’ve been driven by the deepening of demographic fault lines in American life. It’s therefore worth understanding these other divisions and the ways they’re likely to impact politics at all levels of government in the years ahead.

The Diploma Divide

Perhaps the most noteworthy shift underlying the country’s politics in recent years has been the divide between college degree-holders and non-degree holders. This change, which is deeply tied to each group’s evolving views on cultural issues, has played out in a couple different ways.

The first is through ideological self-identification. The Pew Research Center has gauged Americans’ political views over time and found that those who hold at least a college degree have grown much more consistently liberal than those who do not.

These shifts have also played out at the ballot box. In 2012, Obama won college-educated voters by a modest 6.2 points. Four years later, that margin had doubled, as Clinton won them by 12.5 points. By 2020, it had grown by an almost similar margin, with Biden winning this group by 18.4 points. Conversely, non-college voters became more Republican during that time. While Obama won them by 3.1 points in 2012, they voted for Trump by 4.1 points in 2020.

Notably, these changes have been heavily influenced by race. Democrats’ gains with college-educated voters were driven almost entirely by white voters.2 This group broke for Romney by 7.5 points in 2012, narrowly backed Clinton by 0.5 points in 2016, and supported Biden by 9.0 points in 2020. Indeed, white college voters swung more Democratic during that eight-year period than any other major demographic group.3

These shifts can be traced back several decades. College-educated white voters have been trending more Democratic with little interruption since the 1970s. And while both parties were competitive with non-college whites through the latter half of the 20th century, this group began to definitively break toward Republicans around 2000:

While the Democrats’ losses among white voters without a college degree are well documented, it’s also worth noting that their slide over the past decade with the non-college demographic disproportionately came from non-white voters. This bloc moved toward Republicans by a whopping 19 points between 2012 and 2020. In other words, Democrats have been losing ground with non-college voters of all races.

It is possible that these trends will work out for Democrats as more Americans graduate college. As things currently stand, however, non-college voters make up a far greater share of the presidential electorate (62 percent) than do college degree-holders (38 percent). Though it’s difficult to know for sure which party will ultimately benefit the most from this widening “diploma divide,” it’s likely to continue molding both our politics and the culture in profound ways in the coming years.

Young Voters’ Lasting Liberalism

Another front on which these cultural shifts occur is age—and this factor has offered a clear advantage to one of the two parties in recent years. To wit: the youth vote remains stubbornly Democratic at the moment. While it has historically been common for people to grow more conservative as they age, this just doesn’t appear to be happening with millennials.

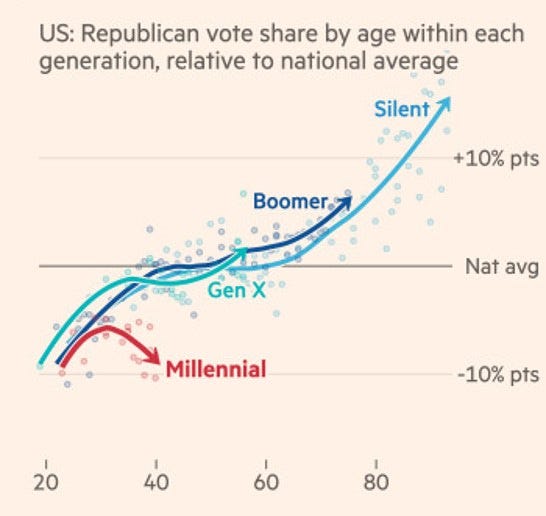

The Financial Times’s John Burn-Murdoch brilliantly documented how compared to the previous three generations—all of whom voted more Republican the further they got into life—millennials have been trending in the opposite direction so far:

This was especially visible in the 2022 midterms, when Gen Z and millennial voters were the lone generation to vote more Democratic in the national U.S. House vote relative to the 2020 election. Moreover, according to the General Social Survey, young people have voted more Democratic in the last four presidential elections—compared to both other age brackets and their own cohort’s past performance—than at any other time in the past half century.

Among the theories for why younger voters are staying liberal into adulthood is that these voters have also adopted other traits that differ from previous generations—traits that have made them more predisposed to voting Democratic. For example, younger Americans are a less religious cohort. Many are getting married later in life and also forgoing having children. Young people are also growing up in a much more tolerant and diverse society than many of their parents did.

Additionally, there is some evidence that the political events that happened during their formative years—the War on Terror, the 2008 financial crisis, the rise of Donald Trump, increased gun violence, climate change—likely left an imprint on them that will not soon be shaken. Political scientists affiliated with the Democratic data firm Catalist have used sophisticated statistical modeling to track differences by age group over time. In a conversation with the Washington Post’s David Byler, they explained:

The events that happen when someone is in or around their teenage years and early 20s has a lifelong impact on their political preferences. For example, I was born in 1982. So when I was in my teens and 20s, Bill Clinton was very popular — followed by George W. Bush being very unpopular. And then a little later than that, Obama wasn’t universally popular — but he was among my [age group]. So, people my age will be, on average, slightly more Democratic.

Byler added:

That’s great news for Democrats. Millennial and Gen Z voters are a growing voting bloc. Some will likely become more conservative with age, but many — like the young Democrats of the Great Depression — may never feel fully comfortable trusting a Republican. And Democrats will benefit from their loyalty.

This phenomenon could obviously change down the road. The issue landscape is never permanent, and while Democrats have benefited in recent cycles from America’s aversion to a Trumpified GOP, team blue has had its own struggles appealing to key voting blocs as well. Moreover, political parties are self-preserving entities, and it’s logical to assume that Republicans will eventually adapt and evolve in response to these trends. They don’t seem to feel the need to do this right now, but a generation of voters that wants nothing to do with them or their policies is a ticking time bomb for the party if it doesn’t figure out how to reach them.

Urban vs. Rural America

A third and final growing fault line is between voters who live in rural and exurban areas and those who live in or near bigger cities. This divide has become more potent as jobs have increasingly moved to large metro areas, attracting highly educated workers who often embrace racial and ethnic diversity and hold more progressive politics. As big cities’ demographics have changed, these areas have also become responsible for a disproportionate share of the nation’s economic output.

Meanwhile, rural communities are reeling: they have experienced “brain drain” and population decline, been hit with worse health outcomes, and seen fewer job opportunities and less economic growth than urban America. Rural areas have also grown more racially diverse at a slower rate than communities near major population hubs. All this and more has engendered greater levels of resentment across geographic lines: people in both urban and rural areas think that those living in other places hold values that are alien from their own.

These cultural and economic changes precipitated monumental shifts in both political attitudes and voting behavior. A recent Bloomberg analysis of voting trends showed that at the turn of the century, metropolitan-area counties voted Democratic about as often as they voted Republican. However, this changed around the time of Barack Obama’s election, when they began voting blue with far more frequency. Conversely, the Republican advantage in rural areas has exploded as the Democratic brand there has become, in the words of former North Dakota Senator Heidi Heitkamp, “toxic.”

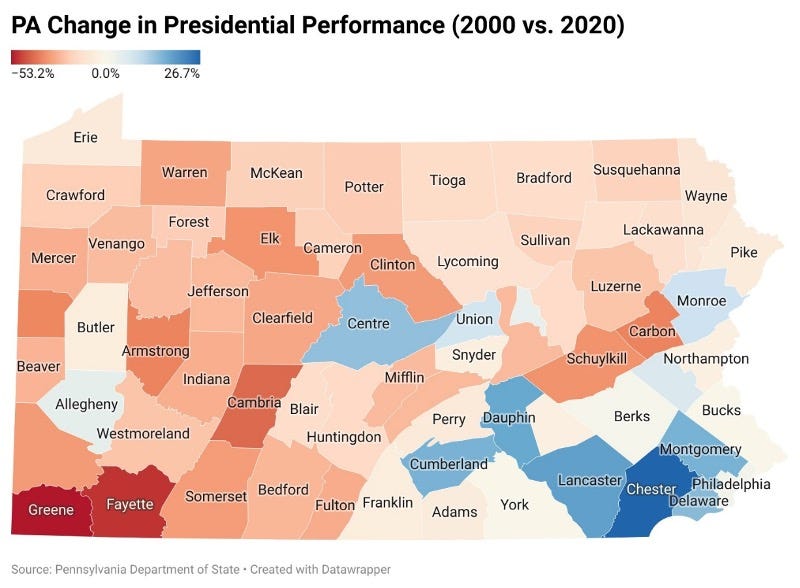

Democrats’ rural erosion is also evident when looking at individual states. Between 2000 and 2020, rural counties across the country (including in pivotal battlegrounds like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin) swung away from Democrats while counties in and around major cities moved toward them.

Unfortunately for Democrats, many of America’s political institutions—including the House, Senate, and Electoral College—have a rural bias, meaning the party’s transition toward a coalition of largely city-dwellers has sometimes carried an electoral penalty. For instance, Democrats lost seats in state legislatures across the country over the past decade because their voters are less efficiently distributed. GOP-controlled legislatures have therefore been able to go through their states’ rural counties to gerrymander themselves into majorities.

Democrats regained some of that ground in recent elections, but rural voters on the whole continue to view the party unfavorably. After they broke Republican by 22.5 points in 2012, rural Americans swung even further rightward in the two subsequent presidential elections, backing Trump by about 33 points. In the 2022 midterms, Democrats fell even further, with rural voters backing GOP House candidates nationally by an astounding 40.1 points.

Of course, Democrats managed to carry the most important battleground states that cycle, but this steady and continued rural erosion has put some erstwhile swing states like Missouri and Ohio out of reach. And if the party keeps falling further, it may jeopardize key swing states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, where 40 percent and 48 percent of 2020 presidential voters, respectively, came from rural communities.

These three trendlines have already had an impact on the nation’s politics. Democratic slippage among non-college voters and in rural areas has led to electoral headaches, as has the GOP’s nagging issues with younger voters. The question over the long term is whether these trends continue or whether either party can break their negative trajectories with key groups. The answer could determine which party gains structural advantages in elections for years to come.

That partisan gap has narrowed somewhat as many self-identified Democrats have cooled on Biden during his first term.

College-educated white Democrats, specifically, have grown more liberal at a faster rate than their non-white and non-college counterparts.

Democrats also gained about 2 points with college-educated Asian Americans during this period. Meanwhile, the party lost ground college-educated black and Hispanic voters.