The Great Awokening of Higher Ed Has Ended—But Is It Too Late?

Growing numbers of Americans prefer sticks over carrots to move colleges and universities towards reform—a crisis we in academia largely brought upon ourselves

According to many right-aligned narratives, contemporary colleges and universities dedicate themselves primarily to converting normie students into aggressive social justice warriors. Course materials are little more than left-wing propaganda, and those who diverge from the preferred narrative are punished or expelled. Only the strong hand of the state can get these institutions under control and focused on their primary mission of producing and disseminating reliable empirical knowledge.

These narratives are false.

They’re nonetheless scaffolded by some important truths. University faculty are indeed highly unrepresentative of America as a whole, and they’ve become less representative over time in many important respects. This does not tend to affect student grades—students are generally not punished by professors for failing to parrot the preferred ideological lines—but the skew of the professoriate nonetheless does influence the curriculum and campus climate in real ways.

Likewise, students and faculty can and often do publicly dissent from prevailing narratives, but they often face social sanctions when they do so. Rather than serving as bastions of free exchange of ideas or rollicking debate, most campuses remain significantly more inhibited expressive environments than most other places in society—and have only grown less free in recent decades.

Aspirants who decline to color within the lines can still get admitted to grad school or hired and promoted as faculty (case in point!), but there is evidence that they often face discrimination in committees and as a result often get placed lower on the prestige totem-pole than their comparably qualified peers.

Work that diverges from institutionally-dominant views can be published. It often faces bigger hurdles with respect to institutional review boards, peer review, and garnering citations from other academics, while work that is useful for advancing the preferred narrative often faces insufficient scrutiny. What’s more, there are sometimes politicized calls for retraction when inconvenient findings are published. Meanwhile, there are demonstrable systematic biases published social scientific research analyzing the types of people who are less present in colleges and universities—i.e., the poor and working class, devoutly religious people, rural folks, and Trump voters, among others.

These are very real problems. They undermine the quality and impact of teaching and research. However, they are also longstanding structural issues. The kinds of policies advocated by Republicans today—such as slashing university budgets or banning Critical Race Theory, Gender Studies, and DEI programming—would do precisely nothing to address any of the problems described above. Proposed bids to eliminate or weaken tenure protections would probably make many of these problems worse.

The good news is that prior to and completely independent of these GOP-led measures, higher ed seems to have turned a corner.

Universities Have Passed “Peak Woke”

Alongside most other knowledge producing institutions, colleges and universities transformed dramatically after 2010.

There was a significant uptick in student protests after 2011, for instance. It escalated in the fall of 2014 as protests against police violence against African Americans gained in strength and reached a crescendo following the election of Donald Trump. But it wasn’t just protests. Invited speakers were prevented from giving their talks. Professors were prevented from teaching their courses, or were harassed for engaging in extramural speech that students didn’t like. Those who crossed student activists were sometimes driven from campus altogether. At least one professor committed suicide after being cancelled.

It wasn’t just students who grew more radical, though. Faculty and administrators got in on the action, too.

Alongside the student unrest came significant changes in institutional structure and culture. There was a rapid growth in university administrators who often sought to justify their roles by meddling in research and teaching, imposing and enforcing myriad new restrictions on what people could do and say on campus, and significantly undermining academic freedom and faculty governance in the process.

Sex bureaucracies surveilling and policing sexual relations between consenting adults proliferated, often punishing people with little evidence or due process. Bias Response Teams sprouted up, allowing people to anonymously spur investigations against anyone without any substantiation at all. Faculty and students began hijacking these apparatuses to sink competitors, punish exes, settle personal vendettas, and much else besides.

Professors also became much more political, with their research increasingly focused on highly contentious topics like race, gender, sexuality, inequality, and political elections—often with the explicit goal of supporting social justice movements like Black Lives Matter and #MeToo or taking part in the #Resistance against Trump and the Republican Party. They began writing and speaking to the public more as professors in support of their preferred moral and political goals. They also engaged in growing activism as professors, perhaps most dramatically in the case of the 2017 March for Science whose main discernable effect on society was to dramatically reduce public trust in scientists just before the outset of a major pandemic.

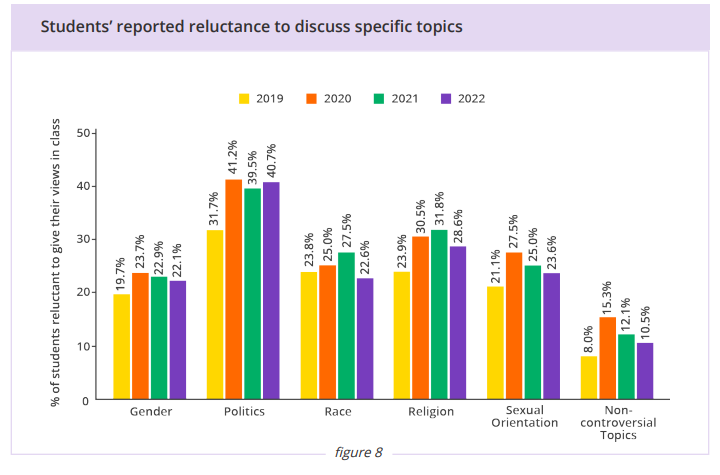

However, a range of empirical data suggest that the post-2010 “Great Awokening” may be winding down. For instance, Heterodox Academy recently released the results of its 2022 Campus Expression Survey. It shows that students today feel more comfortable sharing their perspectives across a range of topics than they did in previous years.

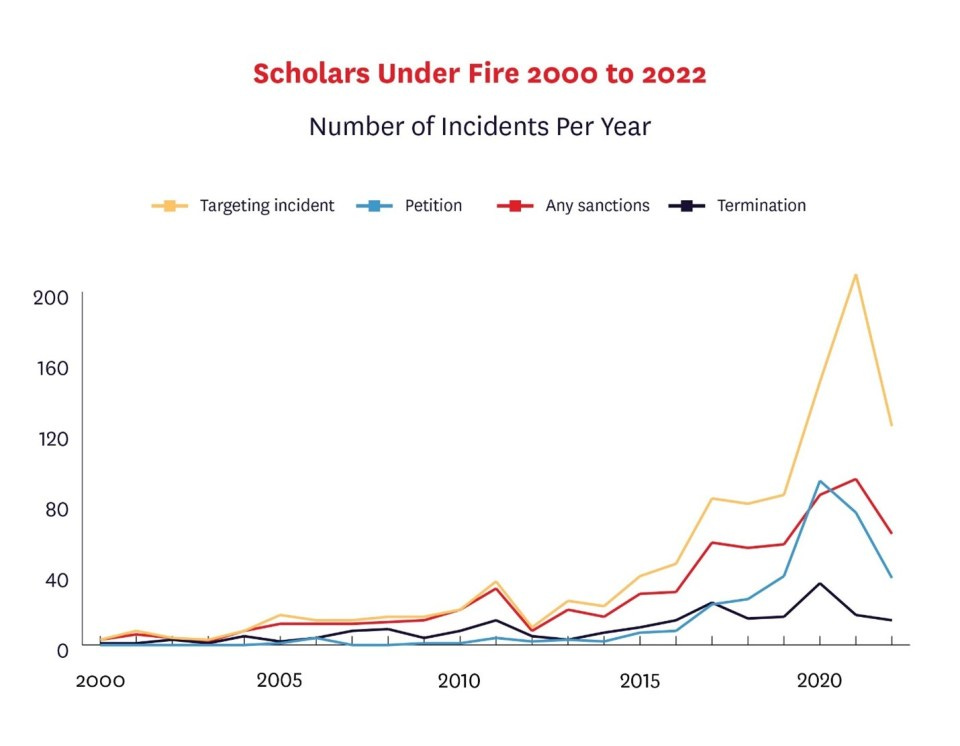

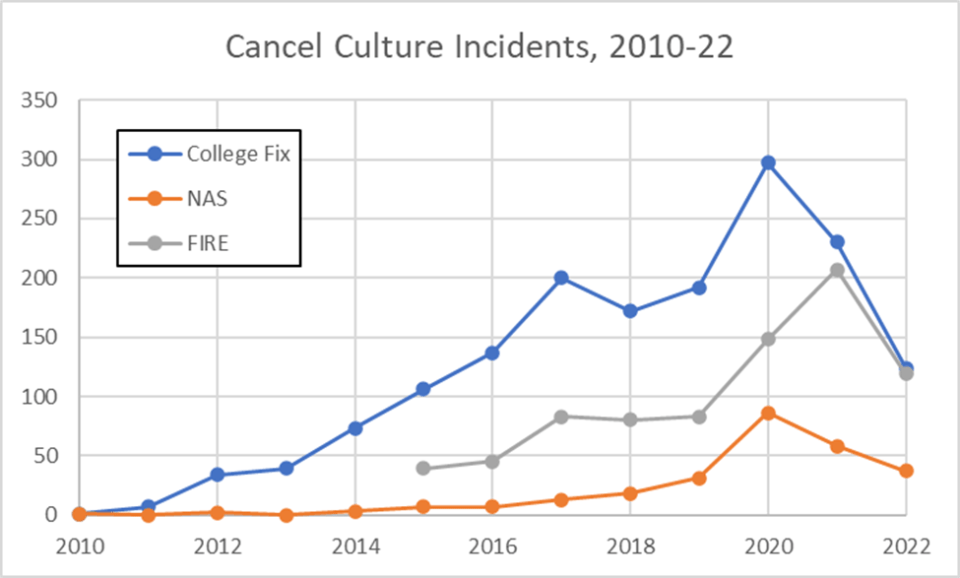

It may be that contemporary students feel less need to self-censor because the objective conditions have changed at colleges and universities. You can see this, for instance, in data on “cancel culture” events. Incident trackers compiled by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) show marked declines in attempts to punish scholars for their speech or views across all measures:

FIRE’s data is not an outlier. We see apparent declines in attempts to censor uncomfortable speech on campus across a range of datasets.

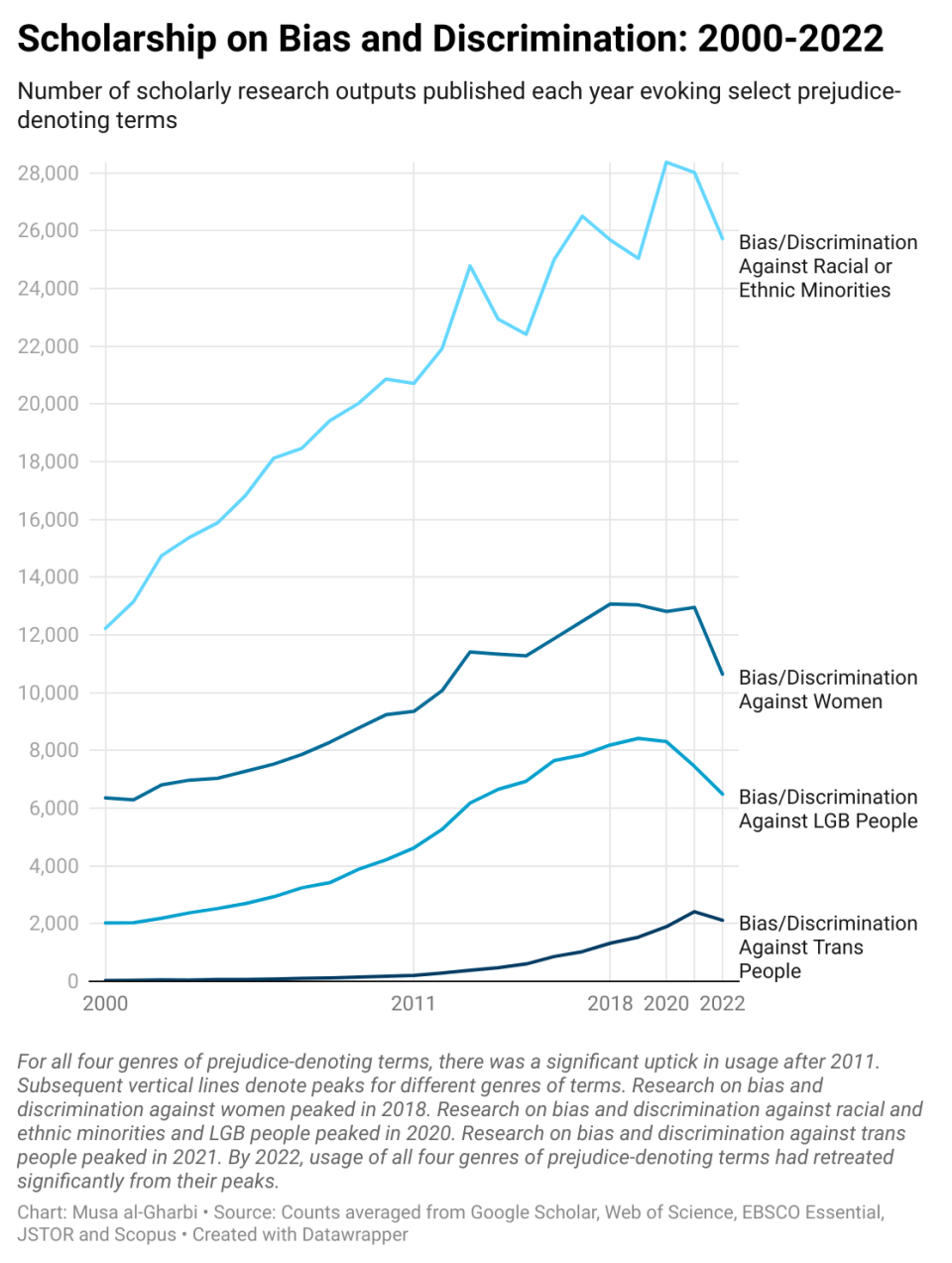

And professors, too, seem like they've calmed down a bit. The intense scholarly focus on identity-based bias and discrimination seems to have cooled, for instance:

College leaders and professors have also become more assertive in pushing back against illiberal policies coming from within campus. There has been trimming of administrative bloat induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, it seems like people on campus started getting their act together just in time to experience a severe backlash from Republican lawmakers and the public writ large.

Not Too Little, Not Too Late

The sociological and ideological distance between academics and the rest of America has always been wide. Since 2010, however, the gulf between highly-educated Americans and everyone else grew much larger—primarily due to asymmetric polarization within the educated class itself. These differences also grew more salient as radicalized professors, students, and college-educated Americans aggressively sought to impose their values and priorities on everyone else and confront, denigrate, marginalize, or sanction those who refused to get with the program.

One core consequence of this radicalization has been reduced public trust in higher ed. Most Republicans today believe that universities, on balance, do more harm than good. A majority of Americans across partisan lines believe higher ed is moving in the wrong direction, and most believe that what they get from attending colleges and universities may not be worth the cost. This is not idle sentiment: enrollment in colleges and universities dropped precipitously during COVID and has not recovered.

The growing distance between academics and everyone else has also significantly eroded trust in science and expertise. Studies in the United States and around the world consistently find that when people do not see folks like themselves reflected in institutions—when they do not have the sense that their values and interests are being meaningfully represented in said institutions or especially if they view them as actively hostile to their priorities and worldviews—the natural impulse is to mistrust, marginalize, and defund those institutions.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, the growing gulf between academia and the rest of society has created an opportunity for Republicans to raise money and win elections by vowing to get colleges, universities, and K-12 schools under control and refocused on the core public services they are supposed to provide on behalf of the voters and taxpayers at whose discretion they ultimately serve. After all, professors and K-12 instructors at public schools are at bottom civil servants—whether they recognize it or not.

Institutions of higher learning began moderating on their own prior to and independent from the ill-conceived proposals now being advanced by Republicans. Nonetheless, it seems likely that the GOP will attempt to take credit for any moderating trends should they continue—and these trends likely will. For the sake of telling the truth and protecting institutional autonomy, it’s important to robustly challenge these Republican narratives.

Colleges and universities are not just capable of reforming themselves; they are already reforming themselves. Positive trends should be recognized, and ongoing efforts should be encouraged and supported.

But doing so would require more in academia and on the left to explicitly admit that there are real problems of bias and parochialism in institutions of higher learning. It undermines our own credibility to dismiss concerns about the culture and operations of educational institutions as an empty moral panic. Ordinary people can see with their own eyes that that’s not the case, and no one will trust us to effectively fix a problem if we won’t even acknowledge it exists. We can’t talk about progress while insisting there’s nothing wrong.

“Nothing to see here” is a non-starter. “There’s something to see here, and it’s a positive trend” is much more promising. Let’s run with that.

Musa al-Gharbi is a sociologist at Columbia University and a senior fellow at the Niskanen Center.