Still no demand for “restraint”

What a new poll on foreign policy attitudes reveals about public opinion

In the wake of the American retreat from Afghanistan, foreign policy and political commentators claimed that President Biden’s decision to pull U.S. troops from the country reflected a widespread public desire to reduce America’s military commitments overseas. Those who supported the withdrawal applauded this perceived shift in public sentiment, while those who opposed it deplored the public’s apparent readiness to shirk American global responsibilities.

But as a new poll on public attitudes toward foreign policy commissioned by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs shows, the American public has little appetite for what proponents of wholesale U.S. military retrenchment call “restraint.” While a previously ambivalent American public supported President Biden’s decision to pull out of Afghanistan after it had been made, that support hasn’t translated into backing for the wider program of neo-isolationism that sails under the “restraint” flag. It’s something the Biden administration would do well to recognize even as it leans on many “restraint” advocates to defend its Afghanistan policy.

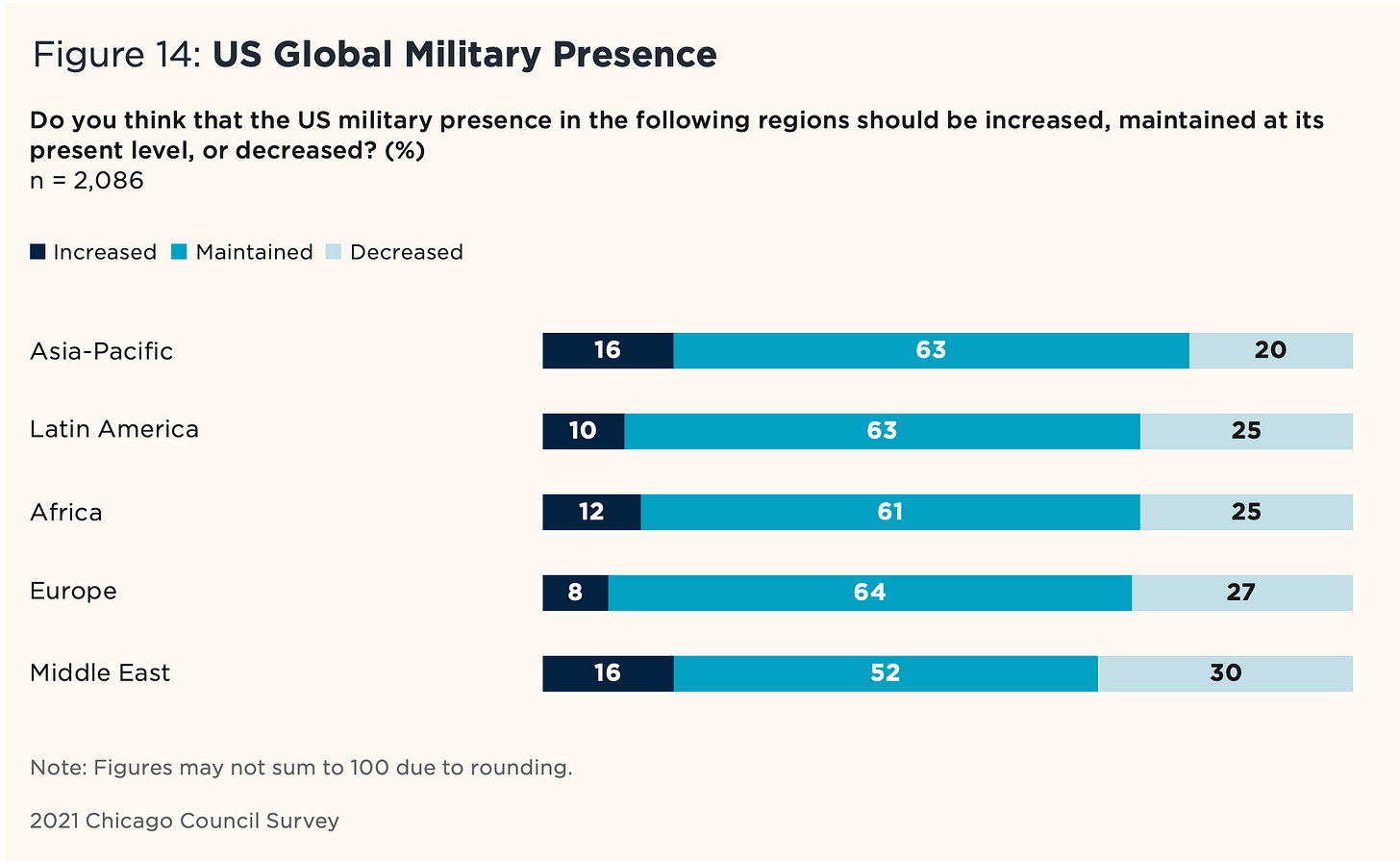

Indeed, the poll – the latest in a long-running series published by the Chicago Council – shows that majorities of Americans reject the idea that the United States should pull back from the world militarily. More than two-thirds of Americans think the United States should maintain or increase its military presence in every region surveyed: the Asia-Pacific, Latin America, Africa, Europe, and even the Middle East where some 68 percent of the public wants to increase or keep the U.S. military presence there the same.

In contrast to one of the core tenets of the “restraint” faith, moreover, the public sees defense agreements and U.S. military bases overseas as a useful foreign policy tool that the country either uses not enough (28 percent) or the right amount (42 percent). Further, over two-thirds of the American people think the United States employs armed force “such as drone strikes and military interventions” the right amount (40 percent) or not enough (28 percent). The public certainly prefers non-military tools like humanitarian aid (85 percent not enough or right amount), diplomatic tools like alliances and international agreements (83 percent), and economic measures like sanctions (82 percent) to military ones, but it’s clear that most Americans don’t see diplomacy, aid, or sanctions as at odds with overseas military bases or the use of force.

What’s more, Americans are now more willing to defend the country’s overseas allies and partners than before. All the scenarios presented by the Chicago Council’s pollsters – defending South Korea against a North Korean attack, defending NATO allies in the Baltic against a Russian invasion, protecting Israel against an attack by its neighbors, and using U.S. troops to defend Taiwan against China – command majority support. That’s a marked contrast with just seven years ago, when none of the four hypothetical situations offered received majority backing from the public.

Nor are Americans necessarily on board with reductions to the defense budget or the overall size of the U.S. military. Only 15 percent of those polled said they wanted to decrease the military’s size, while a majority (52 percent) said it should remain the same. When asked to divvy up the U.S. federal budget, moreover, on average those surveyed said they’d dedicate $15.69 of every $100 in public spending to the defense budget ($11.90) and military aid to other nations ($3.79). That’s not that far off from what the share of its budget the United States actually spends on defense – some 16.8 percent of all federal spending in 2015 (percentages from 2020 are skewed by massive COVID-19 relief spending).

These responses probably reflect a bias toward the status quo, at least to some degree. But that’s precisely the point: Americans are largely comfortable with their country’s military presence around the world and, contrary to the arguments of “restraint” advocates, see no upside in reducing it. They may want the United States to use diplomatic, humanitarian, and economic tools more often than it does now, but that doesn’t mean they think the country’s overseas military bases are a burden or that it uses force overseas too much. It’s not surprising to see that most Americans find the current size of the defense budget perfectly acceptable. At the same time, the poll’s time series data indicates that Americans have become more willing to defend allies overseas against attack from hostile powers.

There’s plenty more interesting data to be mined from the Chicago Council’s poll, from generally positive attitudes toward trade and globalization to widespread support for public investment in cutting-edge technologies to a deep skepticism of the U.S. relationship with China. Overall, however, the bottom line is clear: few Americans seek the sort of sweeping military pullback from the world on offer from the “restraint” school. On the contrary, Americans by and large remain internationalist in outlook and instinct.

That doesn’t mean there won’t be disagreements, often severe, on the specifics of U.S. foreign policy – especially on the question of military intervention overseas. But public backing for withdrawal from a conflict like Afghanistan doesn’t necessarily equal support for wider military retrenchment. Nor does the public see diplomacy, foreign aid, and military force as mutually exclusive, or that involvement overseas logically comes at the expense of investment at home as is so often assumed.

It’s something the Biden administration and all of us involved or interested in foreign policy should remember moving forward. Calls to “come home, America” won’t resonate with the American public as much as retrenchment advocates might think. Most Americans support staying engaged in the world – but want a clearer notion of how their country’s foreign policy syncs up with its plans to invest more at home.