The Rise of the Neither Party

An increasing number of Americans don't trust Democrats or Republicans on the major issues facing the country. The two parties might want to figure out why.

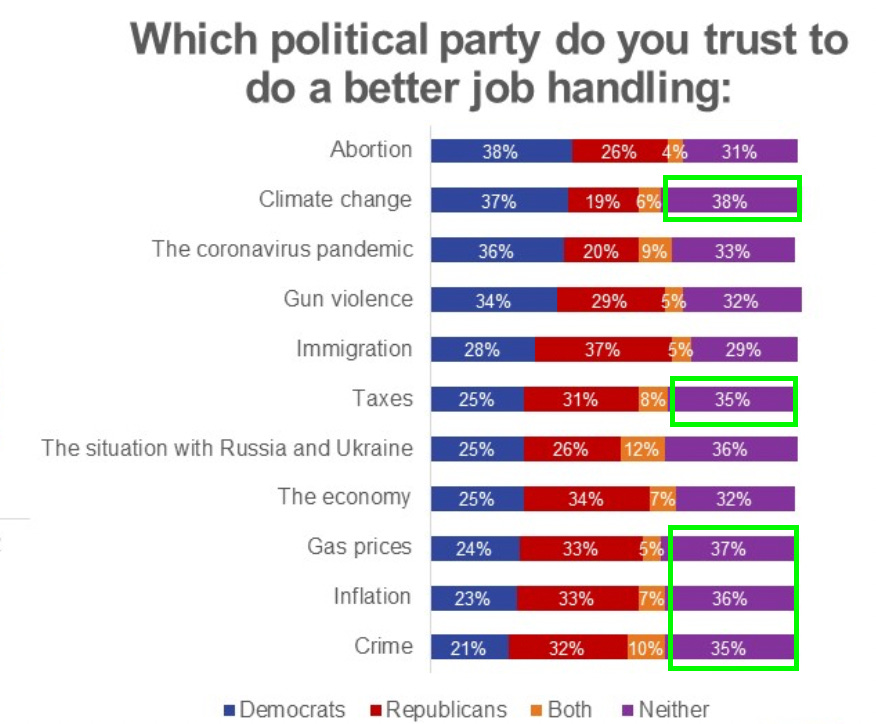

On the eve of the Senate passage of the Democrats’ big reconciliation bill, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), an ABC News/Ipsos tracking poll found that pluralities of Americans trusted neither party to do a better job handling taxes, inflation, and climate change—three of the major components of the IRA. Pluralities of Americans also distrusted both parties on key issues like crime and gas prices. Among unaffiliated voters, the results were even starker: Ipsos reports that nearly half of self-identified Independents say they trust neither party to do a better job handling every issue examined in the poll.

Despite grinding political battles and hundreds of millions of dollars spent on campaigns and outreach over the past few election cycles, Democrats only have a noticeable advantage on the issue of abortion while Republicans only have a noticeable advantage on immigration in this poll. And these leads are not that impressive—less than 4 in 10 Americans trust Democrats and Republicans, respectively, to better handle their strongest culture war issues even with the Supreme Court’s recent overturning of Roe v. Wade and the perceived “invasion” at the southern border.

On nearly every major issue facing the country, an undefined “neither” party holds its own or beats both Democrats and Republicans by small margins.

Why does this matter? Despite the clear evidence of disengagement and distrust among Americans, few elites in either party seem to pay much attention to this development or even study why huge numbers of Americans are rejecting their approaches to major issues. Instead, both sides push base mobilization fallacies and focus on turnout and partisan feedback loops to eke out narrow victories rather than developing sustained efforts to better understand and appeal to increasingly independent voters in America.

Yet neither party has the luxury of taking this approach given larger trends in politics.

Gallup just released three decades of trend data on partisan identification by generations finding that 52 percent of Millennials now identify as Independents along with 44 percent of Gen Xers. Notably, the percentage of Independent identification among Millennials has increased 10 points since 2002 while Gen X numbers have remained stable over time, challenging the notion that voters become more connected to one party or another as they age as seen with the Boomer and Silent generations. It’s too early to say definitively but it appears as if Gen Z voters are also identifying more as Independents than as partisans.

Given their self-interested desire to win more elections, you would think the rise of political independence among the fastest growing voting blocs in the electorate would lead party elites to figure out why large numbers of people distrust them on the issues and perhaps reconsider their policies and pitches to better match the opinions of a big chunk of Americans. Unfortunately, both sides seem content to just appeal to their own people and pretend more ideologically conflicted or inconsistent voters don’t exist or don’t matter. Heavily gerrymandered congressional districts, closed primaries, and partisan media voices encourage both Democrats and Republicans to look away from this reality.

But restricting a party’s issue appeal only to strong partisans in the ranks makes little sense outside of completely lopsided political environments.

If party elites would instead step out of their partisan and activist bubbles for a moment, they might see a better path forward for reaching more voters and increasing their policy appeal to Independents and other non-aligned Americans. It’s not about cutting the difference with the other side or being a squishy centrist or selling out your principles. A successful strategy for appealing to disenchanted Americans will require both honesty with voters about the complexity of most issues and a willingness to challenge the ideological confines within one’s own party.

Take the issue of crime. You rarely hear any Democratic politician say: “If you commit a violent crime, you’re going to jail for a long time.” Likewise, you rarely hear any Republican say: “We need to fight concentrated poverty and drug addiction in our cities to help reduce crime.” Democrats talk vaguely about reducing gun violence and Republicans talk vaguely about law and order and not much else. Consequently, as the Ipsos poll shows, most Independent voters shrug their shoulders at these limited approaches and don’t really trust either side on crime.

In contrast, a combination of these ideas in a smart manner would better represent where most Independents and unaligned voters land on the issue. Get the bad actors off the streets. Fight the social conditions that lead to violence. Stop the flood of guns into our communities. Respect the police and give them resources. Make sure the criminal justice system treats all people fairly.

This isn’t rocket science. It is mostly common sense and a willingness to challenge—or go around—the limited views that exist within both political parties.

Democrats believe their electoral fortunes and party image will improve through better communication and advertising to “sell the win” on the recently signed Inflation Reduction Act. As new polling from Navigator Research shows, the bill receives solid support from both Democrats and Independents, producing two-thirds support overall, with the health care provisions clearly emerging as the most popular elements of the new legislation. Since Democrats historically do quite well with voters on health care—and Republicans appear to have few if any popular policy proposals of their own heading into the midterms—perhaps success on this front will lift trust in Democrats on other issues in Ipsos’ next tracking polls in September or October. And a series of legislative victories ahead of the midterms will at least bolster the spirits of flagging Democrats and give the party’s candidates insulin price caps for seniors and lower drug costs to run on.

But given the lack of any noticeable increase in trust or support for Democrats following the passage of their massive $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan last year to help deal with the ongoing economic disruptions from the Covid pandemic, it seems doubtful that any partisan policy wins these days will produce widespread, lasting political gains and increased trust on the issues. Voters outside the party bases increasingly don’t buy message campaigns and attempts to oversell the benefits of legislation. As Democrats learned with Obamacare over many years, non-base voters will give parties credit for their policies only when they feel tangible improvements in their own lives and when the other side attempts to take these gains away—not after watching propaganda ads ahead of elections that promise things are going to be better. Republicans faced the same problem with diminishing political returns when they passed their big tax cut legislation under President Trump in 2017.

To reach the increasing numbers of Americans disaffected from politics over the long-term will require three big shifts in strategy from the major parties or any third-party contender: (1) More political imagination to help see the world as unaligned and less ideological voters see it; (2) More political fortitude in resisting narrow party-line demands to help turn this imagination into reality with sensible policy frameworks that draw from diverse perspectives and appeal to multiple types of voters, not just diehard partisans; and (3) More political honesty in leveling with voters about what pragmatic legislation can and cannot achieve on the economy and other issues.

Successful parties in the future must be willing to set aside their ideological commitments from time to time and open their partisan minds to alternative ideas if they want to gain the support of an increasingly unaligned and skeptical electorate. They need to be straightforward about the possibilities and limitations of public policy and admit their mistakes and correct them when things go wrong. The electoral benefits of greater political imagination and ideological flexibility could be massive—but only if the parties are willing to explore more creative models for policy design and political engagement.

As noted political theorist Willy Wonka put it: “If you want to view paradise, simply look around and view it.”