Save America's Robotic Explorers!

How stingy budgets and snafus threaten American leadership in robotic space exploration

Last Thursday marked fifty-four years since Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first human to set foot on another world.

But it wasn’t an entirely happy anniversary for NASA: Congressional committees released their first drafts of the agency’s annual budget a week earlier, and the picture they painted for American space exploration was dim. Both House and Senate versions provided NASA with less than the $25.38 billion than it received last year, and much less than the $27.18 billion the Biden administration had requested. Taking recent inflation into account, that’s effectively a cut to NASA’s budget at the same time the agency aims to return astronauts to the Moon and embark on a series of new robotic exploration missions.

It's a cut that was probably in the cards the moment Congress passed the Fiscal Responsibility Act last June, which raised the debt ceiling and put a cap on federal spending for the next two years. After President Biden signed this bill into law, NASA Deputy Administrator Pam Melroy conceded it was unlikely the agency would receive its full funding request. Still, it’s hard to say that an additional two billion dollars for NASA would have broken the bank here—or even that it would have deprived other, equally worthy government endeavors of funding.

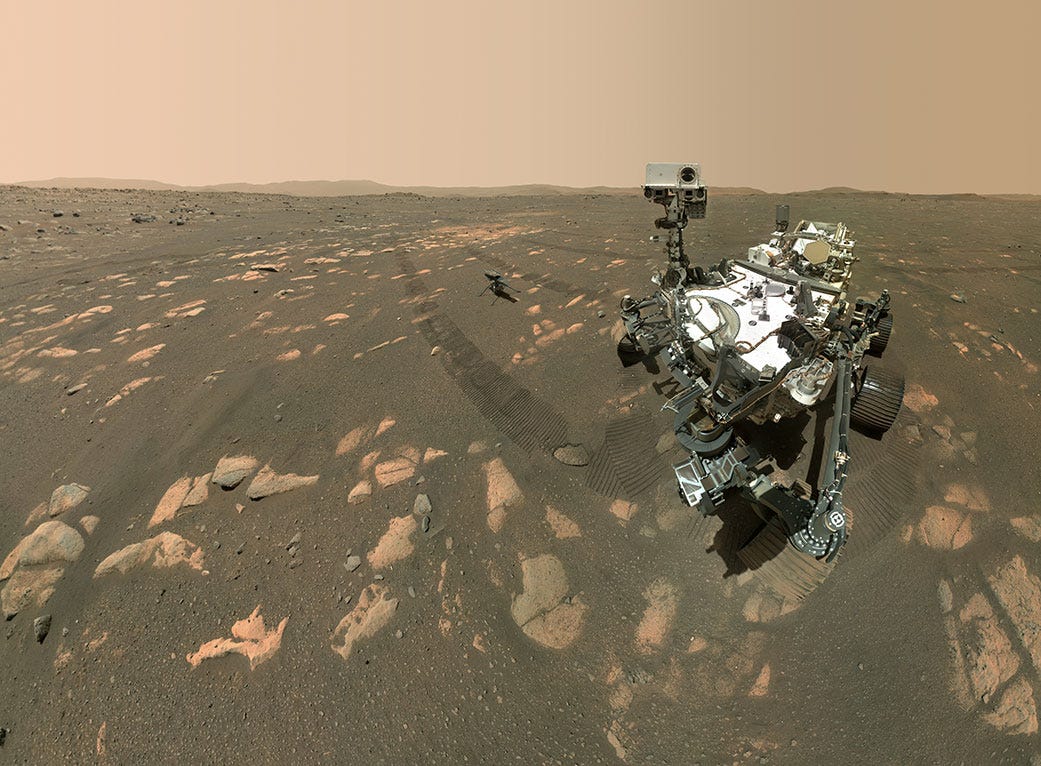

Indeed, Congressional appropriators singled out one particular NASA program for the budgetary axe: the Mars Sample Return (MSR) mission, a cooperative venture with the European Space Agency (ESA) intended to bring Martian soil samples currently being collected by the Perseverance rover back to Earth for in-depth study. NASA itself recently came up with an admittedly “highly speculative” estimate that the mission could cost $8 to 9 billion in total, or more than twice an earlier 2020 estimate. The Senate committee minced no words, slashing requested funding for the MSR mission by over two-thirds and demanding NASA provide a year-by-year plan to keep it within its previously projected budget—or “face mission cancellation.” It’s fair to consider this language something of a suspended death sentence for the MSR mission, a temporary reprieve to see if NASA can come up with a realistic funding plan that Congress can live with in the years ahead.

It’s not the first time something like this has happened for a major NASA robotic mission: the James Webb Space Telescope that’s now beaming back stunning images of the cosmos once faced a similar threat back in 2011 as it went over-budget and suffered substantial delays. A Congressional compromise saved Webb, and it’s likely that something similar will happen with MSR. Congress is right to express concern over MSR’s cost and schedule problems, just as it was right to keep close watch over Webb as its development proceeded.

Still, America needs to make MSR work—returning bits of Martian soil back Earth may be hard and expensive, but more importantly it’s an impressive and scientifically valuable feat of science, technology, and ingenuity, one Americans can take justified pride in if and when it happens. What’s more, it implicates America’s relationships with our European allies: ESA will build the orbiter that will return these pieces of Mars to our own planet. Not for nothing is NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory making the case for MSR via its social media feeds. As with Webb, the threat of Congressional cancellation may be the shock to the system needed to keep MSR close to schedule and budget—but it’s an extreme tactic rather than a viable policy for America’s robotic exploration enterprise.

But the budgetary problems confronting this enterprise are much broader than one major program with funding issues. Earlier this year, for instance, the head of NASA’s Planetary Science Division—the agency’s main robotic exploration arm—warned that her organization’s budget was “a bit brittle and fragile” and faced “significant stress.” Some of that has to do with COVID-related disruptions to supply chains and work environments, and some of it has to do with economy-wide inflation imposing higher costs. Delays to the Psyche mission to study a metallic asteroid scrambled NASA’s robotic exploration plans even further, stretching its resources even thinner—thanks to the Psyche’s delayed launch, for instance, NASA pushed the launch of the VERITAS mission to Venus back to 2031 at the earliest and nearly zeroed out funding for it in the agency’s most recent budget request.

Whatever its ultimate causes, this budget crunch threatens to starve America’s robotic exploration program, leaving it to slowly wither over time as missions get delayed, canceled, or even forgone altogether—even if Congress transfers funding from one defunct program to another, more promising one. These robotic explorers have been an incalculable national asset for the United States, ones that have not only expanded the frontiers of human knowledge but put American know-how and ambition on display for the whole world to see. NASA’s robotic exploration program needs to be protected and nurtured, not left to slowly bleed out due to inadequate funding.

It's also imperative given the new space race that’s emerged over the past decade or so, as newer entrants like China, India, and the United Arab Emirates seek to demonstrate their own national technological prowess and ambition by sending robotic missions to the Moon, Mars, and the asteroid belt. Similarly, geopolitics here on Earth make cooperation between the United States and its long-time allies in Europe and the Pacific even more necessary; due to Russia’s war against Ukraine, for instance, ESA removed its ExoMars rover from a Russian rocket and teamed up with NASA instead. Japan likewise has plans to send a robotic explorer to the Martian moons later this decade, a mission that will see significant contributions from NASA, ESA, and the French and German national space agencies.

Unfortunately, NASA’s budgetary situation isn’t likely to improve any time soon; the federal government still has to live with another year of spending caps thanks to the debt ceiling deal. Once these caps lift, however, funding for robotic exploration needs to rise if America is to meet the ambitions we’ve already set for ourselves. Something on the order of an additional $1 billion a year—a drop in the bucket of a multitrillion-dollar federal budget—would probably do the trick. In inflation-adjusted terms, that would only take NASA’s overall funding back to where it was in the mid-1990s—albeit as a noticeably lower share of overall federal spending.

It’s certainly true that NASA’s robotic exploration program has its fair share of problems, from the MSR cost overruns to the Psyche launch delays. Nor can every problem be solved with more money, of course. But additional funding can help solve some problems—or at least make sure problems in one area don’t delay progress in another.

America’s robotic exploration program remains one of our comparative advantages, a matter of national prestige and standing as well as a point of scientific and technological collaboration with our allies and partners overseas. We’d do well to take care of it and make sure America remains the world’s undisputed leader in space exploration over the years and decades to come.