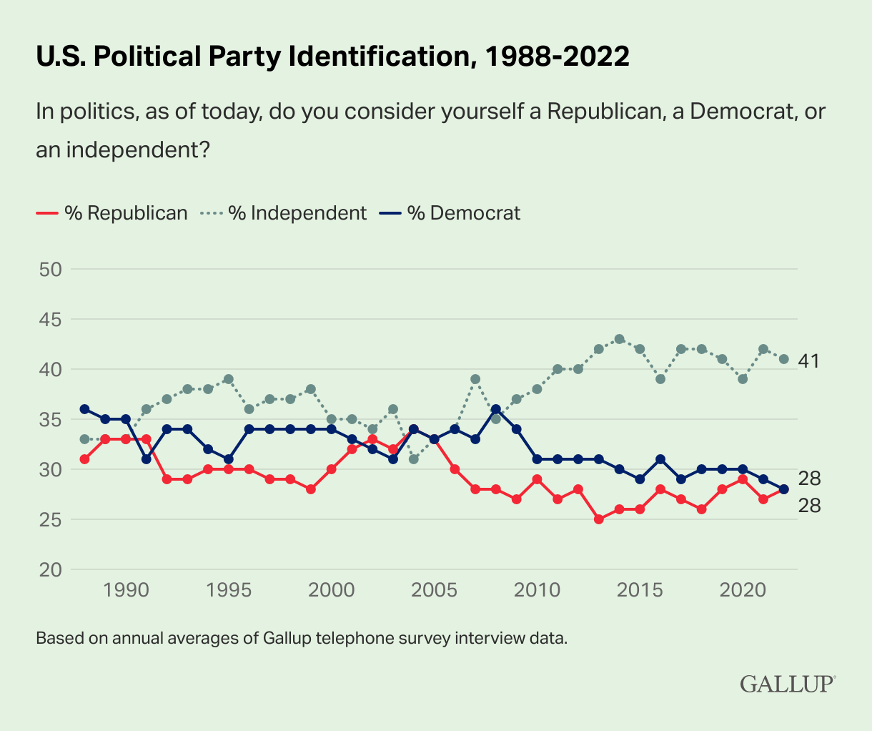

Gallup is out with new time series data showing that the percentage of self-identified independents remains at a historically high level with 41 percent of Americans calling themselves independent in 2022—far above the less than 3 in 10 Americans, respectively, who identify as either a Democrat or a Republican.

Forced to choose, independents still break equally between the two parties thus producing a near even split in party identification in the United States: 45 percent Republican/Lean Republican and 44 percent Democrat/Lean Democrat.

As TLP has argued before, political scientists and party strategists too readily write off independents as closet partisans when in fact these Americas are a diverse group worthy of much more serious consideration. Pretending that independent voters will always get with the program by hating one side more than the other—or by grudgingly accepting the party line established by a small pool of party elites and diehards—is a recipe for unpopular parties and bad politics. This flippant attitude towards independents goes a long way in explaining why the party brands of both Democrats and Republicans are so dismal in the eyes of many voters, and why the two parties in Congress receive such poor favorability numbers.

Democrats and Republicans tend to treat independent Americans like a bunch of schlubs who can be bossed around by party loyalists and forced to toe a line that is not of their choosing every election. But if the parties approached independents with more respect and curiosity, they might learn something important about how citizens process complex public policy issues and then shape their party platforms and priorities accordingly.

For such a large group of voters, little is concretely known about independents in terms of their precise make-up, views, basic values, and sometimes quirky and ideologically malleable policy preferences. Based on available studies, one thing seems clear though: Independents do not constitute a uniform or coherent bloc of voters. The concept that a single independent party could represent this 40 percent chunk of voters—even if such a party were viable in electoral terms—seems off the mark.

From what I can tell from existing research, awaiting a deeper dive and more data, there are essentially 4 categories or types of independent voters:

“We need more moderates”

Populist-left

Populist-right

Deeply disaffected and disengaged

We’ll explore each of these groups in a series of posts starting with the largest group: the “We need more moderates”.

More in Common is a splendid organization that has spent as much time as anyone looking into the composition, views, and beliefs of what they label “the exhausted majority” of Americans, many of whom are political independents (although not all). More in Common argues that these exhausted voters are fed-up with partisan polarization in politics, feel overlooked and under-appreciated, hold flexible views not easily captured by the two parties, and want more common ground in politics.

This seems like a reasonable formulation of the basic worldview of the largest cohort of independent voters.

A recent study by More in Common and YouGov, conducted just before the 2022 midterms, provides fascinating information specifically on independent voters which they classify using both self-reported party registration and self-reported party identification among all adult citizens.

Among the 2000 U.S. adults surveyed, roughly three-quarters report being registered as either a Democrat or a Republican, and about one quarter report not being registered as a member of either party. As seen below, 60 percent of these unaligned Americans (but not necessarily registered independents) report that the main reason they are not a member of either party is that “neither party’s ideals align with mine” with around 3 in 10 citing other reasons and 12 percent saying their “vote doesn’t matter anyway”.

Unlike those registered Americans who feel close to their party's values, the bulk of Americans who are not aligned with either party obviously feel alienated from the values of both Democrats and Republicans. But this idea could indicate a whole range of attitudes: for example, it could indicate a belief that the parties are not anti-establishment enough or perhaps too timid and pro-corporate for their tastes, or conversely, it could mean that the two parties aren’t sensible and moderate enough for them.

Fortunately, in follow-up questions, More in Common/YouGov honed in on this issue a bit more, asking Americans whether they think the Democratic and Republican parties, respectively, need more moderate candidates.

As seen in the table below, roughly half the country overall (49 percent) believes that Democrats need more moderate candidates with a similar proportion of Americans (47 percent) also believing that Republicans need more moderate candidates. Notably, two-thirds of both self-identified Democrats and self-identified Republicans say that the other party needs more moderate candidates, but less than 4 in 10 Democrats and 3 in 10 Republicans believe that their own party needs more moderates.

"Moderate candidates for thee but not for me" is the prevailing partisan attitude.

Independents, on the other hand, mostly believe that both Democrats and Republicans need more moderates: 54 percent of independents feel that Democrats need more moderate candidates while 49 percent of independents feel the same way about Republicans. The remaining half of independents split roughly between those who believe that the parties do not need more moderate candidates and those who don’t know.

Combined, these findings suggest that the largest percentage of independent voters—around half—desires more moderation in American politics, understanding that the term “moderate” itself probably connotes different things to different people.

It’s safe to say that the “We need more moderates” group of independents doesn’t particularly like the ideological hotheads and culture war blowhards on either the right or the left who pop up all too often in contemporary politics, mostly through closed partisan primaries or elections in non-competitive congressional districts and states.

Instead of putting up more of these extreme candidates for office—and allowing them to be the face of the parties—Democrats and Republicans might want to figure out what exactly constitutes an ideal moderate candidate in the eyes of independent voters and take steps to more effectively reach these voters and win their support.

(Next week’s post will examine the populist-left and populist-right independents.)