The Two Parties Fail to Understand Place-Based Inequality

New data on the racial/class dimensions of mobility shows the limits of left and right thinking on economic advancement for all Americans.

Democrats and Republicans both have immutable narratives about who is left behind in American life and who deserves the most assistance and political attention. For Democrats, it’s “black and brown people” and for Republicans it’s the “white working class”—a sectarian racial battle tailor-made to produce deep schisms and mutual animosity between Americans.

But according to a massive new study of intergenerational income shifts, led by Harvard economist Raj Chetty and colleagues and researchers at the U.S. Census Bureau, both party narratives fail miserably at representing the reality of economic mobility in America today and both miss the critical importance of communities and place-based approaches to helping lower-income people of all races get ahead in life.

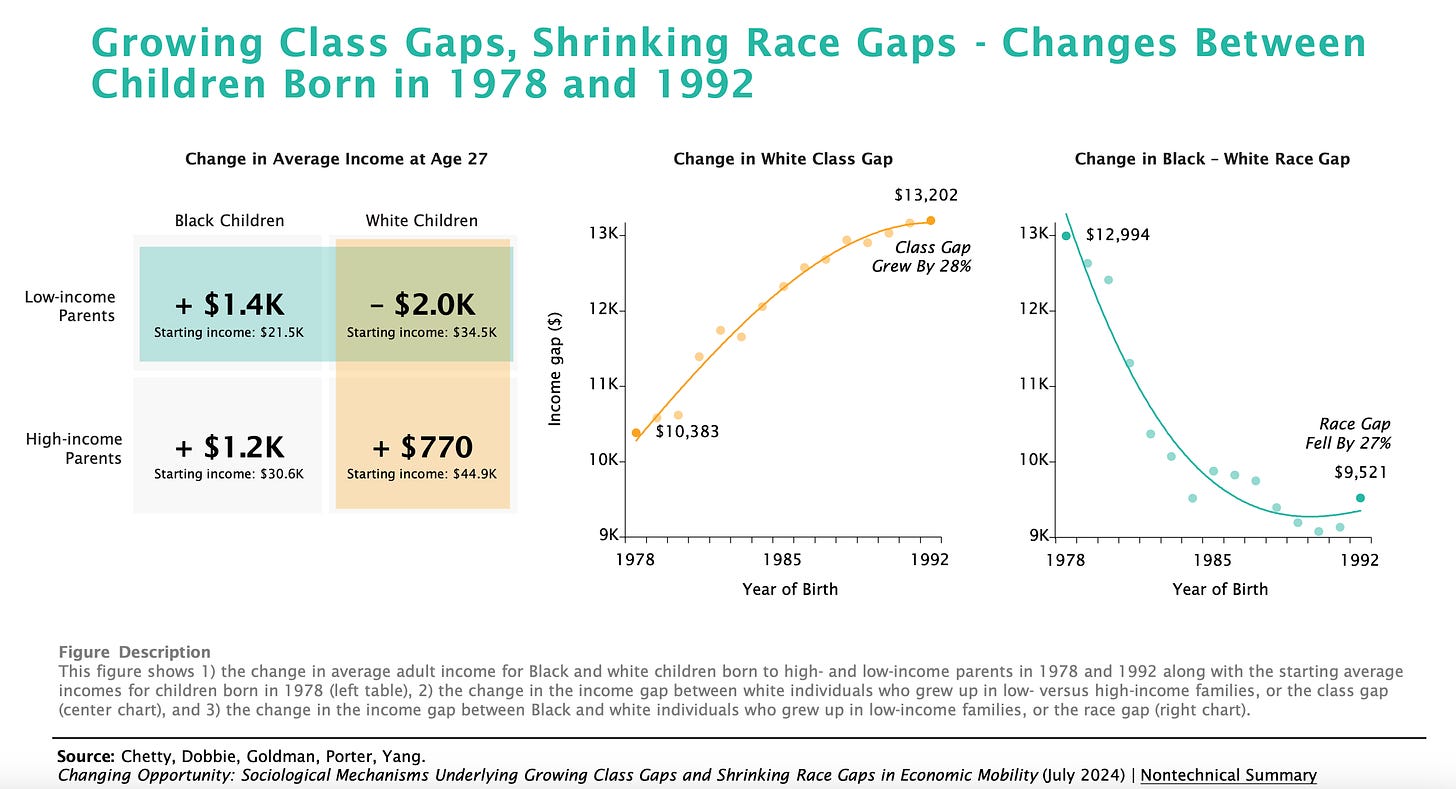

As their charts above highlight, examining anonymous Census and tax data from 57 million children born in between 1978 and 1992, racial income gaps have dropped considerably in recent decades while class gaps among white people have grown substantially:

White children born to low-income (25th percentile) parents in 1992 grew up to earn less on average than white children born to low-income parents in 1978. Over this same period, income increased for white children born to in high-income (75th percentile) families. These divergent trends resulted in growing class gaps among white children. The gap in average household incomes for white children raised in low- versus high-income families grew by 28 percent, from $10,383 for those born in 1978 to $13,202 for those born in 1992 (Figure above).

For Black children, incomes in adulthood increased across all parental income levels. As a result, Black-white race gaps in economic mobility shrank. The gap in average household incomes between white and Black children raised in low-income families fell by 27 percent, from $12,994 for children born in 1978 to $9,521 for children born in 1992 (Figure above).

The Black-white mobility gap narrowed primarily because of changes in children’s chances of moving out of poverty rather than their chances of reaching the upper class. Black children born in 1978 to families in the bottom income quintile were 14.7 percentage points more likely to remain in the bottom quintile than their white counterparts. By the 1992 birth cohort, this gap shrank to 4.1 percentage points—a remarkable 72 percent reduction in the racial gap in the intergenerational persistence of poverty over just 15 years. By contrast, there was no change in Black or white children’s chances of reaching the top fifth of the income distribution conditional on starting in a low-income family.

In non-academic language, these findings show how things have improved for low-income black children over the past few decades in terms of earnings while things have gotten worse for low-income white kids. Although white children continue to do better than black ones on average, and rich children of all stripes continue to do well, both groups of low-income kids are unlikely to make it into the upper ranks of earners later in life—a stinging indictment of the American Dream as commonly understood.

The party narratives favoring one side of this divide over the other cannot handle the complexities of economic mobility in America. For starters, none of this is set in stone and things can be done to improve situations for all kids regardless of their racial or ethnic background. But this requires a real focus on local communities and divergent social contexts rather than one-size fits all approaches favored by the national parties.

Steady work and good jobs for adults is a crucial component of economic mobility for young people as Chetty and his colleagues discovered:

The differences in economic mobility by race and class resulted from changes within the neighborhood where children grew up rather than individual family characteristics. Changes in children’s outcomes were highly correlated with changes in parental employment rates in their community (defined by race, class, and county), even when their own parents’ employment status was held constant. This connection between employment in the prior generation and children’s outcomes closely echoes the ethnographic research of sociologist William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears. For example…the outcomes of white children with low-income parents deteriorated in areas where employment rates for low-income white parents fell the most. Black children who grew up in counties where employment rates for Black parents increased had better outcomes.

Employment rates are only one proxy for community-level change that significantly predicts changes in economic mobility—trends in mobility are also highly correlated with changes in other community-level characteristics, including marriage and mortality rates.

Again, in plain language, communities where adults have good jobs tend to produce more stable families and safer environments with better schools, lower crime, and generally better living standards with more economic opportunities. Kids in these nurturing areas grow up surrounded by employed adults who model good work and individual behavior, and later in life, they can benefit from strong social networks as they pursue their own paths to employment. A lot of these kids end up doing better than their parents in terms of income.

In contrast, kids growing up in communities with lots of unemployed or underemployed adults suffer the consequences of the lack of work through deteriorating families, diminished learning environments, higher crime and more drug problems, and less supportive social contexts. A lot of these kids end up in a worse spot than their parents in terms of future income.

The authors describe how these different scenarios have played out in two metro contexts with similar demographic profiles and starting mobility positions:

Charlotte, NC and Atlanta, GA—two rapidly growing cities in the Southeast—both had low levels of mobility for children born in 1978, particularly for Black children from low-income families. By 1992, mobility improved substantially in Charlotte, nearly reaching the national average due to improved outcomes for low-income Black residents and stable outcomes for low-income white residents. In contrast, mobility remained low in Atlanta for both groups.

Grand Rapids, MI and Milwaukee, WI—two Rust Belt cities—both had low rates of upward mobility for children born in 1978. By 1992, mobility in Milwaukee declined even further with decreases in mobility for low-income children across all race groups. In contrast, mobility in Grand Rapids rose above the national average, driven by substantive gains in mobility for both low-income Black and white children.

Rather than working to help those in need across the country, the two political parties often ignore the complex reality described in this study and bicker over which group of low-income Americans from which regions, states, or localities should be favored over others, if at all.

A country genuinely committed to helping all low-income kids get ahead—and not just the ones pursued by the respective political parties for coalition purposes—would instead focus policies on improving communities across divergent urban and rural contexts that face similar challenges with concentrated poverty and lack of employment.

Economic mobility for low-income children requires living environments with plenty of good jobs for working-age adults; stable families; solid schools; accessible transportation and health care; clean and safe neighborhoods; and thriving local businesses and job networks. We need these supportive conditions for low-income children of all racial and ethnic backgrounds across all 50 states—in small towns and big cities, alike.

Too bad neither party seems ready or willing to adjust its ideological approach to better serve all Americans and pursue these place-based approaches in both urban and rural areas. A political party genuinely committed to economic mobility for all people—and localized policies to promote these opportunities—would deserve sustained majority status in federal and state elections.

Which candidate is likelier to provided the law, order, and jobs necessary to help our poorest? The one who wants more business regulations or less? The one who wants to defund police or support them? Believe your lyin' eyes.

Aside from “affirmative action” policies targeted mainly to blacks over the past 50 years or so, most of the policies intended to reduce poverty have been appropriately colorblind and based on income. Going forward, as a centrist I would support (a) more progressive taxes at the state and local levels, (b) increased emphasis on education in PRACTICAL skills not requiring 4 years or more of college, and (c) federal funding of local facilities to provide basic shelter to homeless people. But I don’t trust woke Democrats to support such policies in a way that is fiscally responsible and truly colorblind. For them, enough is never enough, until the impossible goal of total equality in every facet of society is achieved.