Targeting Distressed Places

Why it matters, why it’s hard, and how it can be done.

As I’ve argued in several columns over the past few months, policies to bring job opportunities to distressed places—neighborhoods or local labor markets with low employment rates—can help these places, their residents, and the nation. Different types of places have different needs, but evidence shows that place-based policies can help spread employment opportunities to all Americans.

But why should we target distressed places? That is, why should the federal or state government provide more resources per capita to help distressed places, as opposed to average neighborhoods or local labor markets? After all, residents in average places would also benefit from expanded access to good jobs.

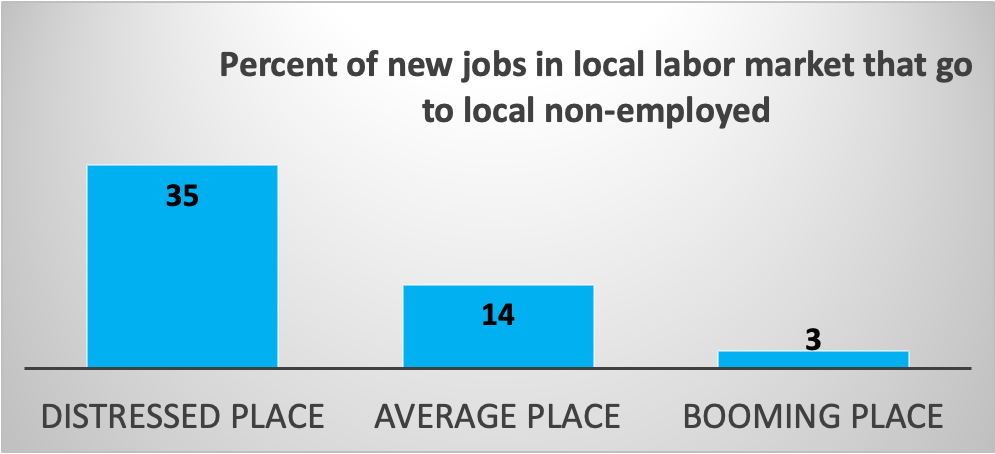

Targeting has two good rationales. First, distressed places benefit more from place-based policies. In distressed places, for instance, the effects of job creation on local employment rates—employment to population ratios—are higher. When we create jobs in an already booming area, very few of those jobs—around three percent—end up going to local people without jobs. The remaining 97 percent end up leading to in-migration.

Why do only three percent of new jobs go to local residents in a booming place? Our focus should be on the ultimate effects of new jobs, not the immediate effects. Local new jobs are filled by three types of hires: (1) local employed residents, (2) local non-employed residents, and (3) in-migrants. When jobs are filled by the local employed, this creates a job vacancy, and this job vacancy is filled in the same three ways. At the end of these job vacancy chains, a new job either leads to a new job for a non-employed local resident or an in-migrant—someone who moves to town to fill a job vacancy created along this vacancy chain.

Along these job vacancy chains, employers make choices about who to hire. If more local residents are non-employed, more of these hires will be the local non-employed. If few local residents are non-employed, more hires will be in-migrants.

The second rationale for federal or state government targeting of distressed places is the inadequacy of tax bases in distressed places. Almost by definition, a distressed place with higher non-employment and lower per capita earnings will have a lower per capita tax base. Place-based policies are costly compared to these tax bases.

For example, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)—arguably the most successful federal regional economic development program of all time—at its peak had annual per capita spending in the region of about $300 in today’s dollars. Suppose some local government in the United States wanted to do a local economic development strategy of similar intensity to TVA. That level of spending—$300 per capita—would be about 14 percent of average local tax revenue. Distressed places would find it extraordinarily challenging to allocate 14 percent of their tax revenue for long-term economic development purposes.

There’s a strong rationale for targeting distressed places, but both the federal government and state governments find such targeting difficult. One reason is obvious: if this targeting means that place-based policies aid only a few places, only a limited number of voters will benefit—meaning it will prove politically challenging to get majority support.

A second reason for targeting’s difficulty is the way many economic development programs are tied to specific projects. Programs tend to focus on aiding specific location or expansion decisions, particularly large branch plants or headquarters of major corporations. The number of such projects is much higher in non-distressed places versus distressed places—that’s one reason that distressed places are distressed in the first place! If most economic development program dollars are tied to specific location or expansion decisions, there’s some tendency for dollars per capita to be higher in non-distressed places as a result.

A third reason for difficulty is that it’s difficult to tie aid to a place’s distress if this aid is not itself tied to helping people. The argument that a job in a distressed place has a higher value than a job in a non-distressed place is ultimately justified by the different benefits for people, but the argument is complex, indirect, and hard to grasp intuitively.

Because it’s hard to target distressed places, targeting is rare and difficult to sustain long-term. In the 10 most populous states, for example, the share of economic development resources that go to programs with any targeting averages 11 percent. Even in programs that are targeted, the eligibility criteria area broad enough that less than one half of these programs’ resources go to distressed places.

Moreover, targeted programs frequently start out small but then expand to become non-targeted. For example, New York’s now-defunct “Empire Zone” program began in 1986 as an enterprise zone program, with tax breaks for investments and job creation limited to only ten highly distressed areas. In 2000, the program was still highly targeted and small, at an annual cost of $30 million. But in 2001 the program was expanded statewide, and incentive payments to firms made more generous. Costs escalated to almost $600 million annually by 2008 before new program commitments were terminated in 2010.

Even successful and sustained targeting programs have difficulty keeping the dollars in distressed places with project-based funding. From 1998 to 2014, for example, North Carolina’s economic development programs aimed at being highly targeted by county distress. In the 2007-2013 period, firms creating jobs in distressed counties were eligible for job creation credits of $12,500 per job, those in medium-distressed counties could receive credits of $5,000 per job, and jobs in the least-distressed counties only received $750 per job. Despite these large differentials, in 2015, North Carolina’s economic development resources were distributed as follows: $13 per capita in annual aid to the 40 most-distressed counties, $19 per capita to the 40 “middle-tier” counties, $1 per capita to the 20 least-distressed counties. Targeting proved successful in helping the state’s bottom 80 counties—but not in directing the most aid toward the bottom 40 counties.

What can be done to make targeting distressed places more widespread and sustainable?

First, economic development aid can be distributed via a block grant that is higher per capita in distressed places, as I have proposed in several past articles. Such a block grant system makes sure that more economic development aid does not automatically flow to a place if it simply has more locations or expansion projects.

Economic development block grants have another advantage: they allow local strategies to be adapted to the distressed place in question. Whether the area’s overriding need is trained workers, infrastructure, industrial sites, or child care, a block grant can have broad enough permitted uses to help communities to address their local needs.

Second, economic development block grant formulas can be developed that are higher per capita for distressed places but that provide at least some aid for a majority of places and thereby enhance the likelihood of broad-based political support.

Third, block grant aid formulas can be clearly related to the number of people in a place who need employment aid. As I have proposed, grants could be equal to some dollar amount multiplied by the number of local residents needing jobs in a particular place.

Here’s how the federal government or a state government might do such calculations for a block grant program: the state or federal government would define a local ratio of employment to population that’s a full employment target, calculate the difference between this target and the number of people actually employed at present, and multiply some dollar amount by the resulting figure. Differences in place funding per capita would then be due to different numbers of people needing jobs, not some form of discrimination for or against particular places.

This funding approach—tying disparate per capita place funding to different numbers of people needing help—is similar to how states have often been able to successfully target school aid. Many states have formulas in which all students receive some state aid per student, for instance, but students eligible for free or reduced price lunch (below 185 percent of the poverty line) receive significantly more state aid. The resulting state school aid is “place-targeted”—some school districts get more per student—but this is due to diverse student needs, not arbitrarily favoring one school district over another.

It's justified to target distressed places because more people in these places need greater job opportunities. If we design targeting formulas that recognize these greater needs while also recognizing the real but lesser needs of people in more average places, federal and state targeting of distressed places may well be more sustainable at a larger scale.

Timothy J. Bartik is a senior economist at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, a non-profit and non-partisan research organization in Kalamazoo, Michigan. His research focuses on state and local economic development policies and local labor markets. At the Upjohn Institute, Dr. Bartik co-directs the Institute’s research initiative on place-base policies.