Across the battleground states, down-ballot Democrats are running well ahead of President Biden. This delta has been a defining electoral feature since the 2022 midterms, where congressional Democrats significantly outperformed expectations set by Biden’s poor approval rating. With the incumbent back on the ballot in 6 months, some Democratic strategists hypothesize that down-ballot strength will lift Biden to victory. In essence, a reverse of the traditional coattails effect.

Two of the most commonly cited examples are in North Carolina, where the disastrous Mark Robinson won the GOP gubernatorial nomination, and in Florida, where an abortion rights amendment qualified for the 2024 ballot. Could either carry Biden to a statewide victory? Unlikely.

North Carolina has an extensive history of ticket-splitting in presidential years. In 2016, Democrat Roy Cooper narrowly won the governor’s race despite Hillary Clinton losing by 3.6 points. Four years later, Cooper won reelection by 4.5 points, even as Trump yet again carried the state.

Mark Robinson, who has a well-documented history of sexist and anti-Semitic comments, is undoubtedly a worse nominee than Pat McCrory or Dan Forest. Josh Stein, this year’s Democratic nominee, might well eclipse Cooper’s 2020 margin. But this does not mean Biden will win the Tarheel State. A recent Quinnipiac poll has Stein up 8 points, but Biden down 2. Notably, Stein pulls a chunk of traditionally conservative voters, but Biden receives no such bump.

Political science research supports this state-level polling. In an analysis of five decades of presidential elections, Yale’s David Broockman finds that “Democratic presidential candidates do not appear to receive any spillover benefits” from down-ballot candidate overperformance.

Furthermore, down-ballot advertising—like the deluge that will hit Robinson over the next six months—is not likely to boost the top of the Democratic ticket. A 2021 paper from John Sides, Lynn Vavreck, and Chris Warshaw shows that “advertising is not consistently associated with the relative turnout of Democrats and Republicans” and “ads for one race do not substantially ‘spill over’ and affect outcomes at another level of office.” North Carolinians may dislike Mark Robinson, but this won’t translate to a better performance for Biden. Recall in 2020, for example, that Susan Collins and Chris Sununu didn’t save Trump in Maine or New Hampshire. Democrats would be foolish to rely on such an effect in North Carolina.

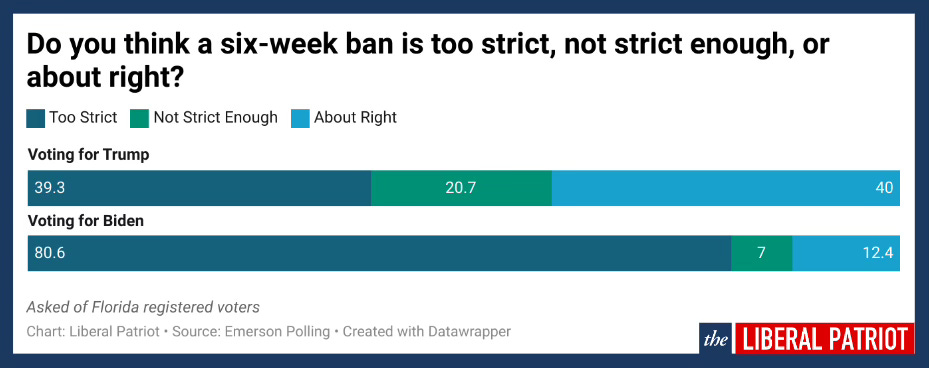

Similar logic applies to the abortion ballot initiative in Florida. The six-week ban set to take effect on May 1 is unpopular across the political spectrum. According to recent polling, 40 percent of Trump supporters say the ban is too strict. The Biden campaign hopes to capitalize on this discontent by linking the reelect to the pro-choice side.

But, as with a down-ballot candidate, the initiative is unlikely to significantly help Biden in the Sunshine State. Should the Biden campaign nationalize the amendment, a traditional coattails effect is more likely, which would actually harm the pro-choice effort. If Floridians view the amendment as synonymous with Trump vs. Biden, its many GOP supporters could be polarized against the initiative—rather than against Trump—and subsequently hold the pro-choice side below the requisite 60 percent.

Some might argue that Arizona is clear evidence for a reverse coattails phenomenon. In the wake of this month’s state Supreme Court ruling, Arizona Republicans are scrambling to distance themselves from the draconian 1864 law. Meanwhile, an abortion initiative is set to appear on the 2024 ballot. Biden will campaign against the ruling, as will Ruben Gallego, and abortion access remains a decidedly winning issue for Democrats. While a Biden victory in Arizona might owe partially to smart pro-choice politics, the ballot initiative itself won’t be what drives a Democratic victory.

The “reverse coattails” theory is appealing for Democrats worried about the neck-and-neck presidential race. But down-ballot Democratic strength (or GOP weakness) does not guarantee wins at the presidential level. Biden will have to win reelection on the strength of his own campaign.