What does American politics look like? There is a widespread view among political scientists and political consultants that the electorate has become inextricably polarized between Democrats and Republicans and there is a very small group of swing voters that decide national and some state elections. Barack Obama's former political advisor David Axelrod told Yascha Mounk recently on his podcast, "There is a less and less sort of moveable vote because party has now become a cultural identity."

My view, based on covering elections and looking at American political history, is that the electorate is becoming, if anything, more fluid and volatile. There are partisan extremes in both parties that espouse consistent ideologies and that often dominate the public discussion of politics—for them party is a cultural identity—but there are growing numbers of voters who are uncomfortable with these extremes and with the parties in so far as they are identified with these extremes. I ordinarily like to leave polls and polling analysis to my co-author Ruy Teixeira, but in this case, there are several polling results that I would cite in favor of my view of the American electorate.

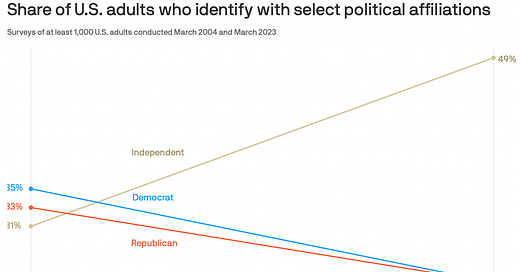

The first is the rise of "independent" voters. Gallup conducts regular surveys that ask respondents: "Do you consider yourself a Republican, a Democrat, or an independent?" As late as January 1, 2008, the percentage of Democrats exceeded that of independents as well as Republicans, but since then, the percentage of independents has been growing at the expense of both parties. In March 2023, it hit an all-time high (since Gallup has been asking the question in 1988) of 49 percent. Republicans and Democrats were tied at 25 percent. Of course, when these independents are asked what party they lean to, Democrats and Republicans split the vote, but that's not the point. The point is that growing percentages of the electorate are alienated from both parties. They might "lean" to one rather than the other, but that is not the same as being hardline partisans that are culturally identified with one party rather than the other. If anything, the cultural identification with the parties is diminishing.

The second poll has been done recently by the Wall Street Journal. It found that if Donald Trump and Joe Biden are the presidential nominees in November 2024, 26 percent of the electorate has not made up its mind whom to vote for. That is more than a slice of the electorate and suggests again that there is a large segment of voters who are not strongly committed to either party or to the political views of the party's candidates. According to the poll, more of these voters identify themselves as "moderate" than either "liberal" or "conservative." A majority support abortion rights. Almost three-fourths of them have unfavorable views of Trump and Biden. They disapprove of Biden's handling of the economy and the border, but they think he is the more likeable and caring of the two candidates, and by a wide margin they think Trump did commit illegal actions after the 2020 election. They are younger and somewhat less white and less-college educated on average than the overall electorate.

Beyond what the Wall Street Journal found, there is no other extensive polling of this group of the larger group of "independents,' but based on these findings and those of The Liberal Patriot, as well as on past election results, I would venture a few generalizations about what, on the average, is their outlook.

First, on social issues, they do not share the views of the radicals in either party on such issues as abortion or immigration. What is "liberal," "conservative," and "moderate" changes by the decade. In 2004, supporting gay marriage was identified with liberals and cost Democratic nominee John Kerry some votes, but by 2016, both Republican and Democratic presidential nominees supported gay marriage. It was a "moderate" position. In 2024, supporting "gender-affirming" medical intervention for minors will be identified with liberals, while banning abortion with the right. Independents and "persuadables"—whom I will hereafter call "the uncommitted"—will on average reject both these positions. Similarly, the uncommitted will reject both open borders (or its functional equivalent), on one side, and mass deportation of illegal immigrants, on the other.

Second, on economics, the uncommitted center appears to support Social Security and Medicare, food stamps, and the minimum wage—all programs that are either universal in the case of the the two big entitlement programs, or don't require large government expenditures relative to the overall budget, in the case of the latter examples. They share with conservative Republicans a distrust of "big government” but they have rejected Republican and conservative efforts to ax social spending or reward big business and the wealthy. If candidates can show their opponents are on the side of the rich and big business, they are likely to win over the uncommitted.

Third, on foreign policy, they are skeptical of any initiatives that do not appear obviously based on defending the national interest and American security. In The Liberal Patriot poll, large numbers of the young—ranging from Zoomers through Millennials—say "neither party is close to my views" on "taking on China in a smart manner" or "maintaining a strong military and defense." In so far as the "persuadables" are heavily represented among this same age-range, I think it is fair to conclude that an aggressive foreign policy aimed at making the world safe for democracy would be a hard sell among them. Support for Ukraine war spending, for instance, is likely to waver among many of these voters as time goes on with some supporting and some opposing.

Finally, what conclusions can one draw about who the uncommitted would back in November 2024? Let's assume that Biden and Trump are the nominees. On economics, Biden seems to have received little credit for his signature achievements, including the Inflation Reduction Act or the CHIPS and Science Act. The results of these bills are yet to be seen, and in the next year, continued inflation may overshadow them. The Fed's actions may also finally cause a slowdown. Biden will also have to contend with the rise in illegal immigration during his administration. Trump will try to distance himself from his party's extreme views on abortion, but he will have difficulty doing so. If the election were merely decided on the candidates' platforms, Trump could enjoy a slight edge.

But the election is likely to pivot on factors that are unique to 2024. These include Biden's age and physical fitness for office; Trump's character and integrity; and the electorates' sense of what the candidates really care about. Trump is likely to suffer on the last two measures. By November 2024, Trump could be a convicted felon. At the least, his indictments will loom large. As the Wall Street Journal poll showed, the persuadables believe that Trump acted illegally.

In the 2016 election, Trump, facing Hillary Clinton, was able to convince the uncommitted that he cared more about them than his opponent did, but by 2020 election, Trump's vast egotism had undermined his promise of care and concern. Since the 2020 election, Trump's self-concern has, if anything, become all-consuming, as evidenced in his refusal to get beyond his grievances about the 2020 results. Biden may appear feeble, but as the Wall Street Journal poll showed, he significantly exceeds Trump when these voters are asked whether the candidate "cares about you." That single consideration is often decisive in American elections—it won Obama Ohio in 2012—and it could prove decisive in 2024.

As for the general nature of the electorate, political scientists and consultants would be wise to junk theories about a polarized electorate. Yes, it is polarized at the ideological extremes, and because of the perversity of our primary system and political gerrymandering, those extremes are disproportionately represented in some state houses and in the House of Representatives. But many voters find themselves unrepresented by these extremes and for that reason no longer identify with either party.

Democrats may think that the current chaos wrought in the House of Representatives by Republican Matt Gaetz and his followers will boost their numbers, but I suspect that it will do more to increase the ranks of the disillusioned and uncommitted. As Gallup surveys have shown, the percentage of voters who cite "government" as their primary concern entered the top four after 2008 just as the number of independents began to soar.

Winning over the uncommitted, and creating a majority that includes them, will require reforming our electoral system and developing a politics that speaks to their concerns—neither of which are on the horizon today.

John B. Judis is author of The Politics of Our Time: Populism, Nationalism, Socialism and, with Ruy Teixeira, of the forthcoming Where Have All the Democrats Gone?