The Ticking Time Bomb in Democrats’ Blue Wall States

The party’s performance in urban areas has been underwhelming in recent cycles, and it could cost them in future elections.

Democrats were understandably relieved—if not thrilled—with the results of last year’s midterms. While conventional wisdom suggested they might lose seats up and down the ballot to Republicans, they held their own in hotly contested races for Congress, statewide constitutional offices, and state legislatures. This included marquee races in battleground states like Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, which collectively make up the party’s “Blue Wall” in presidential elections.

However, those results obscured a nagging problem for the party. In general elections since 2012, when President Obama won his second term, Democrats have not been quite as dominant in those three states’ major urban areas: Detroit, Philadelphia, and Milwaukee. These cities are vote-rich, home to large black populations, and deeply Democratic, but the party’s candidates have mostly underperformed Obama in them while voter turnout there has simultaneously lagged.

This has left Democrats precariously positioned in states with a history of close statewide elections—especially at the presidential level.1 Combined with the significant rightward swing among non-college white voters, Hillary Clinton’s lackluster performance with black voters was the death knell. In Michigan and Wisconsin, she lost ground from Obama across both states, but especially surprising was her underperformance in Detroit and Milwaukee. After Obama won Detroit with at least 97 percent in both of his elections, Clinton earned 95.3 percent there. In Milwaukee, she won 76.6 percent, trailing Obama’s 79.3 percent in 2012.

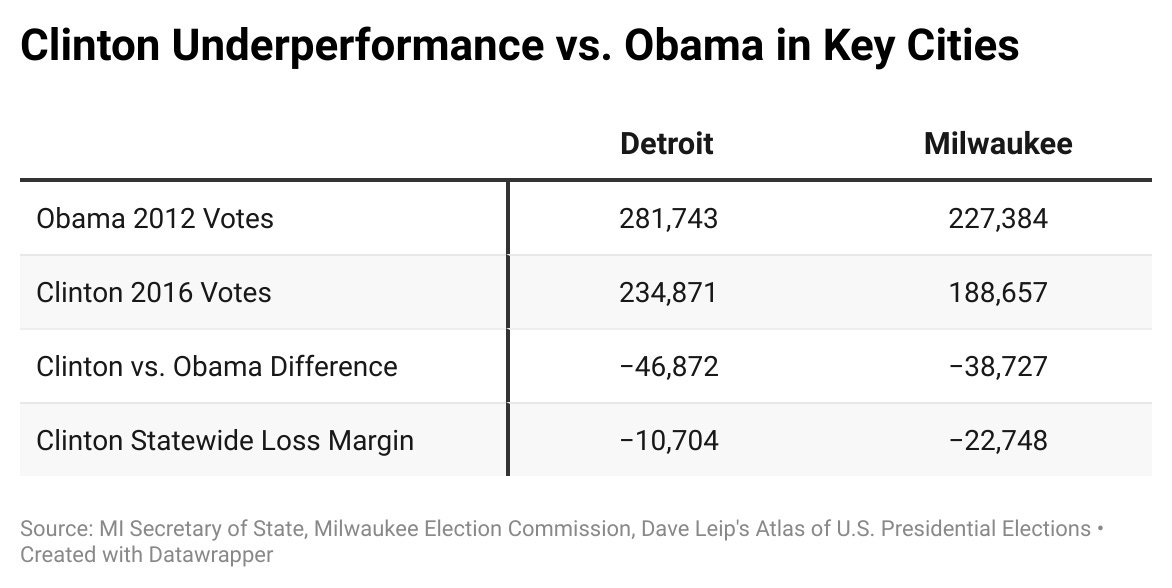

While these slides may seem modest, they turned out to be decisive. In Michigan, Clinton lost to Trump by just 10,704 votes statewide while falling 46,872 votes shy of Obama’s vote total in Detroit. In the Badger State, Trump won by 22,748 votes while Clinton trailed Obama in Milwaukee by 38,727 votes. Had Clinton matched Obama’s vote totals in these two cities, she wins those states.

So, after 2016, it was clear that Democrats’ trouble with black voters in urban parts of Michigan and Wisconsin had hindered their statewide viability.2 However, something else happened in the years following Trump’s victory. Demographic changes in the two parties’ coalitions (which were already underway before 2016) accelerated. Around the country, suburban white voters who were more affluent and better educated swung toward Democrats in the 2018 midterm elections, and the party appeared to make up some lost ground with white working-class and exurban/rural voters as well. In the three Blue Wall states, these shifts helped propel Democratic candidates like Gretchen Whitmer (Michigan), Tom Wolf (Pennsylvania), and Tony Evers (Wisconsin) to victory in key gubernatorial contests.

What was less remarked upon that cycle was the fact that the party again struggled to regain its footing in urban areas. For example, Whitmer won statewide in Michigan by 9.5 points while underperforming Clinton in Detroit. Similarly, in Wisconsin, Evers flipped the state back but did not rebound to Obama’s levels of support in Milwaukee. (Wolf did outperform Clinton in Philadelphia, though he won statewide by a whopping 17.1 points and ran ahead of her in all other counties as well.)

Moreover, even as turnout in 2018 hit historic highs nationally and in each of these three states, it was below-average-to-abysmal in the trio of urban Blue Wall cities. In Michigan, Detroit’s turnout as a share of 2016 votes cast was 78.1 percent, which was lower than every single county in the state. Similarly, Philadelphia’s turnout versus 2016 was 78.3 percent, tied for the eighth-lowest among all Pennsylvania counties. Things weren’t quite as bad in Milwaukee (where turnout was 87.4 percent of the 2016 votes), but compared to all Wisconsin counties, it was still in the bottom half.

These trends have continued in subsequent elections, too. In 2020, Joe Biden flipped all three Blue Wall states, but his performance in the major cities left a lot to be desired. He won Detroit by an astounding 88.9 points, but this was down from Clinton’s 92.2-point margin and Obama’s 95.5-point margin.3 Similarly, in Philadelphia, Biden won by 63.3 points after Clinton carried it by 67.0 and Obama by 71.2. Biden did do one point better than Clinton in Milwaukee, but he still fell slightly short of hitting Obama’s 2012 margin there. And while turnout in Milwaukee was slightly higher in 2020 (78.5 percent) than in 2016 (75.5 percent), it was still significantly below 2012 levels (87.2 percent).

The turnout trendlines were perhaps most alarming in 2022. Compared to presidential votes cast in 2020, Detroit, Philadelphia, and Milwaukee experienced lower relative turnout rates than all counties in their respective states. In Philly, specifically, Democrats’ performance has also steadily declined, as their gubernatorial margins have gone from 76.0 points (2014) to 75.8 (2018) to 72.2 (2022). In fact, while Democrat Josh Shapiro routed Republican Doug Mastriano in the 2022 midterms, Mastriano actually earned more votes in the City of Brotherly Love than 2018 GOP nominee Scott Wagner, despite there being about 56,000 fewer votes cast there this time.

So, this begs the question: if Democrats are finding success despite falling short in these urban areas in both performance and turnout relative to Obama, what’s the big deal? Haven’t they just found a new path to victory? There are two potential problems with this thinking.

First, these urban trends have already hindered one prominent Democrat in a high-profile, statewide election: Wisconsin Senate candidate Mandela Barnes. Turnout in Milwaukee last year was 61.8 percent, the city’s lowest rate of the past decade among both presidential and midterm elections. This undoubtedly struck a blow to Barnes’ chances. While he carried Milwaukee over Republican incumbent Ron Johnson by a huge margin, 80.6 percent to 19.2 percent, raw turnout in the city fell by nearly 36,000 votes from 2018—Barnes ultimately lost statewide by just 26,718 votes. If Milwaukee turnout had mirrored 2018 levels and Barnes had matched Democratic Senator Tammy Baldwin’s performance from that cycle, he would have defeated Johnson by 894 votes.

The second reason urban areas still matter is that they remain massive troves of reliable votes for Democrats that their candidates can tap into—even Detroit and Milwaukee, whose populations have declined in recent years—and, at minimum, offset losses elsewhere. During the Trump/MAGA era, the party has been able to rely on support from more suburban areas, which have swung leftward, but it is unclear how much those shifts will stick in the years ahead. Indeed, we saw evidence in both the 2021 fall elections and last year’s midterms that Republicans have regained some ground in suburban America, especially in places where they ran less extreme candidates. If the GOP eventually frees itself from the grip of Trump and the MAGA faction—a tall order, no doubt—there is no guarantee the gains Democrats have made in these more moderate areas will stick.

Democrats’ struggles in these three heavily black urban areas are a microcosm of national trends: their margins with black voters have steadily declined from 93 points in 2012 to approximately 69 points in 2022, while their advantage among non-white urban voters went from 71 points to about 47 points.4 This period notably coincided with a very clear leftward shift among Democrats on racial justice issues.

However, there is evidence that the party—driven by a growing white, college-educated bloc that has amassed more influence in recent years—may have gotten out ahead of even black people on some key issues, and that taking strong progressive stances on those issues has not necessarily generated more enthusiasm. Barnes, the only recent top-of-the-ticket Democrat in a Blue Wall state to lose his contest, supported calls to defund police departments and eliminate cash bail, even as the city of Milwaukee experienced the most dramatic homicide spike among 29 major cities over the previous year. Despite his campaign’s concerted focus on boosting black voter participation in Milwaukee in 2022, the city’s turnout was ultimately even lower than in the historically lethargic 2014 midterms (when it was 65.7 percent).

Of course, Democrats still win black voters nationally and in these states by overwhelming margins, but the party cannot afford to overlook its recent decline with them (or, for that matter, other minority groups like Hispanics and Asians). The Electoral College and control of the U.S. Senate in 2024 both hinge on how Democrats perform in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Certainly, any further bleeding of votes from non-college-educated white Americans could make it extremely difficult for Biden and Democratic Senate candidates to win these states, and bouncing back from 2022 lows to at least hit the president’s 2020 margins with them will be imperative for their chances. But figuring out how to talk to black voters, especially those in urban areas, about issues they actually care about, such as education, jobs, poverty, and crime, may be just as vital.

These trends have also been present in other major Rust Belt cities, including Chicago and Cleveland, though their home states (Illinois and Ohio, respectively) are typically less competitive at the statewide level than the three Blue Wall states.

The story was a little more complicated in Pennsylvania. Clinton lost statewide by 44,292 votes, but she only underperformed Obama in Philadelphia by about 5,000 votes and actually outperformed him in Pittsburgh by around 4,000 votes—a sign that urban turnout was not the main driver of her loss there.

Meanwhile, Trump actually improved on his 2016 performance in Detroit, jumping from 7,682 votes (or 3.1 percent) to 12,889 (or 5.0 percent).