"This Monster Land"

What John Steinbeck's "Travels with Charley in Search of America" can still tell us about ourselves

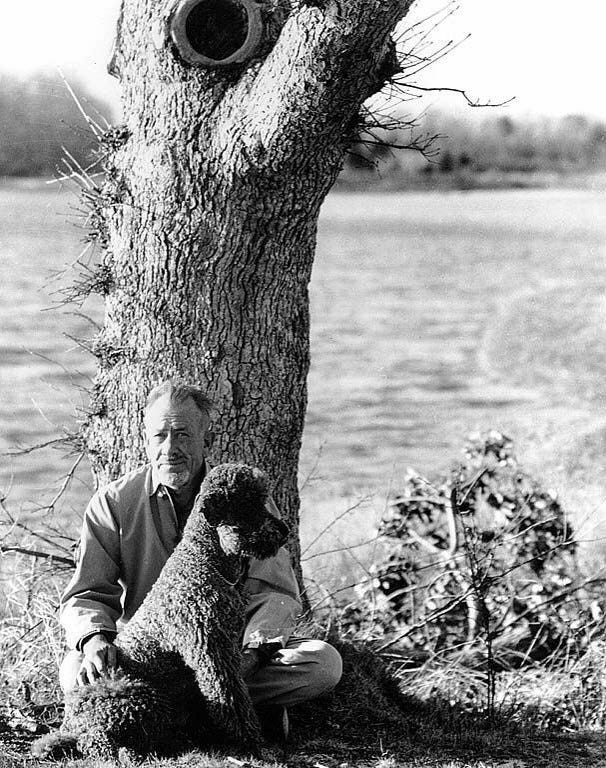

In the fall of 1960, the writer and novelist John Steinbeck set out on a journey across America in a custom-built camper truck with his bleu “old French gentleman poodle” Charley as his only companion. Steinbeck was clear in his own mind about the purpose of his cross-country trip: after spending the better part of twenty-five years outside the United States, he realized “that I did not know my own country.” To remedy this deficiency, Steinbeck set out with Charley to “rediscover this monster land.”

If the exact details and veracity of Steinbeck’s expedition have come under scrutiny in recent years, the enduring lessons his compelling account – aptly titled Travels with Charley in Search of America – still furnishes to readers today remain undiminished. He doesn’t condescend to the people he encounters on the road, even when he clearly finds them wrong-headed or ignorant. Steinbeck presumes a certain level of equality with his fellow citizens, acknowledging that he’s in the same boat as everyone he meets on his journey. He tends to take things and people on their own terms, and as a result Steinbeck’s own judgments come across as fair-minded rather than critical or moralistic.

Steinbeck also portrays America’s natural beauty in vivid terms, all the more so once he passes the Mississippi and reaches the West. The Badlands of North Dakota, for instance, “deserve this name. They are like the work of an evil child. Such a place the Fallen Angels might have built as a spite to Heaven, dry and sharp, desolate and dangerous… A sense comes from it that it does not like or welcome humans.” Likewise, he calls the deserts of the Southwest “a great and mysterious wasteland, a sun-punished place” where in the “waterless air” of night “the stars come down just out of reach of your fingers.”

But he reserves his most evocative descriptions for the redwoods of the Pacific coast:

The redwoods, once seen, leave a mark or create a vision that stays with you always… The feeling they produce is not transferable. From them comes silence and awe. It’s not only their unbelievable stature, nor the color which seems to shift and vary under your eyes, no, they are not like any trees we know, they are ambassadors from another time.

These giants move Steinbeck to reverence, likening the redwood forests to cathedrals where “time and the ordinary divisions of day are changed.”

But Steinbeck’s observations about America itself are equally acute and insightful as those he makes about nature. He expresses a clear unease with the evolution of American society since the end of World War II; “American cities,” he writes early on, “are like badger holes ringed with trash – all of them – surrounded by piles of wrecked and rusting automobiles, and almost smothered with rubbish.” A connoisseur of local dialects and customs – he says he can “remember a time when I could almost pinpoint a man’s place of origin by his speech” – Steinbeck finds the country becoming antiseptic and homogeneous. Radio stations play the same hits whether in Maine or Montana, while roadside restaurants cover everything in clear plastic and provide food that’s “oven-fresh, spotless and tasteless; untouched by human hands.”

Steinbeck has no truck with reactionary nostalgia, however. He sees the clear benefits many of the changes wrought by industrial production and mass communication have had for many Americans: while Steinbeck decries the sterility and uniformity of mass production, he acknowledges that mobile homes, for instance, represent a material step up for many people. “Even while I protest the assembly-line production of our food, our songs, our language, and eventually our souls,” he writes,

I know that it was a rare home that baked good bread in the old days. Mother’s cooking was with rare exceptions poor, that good unpasteurized milk touched only by flies and bits of manure crawled with bacteria, the healthy old-time life was riddled with aches, sudden death from unknown causes, and that sweet local speech I mourn was the child of illiteracy and ignorance. It is the nature of a man as he grows older, a small bridge in time, to protest against change, particularly change for the better. But it is true that we have exchanged corpulence for starvation, and either one will kill us. The lines of change are down. We, or at least I, can have no conception of human life and human thought in a hundred years or fifty years. Perhaps my greatest wisdom is the knowledge that I do not know. The sad ones are those who waste their energy in trying to hold it back, for they can only feel bitterness in loss and no joy in gain.

Steinbeck accordingly stands stupefied by “the great hives of production” on the Great Lakes, cities like Cleveland, Youngstown, and Flint in what would later become the Rust Belt, “the fantastic hugeness and energy of production, a complication that resembles chaos and cannot be.”

Travels with Charley is not an explicitly political book by any means, though politics does intrude on occasion; he travels across the country in an election year, after all, and the Kennedy-backing Steinbeck has it out with his Republican-supporting sisters when he visits them in Monterey. Though he loathes bureaucracy and professes to “admire all nations and hate all governments,” Steinbeck clearly believes in the hardy and rough-hewn liberalism of the New Deal. He greatly admires the Guides to the States published by the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression, for example, proclaiming them “the most comprehensive account of the United States ever got together” and lamenting that they were so “detested by Mr. Roosevelt’s opposition” that some editions only had hundreds of copies made.

Toward the end of his narrative, Steinbeck confesses that he can’t say that he “went out to find the truth about my country and I found it.” That makes the second half of the book’s title, In Search of America, all the more fitting, since Steinbeck’s account is as much about the search itself as anything else. But he nonetheless comes to certain conclusions about this “monster of a land, this mightiest of nations, this spawn of the future” based on his travels with Charley, ones informed by his own sojourns outside the United States – the most elemental being that America does in fact constitute a nation in its own right:

For all of our enormous geographic range, for all of our sectionalism, for all our interwoven breeds drawn from every part of the ethnic world, we are a nation, a new breed. Americans are much more American than they are Northerners, Southerners, or Easterners. And descendants of English, Irish, Italian, Jewish, German, Polish are essentially American. This is not patriotic whoop-de-do; it is carefully observed fact. California Chinese, Boston Irish, Wisconsin German, yes, and Alabama Negroes, have more in common than they have apart… It is a fact that Americans from all sections and of all racial extractions are more alike than the Welsh are like the English, the Lancashireman like the Cockney, or for that matter the Lowland Scot like the Highlander. It is astonishing that this has happened in less than two hundred years and most of it in the last fifty. The American identity is an exact and provable thing.

The fact Steinbeck can’t quite put his finger specifically on that “exact and provable thing” doesn’t make his observation any less true.

There’s a lot more that could be said about Travels with Charley, from Steinbeck’s take on the “state of mind” that is Texas to his use of Charley as a semi-comic foil to his own human conceits – observing Charley, Steinbeck becomes “convinced that basically dogs think humans are nuts.” Nor does he shy away from the darker facets of humanity, as his blood-curdling account of vicious, attention-seeking anti-civil rights protestors in New Orleans makes clear. It takes little imagination to see the parallel between these “crazy actors playing to a crazy audience” and certain contemporary political leaders.

But it’s Steinbeck’s own basic sense of humanity that fills every page of Travels with Charley and makes it worth reading sixty years after its initial publication. It’s a great little volume that manages to embody and transcend its own times, all while teaching lessons about America that endure to this day.