What is industrial policy? From an Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) report:

British economist Ken Warwick, in 2013, broadly defined industrial policy as, “any type of intervention or government policy that attempts to improve the business environment or to alter the structure of economic activity toward sectors, technologies or tasks that are expected to offer better prospects for economic growth or societal welfare than would occur in the absence of such intervention.”

More recently, ITIF President Robert D. Atkinson defined industrial policy as “a set of policies and programs explicitly designed to support specific targeted industries and technologies.” In this sense, there can be industrial policies for a variety of goals. Atkinson argues that the goal should be U.S. international competitiveness, especially in advanced technology sectors.

Others have taken the term “industrial policy” and applied it to expansive social policy goals. Mariana Mazzucato, Rainer Kattel, and Josh Ryan-Collins have advocated “mission-based innovation” as the basis for industrial policy, taking up Warwick’s “societal welfare” element. They identify mainstream, neoclassical economics and its reluctance to employ the power of the state as a cause for societal ills, including growing economic inequality, economic stagnation, a succession of financial crises, and climate change. While others have made these critiques, Muzzucato and colleagues seek to apply technological innovation not only to technological challenges but to societal missions such as reducing economic inequality and building sustainable development. They hold up the Apollo Moonshot project as an organizational model for how to get there.

This suggests that everything the government does to direct the economy into preferred channels—not just a direct governmental role in fostering the technology and development of a particular industry—can be considered industrial policy. This makes industrial policy a term for a country’s overarching national economic strategy, which of course changes drastically over time.

In the beginning, there was the Hamiltonian “American System”, as Henry Clay called it, which included tariffs, physical infrastructure (canals, railroads, telegraph lines) and national banking. It was designed to nurture American manufacturing both by building internal markets and protecting the sector from external competition.

While usually associated with the first half of the 19th century, in truth the system was aggressively built on by Lincoln (who described himself as “an old-line Henry Clay whig”) and his successors. There was a vast expansion of railways, especially the transcontinentals, and telegraphs, increased tariffs, the establishment of a system of national banks, pathbreaking investments in research and organizations to promote public health, the founding of the National Academy of Sciences, the development of mass basic education and the creation of a Department of Agriculture and a system of lang-grant colleges to drive innovation and raise higher education levels.

This version of industrial policy underpinned the advance of the Second Industrial Revolution in America in the last quarter of the 19th century and early 20th century. The country quickly hurtled to the front of the world’s industrial nations, thanks to its vast internal market, developed infrastructure and educated workforce. The Progressive Era arose as an effort to stabilize the outcomes of this economic juggernaut.

Industrial policy developed further, as electrification and the rise of mass production, especially as applied to the automobile, drove US manufacturing forward. The high school movement spread secondary education across the country. A new nationalism arose to join the imperative of national development to the welfare of the ordinary citizen. The federal government took leading roles in the development of aviation and radio (e.g., the Radio Corporation of America).

The next phase of industrial policy was the New Deal on the heels of the Great Depression. Government took a great deal more responsibility for stabilizing the economic system and securing the welfare of citizens, There was an enormous amount of infrastructure development, not only obvious examples like the TVA, but also transportation and communication networks that fed rapid productivity growth in 1930’s and which the World War 2 mobilization built on.

The next phase of industrial policy arrived in the postwar era. Vannevar Bush published his famous 1945 report, The Endless Frontier, which laid the basis for a system of government sponsorship of science and engineering specifically designed to keep the US in the forefront of technology development. The national labs were formed and indirectly supported research organizations like Bell Labs flourished. The Sputnik shock turbocharged this system resulting in the formation of NASA and ARPA (later renamed DARPA). This system supported not just the research but the development, prototyping, testing, demonstration, and often the initial market for a technical advance (“collaborative first customer”)

In addition the period of the late ‘40s through early ‘70s saw a massive surge of public investment in education (GI bill) and infrastructure (interstate highway system). But the whole system comes to a screeching halt with the stagflation of the 1970’s and the Reagan elections of the 1980’s.

The sputtering of the American economic model and rise of competitors like Japan led to the search for a new approach. Some Democrats started to make the argument that America was not properly turning its scientific advances into competitive, commercial products. Therefore there was a need for the government to directly nurture specific industries to ensure the connection between technical innovation and market success and, through that, overall US competitiveness. Other Democrats weren’t so sure. This became known as “the industrial policy debate”, despite the fact that, as noted, the country already had a de facto industrial policy.

But the industrial policy advocates lost the debate, both within the Democratic party and in the overall political discourse. Industrial policy was successfully pilloried as “picking winners and losers” by the ascendant economic philosophy of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism saw the market as the decision maker in economic development; there was no need for a national economic strategy and certainly no need (in fact, it would be harmful) for government to consciously try, through spending or regulations, to develop specific industries or economic sectors. And God forbid there should be any attempt to interfere with the natural flow of free trade to protect or promote any part of the economy.

This philosophy was embraced in the 1990’s and early 2000’s by both Democrats and Republicans. Cracks in neoliberalism appeared with the Great Recession of the 2008-09. The Obama administration did not explicitly embrace industrial policy but the administration and Democrats in general were clearly moving in the direction of more public investment and some conscious attempts at economic intervention (saving the auto industry, promoting green energy). It did not amount however to a clear break with neoliberalism and the formation of a new national economic strategy, a “new American System” as Michael Lind has described it.

With the interregnum of the Trump years, which further broke neoliberalism’s hold on both parties, the Biden administration came in facing dual public health and economic crises. As Biden had signaled during the campaign (and assured the left of his party) he was prepared to go big to solve these crises up to and including fundamentally restructuring the US economy through a vast expansion of government spending and interventions.

And they duly attempted to do so, despite their razor thin Congressional margins. Leaving aside the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, the administration proposed $4.37 trillion in new spending to transform the country. They eventually got $1.45 trillion in spending through three large bills: the bipartisan infrastructure bill, the CHIPS and Science Act and the so-called Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

The administration is on record as embracing industrial policy, though they typically call it “industrial strategy”. Here’s Brian Deese, Biden’s Director of the National Economic Council, from June of 2021, where, among other things he name-checks the American System and the post-WWII system of technology promotion as models for what the administration is seeking to do:

I am excited to lay out our vision for a twenty-first century American industrial strategy—a strategy to strengthen our supply chains and rebuild our industrial base, across sectors, technologies, and regions….

We should be clear-eyed that the idea of an open, free-market global economy ignores the reality that China and other countries are playing by a different set of rules. Strategic public investment to shelter and grow champion industries is a reality of the twenty-first century economy. We cannot ignore or wish this away.

That’s why we need a new strategy. An industrial strategy for the second quarter of the twenty-first century. One that draws from the best lessons of the past, but leans into the challenges of the future. This strategy is built on five core pillars: supply chain resilience, targeted public investment, public procurement, climate resilience, and equity.”

This description is a bit of a dog’s breakfast of different ideas and priorities. And so it has come across to most Americans. Voters certainly got the idea that the Democrats wanted to spend a gazillion dollars on dozens of programs in the midst of a 40 year inflationary high (some of which was driven by American Rescue Plan spending), but the purpose of this spending—that “new industrial strategy” spoken of by Deese—has not been so clear.

Voter knowledge is remarkably low about the infrastructure and CHIPS and Science bills. By the time the former passed it had been obscured by six months of Democratic in-fighting on a much larger spending package to which the infrastructure bill had been held hostage. To put it mildly, that didn’t help voter awareness. It seems likely the clearest economic strategy priority most voters heard about was the Democrats’ ardent commitment to climate action.

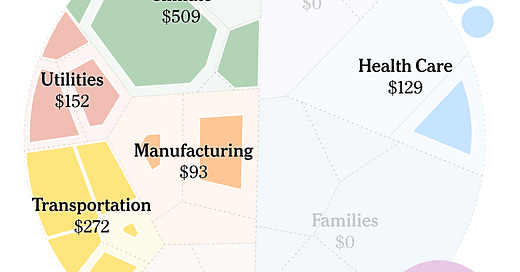

This commitment is evident in the division of spending across the three bills, in which climate looms quite large (New York Times analysis):

To be sure, there are commitments in these bills, including the IRA, that may prove helpful in promoting sectors like manufacturing. For example, following the CHIPS act, some major semiconductor companies say they will build new chip factories in the US. And subsidies and regulations in the IRA are leading some carmakers and battery manufacturers to increase investment in the US.

But the fact remains that a clean energy transition is a slender reed upon which to build a national economic strategy. Public aversion to energy price spikes and unreliability will bedevil this transition unless managed carefully. This will prove difficult to do because of the political pressure and concrete incentives, as in the new bills, to rapidly ramp up use of renewables and electric cars. This corresponds to what Democratic elites want, who are ideologically committed to this path, but not ordinary voters.

A national economic strategy worthy of the name would not be so reliant on a green energy-centered path, which is challenged both substantively and in terms of political popularity. Of course, the “Green New Deal” theory is that clean energy by itself can power a national economic transition and dramatically increase the availability of good jobs, including in left-behind areas. This is a fantasy. As Noam Scheiber has shown, there will definitely be some jobs created but they will not necessarily be good ones in the America of today (as opposed to some green utopia).

A serious national economic strategy or industrial policy would grapple with the broader technological transition the US is going through and the challenges that new levels of automation, roboticization and AI, not to mention the rise of China, are going to present for ordinary workers, especially those without a college education. Directing economic development so that the adoption of new technologies enhances rather than degrades workers’ lives is the true test of a national economic strategy. This will require a more active role, on everything from research to government procurement to quid pro quos from business, than is currently envisioned by Democrats.

The Biden administration, while it has commendably departed from the neoliberalism of the early 21st century, is still very far from a national economic strategy—a “new American System”—that would work substantively or generate broad support from American workers (and the two are related of course). It is not enough to reject neoliberalism. You must have an effective replacement.