The Democrats’ Long Goodbye to the Working Class

This year’s realignment was decades in the making.

As we continue to sort through the wreckage of the 2024 election, one thing has become very clear: Donald Trump gained ground relative to 2020 in almost every state and with almost every demographic group. Even the most reliably Democratic constituencies, including racial minorities, shifted in his direction, an ominous sign that the party’s coalition may not be as solid as they once thought. Indeed, these results shone a spotlight on long-festering problems in the Democrats’ coalition, which have left them a shell of their former selves—as the party not of the multiracial working class but increasingly of society’s elites.

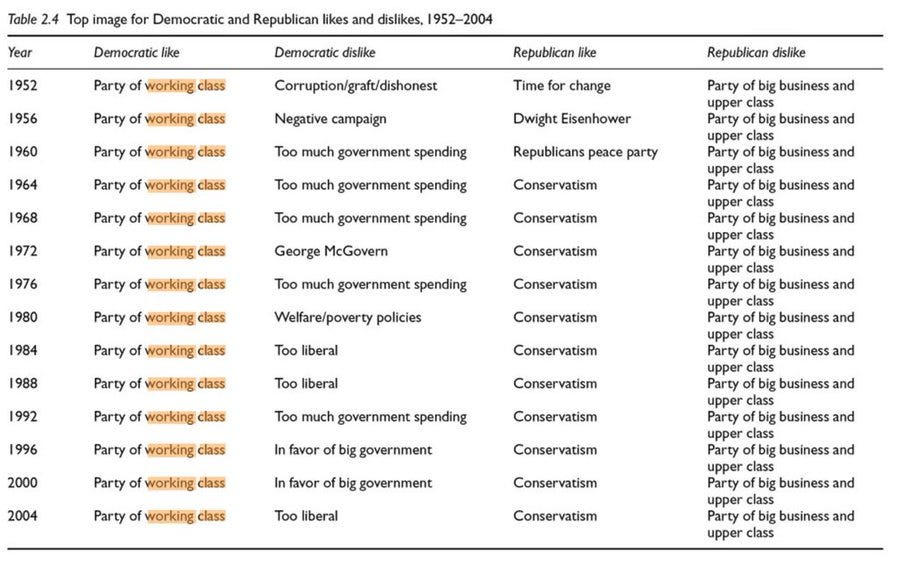

Though it may be hard to believe this fate has befallen the party of FDR, these changes didn’t happen overnight. Democrats were long considered by many Americans to be the party of the common man and woman. Mark Brewer, of the University of Maine, has found that in every presidential election between 1952 and 2004, the trait voters said they most liked about the Democrats was that they were “the party of the working class.” By contrast, the biggest mark against the Republicans was that they were viewed as the party of big business and the upper class.

These perceptions created a clear divide between the parties’ coalitions during that period: Democrats were likelier to win lower-educated and lower-income voters while Republicans were the favored party of many college-educated and affluent Americans.

At the same time, the parties had also begun to polarize along racial lines. Following the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and 1965 Voting Rights Act under President Lyndon Johnson, black Americans almost uniformly threw their weight behind Democrats while white voters—especially working-class, white southerners—began a slow but inexorable slide toward Republicans. For a time, this realignment came at the expense of the Democrats: from 1968 through 1988, they won the presidency just once, in 1976.

However, by the 1990s, the country was growing more diverse and better educated. Bill Clinton was a beneficiary of this new reality, as he made sweeping gains with women, young people, voters of color (especially Hispanics), and college-educated voters. Importantly, he also retained significant support from white Americans and lower-educated voters, who made up the vast majority of the electorate. As Clinton rode this coalition to victory twice—marking the first time since FDR that a Democrat had won two full terms as president—some political observers, including my colleague, Ruy Teixeira, saw the emergence of a new majority, one that could consistently win elections using the formula Clinton had used.

In 2008, Barack Obama built on the Clinton coalition, bringing in even higher levels of support from almost every major party constituency, including blacks, Hispanics, Asians, young people, and women.1 He also notably became the first Democratic nominee since at least 1988 to decisively win voters who held a bachelor’s degree and fared far better with high-income earners than past Democrats had. These were the first signs of a growing professional class whose cultural values had aligned many of them with Team Blue—a departure from the past.

Obama’s two wins confirmed for many Democrats and Republicans the validity of the “emerging Democratic majority” thesis. Gone were the days when Democrats needed to win a majority of white voters, a feat they had found nearly impossible to achieve since the 1960s. Now, the party that represented America’s demographic future stood to lead it as well.2

But no sooner had that consensus come into focus than Donald Trump arrived on the scene. Trump disrupted the Democrats’ plans for building a dominant coalition and, in the process, helped precipitate a dramatic realignment between the two parties—one rooted in economic and social class. This change has tipped the demographic advantage in favor of Republicans and left Democrats at very real risk of losing many of the voters who not long ago were expected to deliver them an enduring majority.

In 2016, non-college-educated voters, a group that had backed Obama by four points in 2012, swung to Trump, who won them by six. This was a core driver of Trump’s win, as these voters made up a whopping 63 percent of the electorate that year. Meanwhile, Hillary Clinton gained substantial ground with college graduates, who went from also backing Obama by four points to supporting her by 15—an early sign that Democrats would struggle to win at the national level without a critical mass of working-class voters behind them.

Four years later, as Joe Biden defeated Trump, the education gap grew even wider. Biden improved on Clinton’s advantage with college-educated voters by three more points, while Trump’s margin with non-college voters remained virtually unchanged—likely the difference in the outcome. Even in Biden’s victory, though, there were signs that the traditional Democratic coalition wasn’t holding. The clearest example was the rightward swing of Hispanic voters, who had backed Clinton by 38 points but supported Biden by only 26. There were also more modest signs of eroding support among black and Asian voters. In fact, a key driver of Biden’s win was improvements with white Americans: he lost them to Trump by only 13 points compared to Clinton’s 17-point deficit.

It seems plausible that because Democrats found success in 2020 and unexpectedly did so again in the 2022 midterms, they overlooked real problems under the hood of their coalition. Now, these problems finally caught up with them.

Initial data from the 2024 AP VoteCast survey shows that Kamala Harris matched Biden’s margin with white voters, but Trump made historic gains with non-white voters. He earned the highest share of Asian support since 2004, the highest share of black support since 1976, and the second-highest share of Hispanic support ever (he even nearly won Hispanic men outright). All this points to an American electorate that is becoming less polarized along racial and ethnic lines. While that may be a welcome development for society, it comes at the obvious expense of the Democrats, who had hoped these voting blocs would help them build a demographically dominant coalition for years to come.

Meanwhile, the transformation of the parties along class lines appears to be moving full steam ahead. Harris retained higher levels of support among college-educated voters, winning them by 14 points. But perhaps just as telling: she carried high-income earners (those earning at least $100,000) by seven points—by far the largest margin for a Democratic nominee in the modern era. On the other side, Trump became the first Republican nominee on record to win low-income voters, narrowly carrying them by three points. He also continued growing his advantage with non-college voters, winning them by 13 points—the largest margin for the GOP since at least 1988. And his 44 percent support from union households marked the greatest share for a Republican since Ronald Reagan.

Looking at this picture, it’s hard not to see that the Democrats are becoming the very thing they have long fought against: the party of the elites. This stands in sharp contrast to their longtime image as the champions of the working class, which is further and further in the rearview mirror. According to political scientist Matt Grossmann, college-educated white voters this year became a plurality of the Democratic coalition for the first time ever, surpassing both non-college whites as well as voters of color.

On a more practical note, this new coalition also risks putting the Democrats on electorally unsound footing. Although college graduates are more reliable voters than their non-college peers, they also constitute a much smaller portion of the population. Without a meaningful share of working-class voters in the mix, the party will struggle to be competitive.

Strategists and pundits will argue in the months ahead about the best path forward for the Democrats, but suffice it to say: from both an electoral and moral standpoint, the party’s aim should be to figure out a path to reclaiming its roots as the party of the people.

Editor’s note: A version of this piece first appeared in Persuasion.

Data here, as for all post-2008 elections, is based on collation across a variety of sources—exit polls, the AP VoteCast survey, Catalist’s “What Happened” reports, and Pew Research Center’s voter-validated studies.

As Ruy correctly argues, though, what many people missed at the time was that a key requirement for this new Democratic majority was retaining a sizable share of support—even if not a majority of it—from white non-college voters.

The move of the middle class to the right is really all that matters, and that has been a long time coming. First it was the towns against the gowns, then it became small business v regulators, then religious against secular, then white collar unions v blue collar. And on and on.

The middle class is the productive class, period, and starting with Hillary, the white, working, men were of no interest to her. She was the quintessential liberal, over educated woman, immersed in her own importance. The lower classes were her ladder to even higher levels, and she used them mercilessly. Once that became clear, the liberal elite coalition circled the wagons and more and more Americans realized they were mere tools for this group.

No one likes to be used: men, women, of any color, ethnicity, calling or background. The more insulated the elites became, the whackier their ideology and demands became. They had already declared their superiority, their right to rule and so they thought they could do, say, lie, cheat, act out, any way they liked, and get away with it. They were all experts; get in line peasants. We are coming for the whole world with our globalist, internationalism, which of course, we also run.

People can only be insulted so long, called deplorable, irredeemable, racist, sexist, brainless, useless, garbage, before they collectively sit up, look around, at one another of all stripes, and say, "What, now?" "Say that again?"

This has been coming, on so many levels. So they doubled down, with Biden and Kamala. It seems their heads got so big, they exploded. Finally. Now sanity has a chance and maybe this level of courage requires a little insanity.

Bring it on.

Reading between the lines of Baharaeen's excellent analysis here, it becomes hard to ignore that past Democratic majorities have been built upon, and thus dependent upon, the rapidly disappearing underdog, marginalized, one could even say discontented class of Americans. Prosperity, in that case, poses a threat to Democrats' stranglehold on power. Yes, it's a measure of the dynamic American success story, but also Democrats own fault that they can't seem to grow with that success; that virtually every constituency group of its long-held coalition is now moving toward the Republican Party to safeguard past gains made.

In this respect, it can be said that the Democratic Party has become victim to its own past successes. But in its panic to regain a majority by opening U.S. borders to millions of illegal crossovers in the hooe of gaining a fractured majority, it has only antagonized a majority of Americans and, ironically, accelerated its own faulures.