The Counties to Watch on Election Night

There may be early clues about how the swing states will vote.

Hard as it may be to believe, there is now less than one month to go until Election Day. All signs point to a historically close race, and if the 2020 election was any indication, Election Day could quickly become election week. As the votes are being tallied up, there may be early clues as to how the most competitive states could ultimately break. Let’s take a look at what are likely to be some of the most instructive counties to watch in each state.

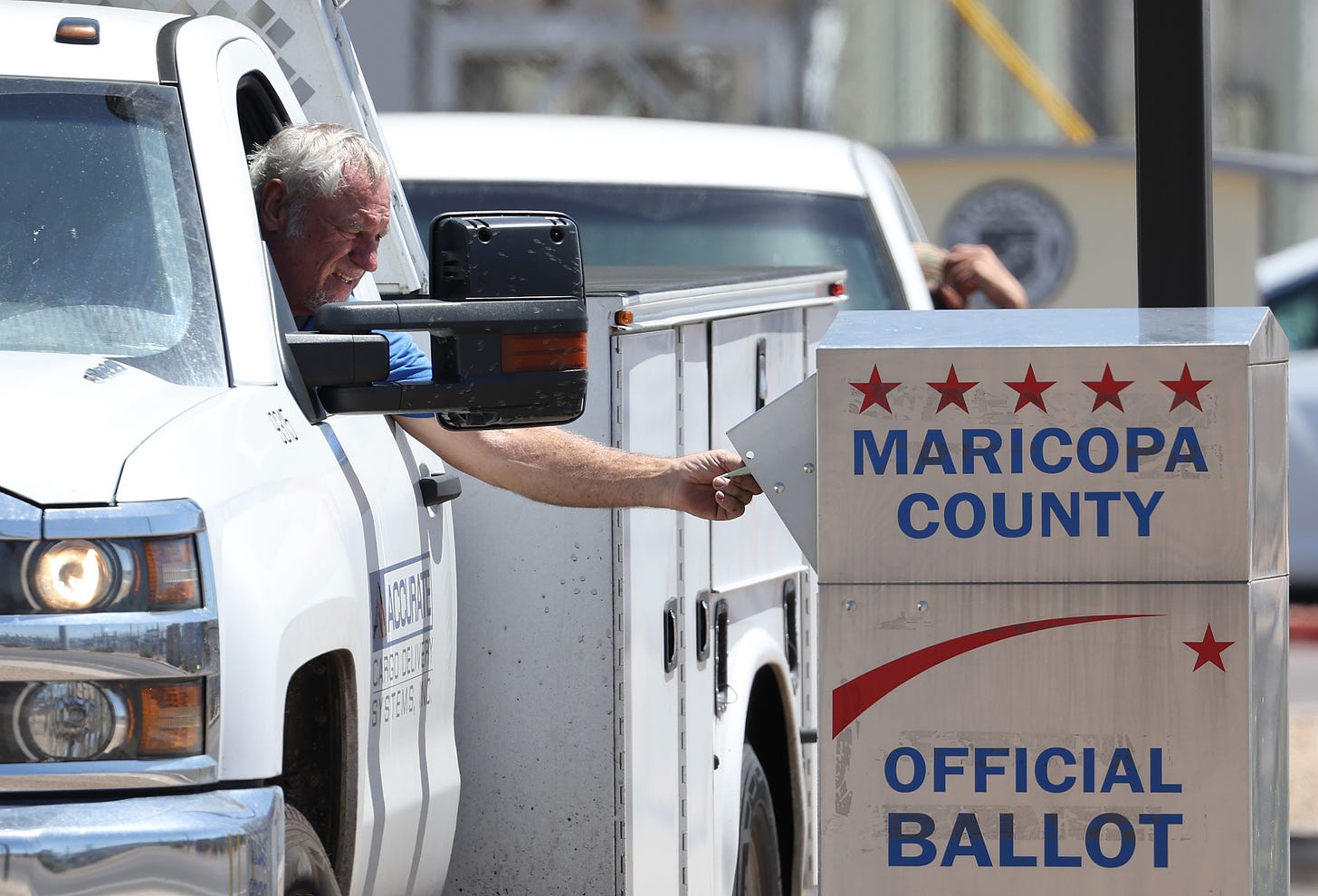

Arizona

The results of statewide elections in Arizona almost always hinge on which candidate wins one county: Maricopa. Home to the sprawling Phoenix metropolitan area, Maricopa accounted for fully 61.1 percent of the 2020 presidential vote, a sign of its outsized influence. Since the state’s creation in 1912, just one presidential nominee has carried Arizona while failing to win its biggest county: Bill Clinton in 1996.

Though Maricopa—and, thus, Arizona on the whole—has long been a Republican stronghold, backing every GOP nominee from 1952 to 2016, it resembles the type of highly educated suburban area that has become more Democratic over the past decade. After voting Republican by double digits in 2008 and 2012, the county only backed Trump by 2.8 points in 2016. Last time around, Democrats finally flipped it, with Biden winning there by 2.2 points and wresting the state from Trump.

All this makes it pretty simple: the candidate this cycle to win Maricopa will be an overwhelming favorite to also win Arizona’s 11 electoral votes.

Georgia

Over the past four decades, Georgia has almost perfectly mirrored Arizona’s voting patterns, backing the GOP presidential nominee in all but one election (1992) during that time. And, like Arizona, as the suburbs around Georgia’s biggest city—Atlanta—have grown more affluent and well-educated, they have subsequently begun voting more Democratic, slowly pushing the state leftward as well.

One county that embodies these trends is Cobb, which covers the northwest Atlanta suburbs including the communities of Marietta and Kennesaw. The third-largest county in the state by 2020 vote share, Cobb was deeply Republican just over two decades ago, backing George W. Bush by more than 20 points in both of his elections. But in 2008, the county swung heavily toward Democrats by more than 15 points, though it remained in the Republican column that cycle and in 2012. In the Trump era, it lurched strongly leftward again, finally flipping to Democrats, with Clinton carrying it by 2.2 points and Biden by 14.3.

Unlike Maricopa, Cobb isn’t large enough to determine the outcome in Georgia by itself. But how the candidates are performing here could be a sign of who has the advantage statewide. If Harris is building on Biden’s 2020 margin, it may reflect growing strength with college-educated suburbanites elsewhere that could position her to win the state. But if she’s merely matching his margin or falling behind, it likely won’t be enough to offset the rightward drift of rural and working-class counties elsewhere.

Michigan

Unlike Arizona and Georgia, Michigan’s electoral map is quite diverse, with candidates needing to win multiple types of places to be successful statewide. With this in mind, there are three counties to keep an eye on for signs of who might have the overall advantage.

The first is Kent, home to the city of Grand Rapids and its immediate suburbs. A fast-growing, well-educated county, Kent has swung substantially leftward over the past two decades, going from backing George W. Bush by 21.2 points to breaking for Biden by 6.1—a shift of 27.3 points. In fact, no Michigan county has become more Democratic during that time. If it continues shifting to the left, Harris may be able to build a bulwark against any possible Trump gains in less friendly parts of the state.

The second is Saginaw. In contrast to Kent, the electorate in Saginaw is very working class: the county’s median household income is roughly $57,000, and only 23 percent of residents have a college degree. Since 2000, it has been the only county to vote the way of the state in every election, making it the ideal bellwether. This means that how Saginaw breaks could be an early sign of which candidate is favored to carry Michigan.

Finally, Wayne is the state’s largest and second-most Democratic county. Given its deep-blue hue, why include it on this list? Because there have been signs of Democratic erosion here. To be very clear: the party continues to win Wayne by overwhelming margins. But Republicans have eaten into their advantage, and there’s reason to suspect that could happen again this cycle. Wayne is home to the city of Dearborn, whose population is majority Arab. Dearborn has become the epicenter of outrage over President Biden’s policies in the Middle East conflict between Israel and Hamas, which could be weakening Harris’s standing in Wayne and jeopardizing her chances of winning the state.

Nevada

The overwhelming share of Nevada’s electorate (70.8 percent in 2020) lives in Clark County, home to the city of Las Vegas. Candidates, usually Democrats, can sometimes win statewide by carrying Clark and no other county given the high concentration of voters here. Democratic Attorney General Aaron ford accomplished this in 2018, for example. However, it’s often not enough.

The state’s true bellwether is Washoe County, which includes the city of Reno and makes up another 18.4 percent of the statewide vote share. Washoe has voted the way of the state in every presidential race this century. Moreover, it is the only county in Nevada that shifted leftward—albeit by a meager 0.8 points—between 2012 and 2020. (The Democrats even lost ground in Clark during that period.)

A sign of its importance: in the 2022 midterms, Nevada held seven contests for statewide offices, and in six of them the candidate who captured Washoe won. In the seventh, the race for governor, incumbent Democrat Steve Sisolak won both Clark and Washoe but still lost his seat to a Republican challenger who fared better in Washoe than some other statewide GOP candidates.

So, although candidates can win solely by taking Clark, success most often favors those who carry Washoe too.

North Carolina

When most people look at election results in the Tar Heel state, they want to know how two counties in particular are performing: Mecklenburg (Charlotte) and Wake (Raleigh), by far the two largest counties in the state. After narrowly voting for Bush, both have since made a steady march to the left. By 2020, they voted for Biden by more than 25 points each.

However, despite their size and growing margins for Democrats, Mecklenberg and Wake have not been enough to tip the state in the party’s favor. So it’s worth keeping an eye on other counties to see whether Team Blue has made up enough ground outside those metro cores to finally get over the hump this cycle. One such county is Cabarrus, which covers the suburbs northeast of Charlotte. Cabarrus typifies the type of county that has moved leftward during the Trump era. It has the fifth-highest median household income in the state and grew at the third-fastest rate during the previous decade. After voting twice for Bush by more than 30 points, it backed the Republican nominee in the next three cycles by 18–20 points. Then, in 2020, it broke for Trump by just 9.4.

If Harris can make further inroads in right-leaning areas like Cabarrus while continuing to build on the Democrats’ advantage in the large urban counties, she may finally help flip the state for her party this year. But if Trump halts her momentum here, it’s hard to see where else she might make up ground.

Pennsylvania

Perhaps no state better represents what my colleague Ruy Teixeira calls the “Great Divide” between major metro areas and smaller rural and exurban communities than Pennsylvania, widely thought to be the most competitive battleground state this cycle. Between 2012 and 2020, the suburbs around Pennsylvania’s two biggest cities, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, shifted to the left while everywhere else moved right. Joe Biden pulled out a win because he both capitalized on his party’s advantage in the metro suburbs and also clawed back losses in other areas.

To see how these trends play out this cycle, there are two counties worth watching. The first is Chester, home to the western Philly suburbs. Like Cobb County in Georgia, Chester is the archetype of today’s blue-trending counties. It is tied for the fourth-highest population growth in the state over the past decade; its population is heavily white (84.9 percent), highly educated (51.2 percent hold a bachelor’s degree), and very wealthy (the median household income is $110,000); and voters here turn out at the second-highest rate (73.4 percent) in the state.

After narrowly backing Romney by 0.2 points in 2012, Chester swung to the left and backed Clinton by 9.5 points. Four years later, it nearly doubled, voting for Biden by 17.1. If Chester and other suburban counties continue trending Democratic, it will put pressure on Trump to win back ground he lost to Biden in other parts of the state—a definite possibility, but not a given.

In the opposite corner of the state is Erie County. Situated along the eponymous Great Lake, Erie is everything that Chester is not. The county experienced a population loss of 3.5 percent during the previous decade, and residents here are far likelier to be working class: its bachelor-degree attainment rate is just 26.6 percent, and the median income is $56,000, well below the statewide average. Despite the county’s unfavorable demographics for Democrats, it has backed the party by wide margins in recent elections, including Obama by 16 points in 2012, thanks in part to a strong union tradition in the region. However, Erie swung sharply to the right four years later, backing Trump by 1.6 points. Biden flipped the county back in 2020, though barely, winning it by a just one point.

It’s very possible that as Erie goes, so goes Pennsylvania—and the election. But if Harris can amass even bigger margins in the vote-rich Philly suburbs, she may be able to withstand minor losses in other parts of the state like this (though betting on that is a risky proposition).

Wisconsin

The Badger State’s political terrain shares many similarities with that of its Midwest peers, including the fact that the state’s two largest counties—Dane (Madison) and Milwaukee—tend to attract outsized attention on election night, even though they aren’t powerful enough to sway elections on their own. Winning Wisconsin requires organizing a more diverse path to victory.

There are two other counties whose results may be more instructive of which candidate has the edge in the state. The first is Waukesha, which encompasses the suburbs directly west of Milwaukee. Like the other counties abutting Milwaukee, Waukesha is very conservative—it has voted Republican in every presidential election since 1968, usually by double digits. However, over the past decade, this support has softened, likely due in no small part to its demographics: it has the third-highest college attainment rate in the state (43.9 percent) and a median household income of $102,000. Since 2012, Waukesha has moved nearly 14 points to the left. If areas like it, which tend to have high voter turnout, continue drifting leftward, it could spell trouble for Trump as he works to flip the state back.

Then there is Sauk County, a popular summer vacation spot located in the southwest region of the state. In contrast with Waukesha, Sauk is more working class, with a bachelor-degree rate of just 25.2 percent, though its median income of $73,000 is on par with the statewide average. It is the only county in Wisconsin to back the same candidate as the rest of the state in every election since 1992. Mirroring Erie in Pennsylvania, Sauk supported Obama by double-digit margins before turning around and narrowly voting for Trump (by 0.3 points) in 2016. Biden bounced back in 2020, capturing it by a larger 1.7 points, but this remained far below Obama’s performance.

There are other counties around the state whose demographics are similar to those of Sauk, which could be prime territory for Trump to make gains. However, if Harris offsets that in places like Waukesha, she may be able to hold the line and keep the state in the Democrats’ column at least one more time.

I don't know about some of the others---pollster Richard Baris says the WI shift is staggering and so does my DecisionUSA2024 election night statistician, Seth Keshel---but I can tell you Arizona will be completely gone to Democrats. Period. Full Stop. Maricopa yesterday added over 600 R registrations in 8 hours for staggering 172,000 LEAD just in this county. No, Ds won't come close. Maricopa will be R+3-4 on election day & will have close to 1 MILLION registered Rs. The state as a whole now is looking R+7. I can also speak to internals I've seen of Clark, which is now R+2. I know, shocking. But the rightward shift in NV is heavily driven by anti woke Hispanics. We have recent EARLY VOTING data out of VA and it's not good for Ds either, with a net shift since 2020 of over 20 points and the overall early vote way down.. Pennsylvania is also getting into the "lock" zone for Trump. Virtually all polls show him up 2, meaning he's up over 4 because of the underpoll. PA Ds are down 400,000 from their 2020 number in registrations. And the last NC poll was Trump +4, right where I have him. Elissa Slotkin last week said Ds were "underwater" in MI, so I wouldn't count on Wayne, particularly since a coalition of Arab groups came out against Harris. Right now I have the election as Trump +1 to 2 nationally and 312 EVs, but a tier of states I did not put in the mix, ME, VA, MN, NM, and NH, are now totally in play (last NM poll was Trump down by only 4). The senate races are now R+3 pickups (WV, MT, OH) with MI and PA even and last week Baldwin's crew said they were in trouble in WI, only up 2 (again, the Trump underpoll means this very likely is another loss. Same with Slotkin). Gonna be a very long night for Democrats.

But given the rapidly growing crime and dysfunction of urban America, compounded by Democrats' open borders' culpability, it may prove a stretch to assume, based on past performance, that the party has a lock on these traditional Democratic strongholds. And then there's the not-so-little matter of the Harris/Walz glaring weaknesses that fail to inspire confidence.