Editor’s note: This is the third release in a new TLP series surveying major domestic and foreign policy issues facing the country. These articles will explore the basic factual context shaping each policy area, examine the major positions on offer across the ideological spectrum, and evaluate which ideas are best—or if new ideas may be needed—to help advance a common-sense perspective in American politics and policymaking.

A Short History of American Energy Policy

The United States has always been a global energy superpower. Most major modern energy production and consumption technologies were invented and commercialized with some involvement from the Department of Defense, NASA, and U.S. National Laboratories.1 Since the oil crises of the 1970s, American energy policy was reoriented towards an emphasis on alternative energy production, both for unconventional fossil fuel resources and low-carbon energy including renewable electricity technologies like solar and wind as well as commodity crop biofuels.

This policy has paid out over the last 15 years with the shale fracking revolution, the explosive growth of solar photovoltaics and onshore wind energy, the growing popularity of hybrid and fully electric vehicles, and promising early-stage innovation in advanced nuclear reactors, deep-earth geothermal energy, hydrogen electrolyzers, and more. These technological revolutions were a long time coming.

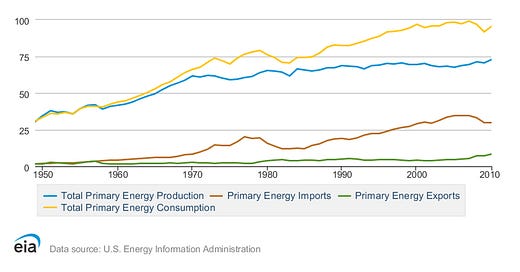

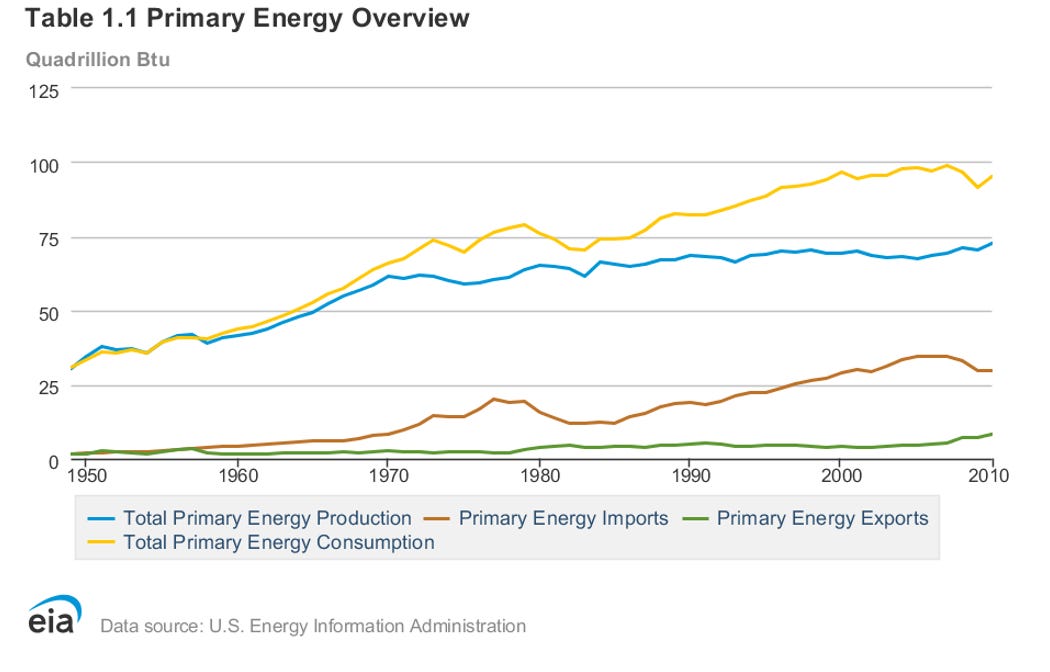

From the 1980s through the early years of the 21st century, both domestic consumption and production of energy plateaued. Policies like energy efficiency mandates, the corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards for automobiles, and the gradual economic shift from manufacturing to knowledge and services combined to stabilize energy production, and then consumption, growth across sectors of the American economy.2

Over this period, the composition of US energy supply remained largely stable.3

Gasoline and other refined petroleum products remained the almost exclusive fuel of the transportation system. A reasonably stable mixture of coal, natural gas, nuclear energy, and hydrological dams continued to generate the bulk of US electricity. Residences and buildings relied on diverse fuel sources—electricity, natural gas, heating oil—depending on geography, but these too remained largely unaltered at the regional level. Neither did energy and feedstocks for industrial processing change much: natural gas, petroleum liquids, and coke remained dominant inputs into petrochemical, cement, steel, glass, plastic, and fertilizer production.

Nuclear reactors have generated roughly 20 percent of the nation’s total electricity generation, at just over 50 sites around the country, for decades. But due to both environmentalist opposition and particularly acute regulatory constraints, the expansion of the US nuclear sector effectively stalled after the 1970s. In 1974, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission replaced the Atomic Energy Agency and in its nearly 50 years of existence has issued precisely one license for a new nuclear reactor that successfully entered commercial operation.4

The nuclear sector’s stagnation was further assured by electric power market deregulation. Over the course of the 1980s and 1990s the environmental, consumer watchdog, and utility industry communities together pushed a shift towards liberalization of electricity markets in the United States. This led to a breakup of traditional integrated electric power generation monopolies, and the ratepayer-financing model that had underwritten power plant construction up to that point.5 These reforms were intended to open the market up to smaller, independent power producers. One outcome of liberalization was the development of hundreds of relatively small, flexible natural gas power plants. Meanwhile, without ratepayer and low-interest public debt financing, large capital-intensive power plants, including nuclear plants and hydroelectric dams, became harder to build.6

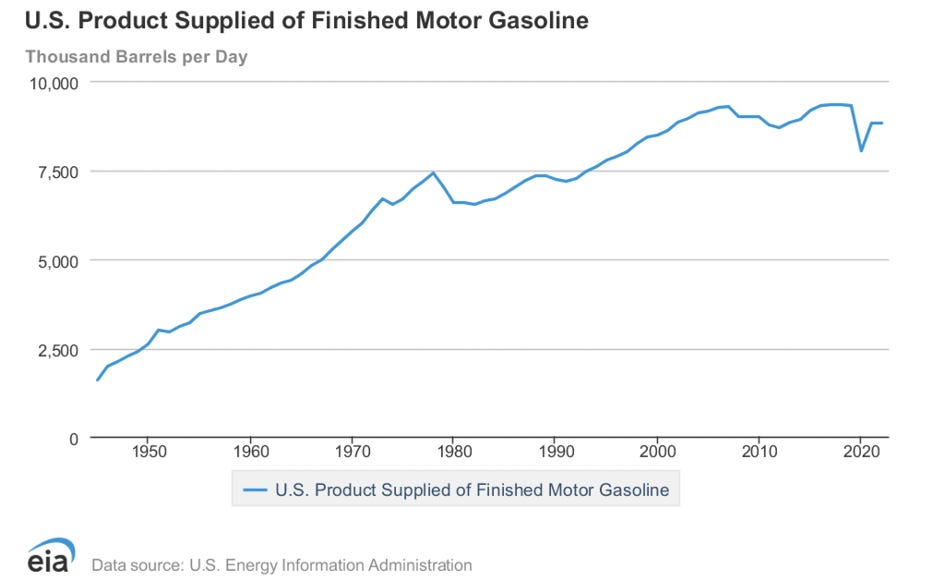

Throughout this period, petroleum products continued to fuel the overwhelming share of US light-duty, heavy-duty, aviation, shipping, rail, and marine transportation. Shifting consumer preferences have led to rising average vehicle size and weight in the light-duty automobile fleet. This trend has largely canceled out the impacts of efficiency gains in internal combustion engine and vehicle engineering, keeping transportation fuel use relatively stable over the last twenty years.7

All the while, the United States remained a major producer of coal, oil, and natural gas, but production of these commodities did not increase meaningfully and indeed declined markedly in the case of coal. This long period of fuel stability coincided with an increasingly influential environmental movement, which advocated for pollution control policies, including the Montreal Protocol limits on chlorofluorocarbons, the Clean Air and Water Acts as well as their various amendments, and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires all major and minor construction and infrastructure projects to undergo extensive environmental analysis and, often, litigation.

Starting around 2008, four major developments pushed the American energy system into a new equilibrium.

The first was the American shale fracking revolution, under which decades of public and private R&D into unconventional oil and gas exploration finally paid off. Since 2006, domestic production of natural gas has nearly doubled and production of oil has more than doubled. This has given US producers somewhat greater leverage in globalized commodity oil markets, while dramatically altering the economics of domestic natural gas supply and demand in both the power and industrial sectors. Cheap shale gas is credited with displacing coal in the US power sector over the past two decades, and is therefore responsible for over half the reductions in electric-power carbon emissions that occurred over that period.8

The second development, largely responsible for the other half of emissions reductions, was the dramatic decline in prices of solar and wind technologies, along with lithium-ion batteries (which store electricity for electric vehicles and at the grid scale, among other applications).9 These price declines have led to impressive growth in both renewable energy and, more recently, electric vehicle penetration. These technological success stories complemented the shale revolution.

So-called variable renewable energy (VRE) sources have also benefitted from electricity market liberalization and federal tax credits as well as technology cost declines. Solar and wind plants can bid into wholesale power markets at or below a marginal cost of zero. Utilities have a strong incentive to buy the power sold by independent VRE producers, and are more often than not required to do so by state-level renewable portfolio standards (RPS). However, electric grid balance-of-system costs rise in proportion to VRE penetration, since capital-intensive “backup” power capacity must remain available for times when the wind doesn’t blow and sun doesn’t shine. Solar and wind operators do not cover these costs, which consumers ultimately pay for in the form of higher rates to cover underutilized balancing capacity, added transmission to connect geographically sensitive solar and wind farms, and other costs.10

As a result, solar and wind farms operate effectively as fuel savers for the nation’s large fleet of flexible natural gas plants, pushing wholesale power prices down but increasing the retail rates ultimately paid by consumers. This has accelerated the coal-to-gas transition, since coal plants are more capital-intensive and less flexible than gas plants. But it has also undercut the economics of nuclear power plants in deregulated electricity markets. Nuclear plants have low marginal costs but high capital costs, and many proved uneconomical when faced with artificially low wholesale electricity prices and few policy incentives for their continued operation.

The closure of nuclear power plants, either due to burdensome regulation, unfavorable economics, or both, has caused carbon emissions to rise, since shuttered nuclear capacity is reliably replaced largely by new and existing natural gas. Some states, including California and Illinois, have taken measures to keep their nuclear plants operating in recent years, while others like New York have shut theirs down prematurely.

Nevertheless, the coal-to-gas transition and the growing penetration of wind and solar have led to a peak in US greenhouse gas emissions and an ongoing absolute decoupling of US economic growth from emissions.11

The third development is the emergence of climate change as a policy priority and, crucially, the failure of the Waxman-Markey carbon emissions cap-and-trade legislation in Congress in 2010.

For years prior, and throughout the 2008 presidential campaign, energy and environmental advocates had pinned their ambitions on putting a “price on carbon” to internalize the social costs of emissions, penalize fossil fuels consumption, and set the U.S. energy sector on a path to climate stabilization in the coming decades. But increasing the price of gasoline and other fossil fuels in the wake of the Great Recession proved untenable. Mainstream climate politics and advocacy shifted towards a focus on investment-led policy, modeled partially after the clean energy investments in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2008.12

Notably, technology and infrastructure policy, not carbon emissions policy per se, were largely responsible for carbon emission reductions over this period.13 This included domestic investments like the R&D that led to the shale revolution and deployment incentives powering wind and solar’s growth, but also international forces, most especially Chinese industrial investments in low-carbon energy technologies. While U.S. oil and gas markets have become increasingly (if not absolutely) independent in the last 15 years, the domestic markets for wind turbines, solar photovoltaic panels, lithium-ion batteries, and even electric vehicles have become more and more dependent on China for both raw materials and finished products.14

This growing emphasis on infrastructure and technology policy was supercharged by the fourth key development in recent energy policy and politics: the flurry of supply-side policy interventions that followed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the global supply chain disruptions, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.15

The CARES Act, Operation Warp Speed, and the American Rescue Plan—pandemic response policies pursued across the Trump and Biden administrations—evinced an unprecedented financial and industrial policy intervention into the American economy. The Biden administration followed these up with the Infrastructure Innovation and Jobs Act (IIJA), the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act, which collectively amount to a “new green industrial policy.” Policymakers described these laws as economic rescue and national security policies as much, or more, as they described them as climate or environmental policies.

These post-pandemic pieces of legislation rode the momentum established by (a) the renewed attention of energy and environmental advocates on supply-side interventions; (b) the American shale revolution’s salutary effects on energy prices and domestic industrial activity; and (c) the proof-of-concept provided by price declines in renewables and lithium-ion batteries, which enabled new optimism for similar revolutions in hydrogen electrolyzers, advanced nuclear reactors, enhanced geothermal drilling, electric heat pumps, fully electric vehicles, and more.

If popular energy systems models are at all reliable, the recent shifts in the American energy system are only the beginning. The coming decades may witness a doubling of U.S. electricity production and consumption, as many end-uses are electrified and IRA incentives enable massive new deployments of solar, wind, nuclear, geothermal, and carbon capture facilities.16 Production of certain commodities, like hydrogen and certain critical minerals, might increase by several orders of magnitude. Deployment of electric power transmission lines and pipelines for captured carbon and ammonia is projected to double or more. Economists expect public and private investments in these massive infrastructural endeavors to exceed multiple trillions of dollars over the next two or three decades.17

The Politics of Energy Abundance and Affordability

The massive investments passed by both the Biden and Trump administrations are landing in an uncomfortable moment for global capital markets and geopolitics. Interest rates have risen steadily since the COVID lockdowns of 2020, while resilient economic demand has combined with global conflict and supply chain shocks to keep energy commodity prices high. In an era of costlier energy and material resources, high interest rates, and high deficits, neither the old emissions pricing paradigm nor the alternative investment paradigm is likely to take us much further.18

The major energy policy debates in the coming years will linger on how to keep consumer prices low, how to accommodate the trillions of dollars in subsidies for low-carbon technologies with both environmentalist and local opposition to infrastructure projects, how to reform federal and state regulatory regimes, and how to use trade and foreign policy in influence energy import and human rights priorities.

Both sides of the political aisle—either explicitly or tacitly—will continue to support domestic oil and gas production, which already benefits from a categorical exclusion under NEPA as well as a fully capitalized workforce and supply chain. While the Biden administration came into office promising to limit drilling on federal lands and otherwise discourage oil and gas development, the White House’s practical decisions have, if anything, worked in the opposite direction. The administration has granted more oil and gas drilling permits than the Trump White House had by this point,19 and the Justice Department is actively arguing against activist lawsuits to hold fossil fuel industries liable for global climate damages.20 All sides agree, at the end of the day, that abundant, affordable energy is non-negotiable.

The future of the Inflation Reduction Act, however, will depend to a significant degree on the results of the 2024 election.

Despite the hype, the IRA was anything but unprecedented. For decades policymakers have provided R&D grants, loan guarantees, project financing, tax credits, standards, and mandates for a large variety of energy technologies. The IRA largely amounts to an extension and supercharging of those supports.21

What distinguishes the IRA are the politics behind it. By the time of its passage, the law had become essentially a resurrected Build Back Better (BBB), the massive economic and social policy omnibus legislation Democrats spent over a year of the 117th Congress trying, and ultimately failing, to advance. Having already passed the bipartisan Infrastructure Innovation and Jobs Act and the CHIPS and Science Act, BBB was to include all the things Democrats could pass within the budget reconciliation process without any Republican votes. Proponents universally blamed Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), who consistently voiced skepticism of certain provisions of BBB, for its defeat. But it was reported at the time that Manchin was not the only Senator reluctant to pass BBB, just the only Senator who was vocally reluctant. Shortly after BBB died in Congress, Manchin released the text of the Inflation Reduction Act, which was ultimately passed through the budget reconciliation process.

The law was also passed under an agreement between Manchin and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) that Congress immediately take up energy infrastructure permitting reform legislation, which could not by statute be included under budget reconciliation. Manchin’s permitting reforms were vocally supported by congressional Democratic leadership and the White House but defeated in the autumn of 2022 by a combination of environmental organizations which had previously supported the IRA and Republicans uneager to provide Democrats another legislative victory ahead of the Congressional midterms.

Ongoing debates over IRA implementation have focused on domestic content requirements and tax credit eligibility, especially for green hydrogen production and electric vehicles. Both are relatively high-cost options today, and technological pathways to widespread commercial viability remain uncertain.

With the IRA, Congress simultaneously threw “the full financial might of the federal government behind the clean energy transition”22 and achieved Democrats’ “last best chance to tackle the climate crisis before it’s too late,”23 effectively capping the gushing spigot of new post-COVID federal spending. Immediately afterwards, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed Clean Air Act greenhouse gas regulations on vehicle tailpipes and power plants, regulations that advocates have described as a “backstop” on the rest of the Democrats’ carrots-heavy policy agenda.24

While some of Manchin’s proposed permitting reforms were ultimately included in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, the modesty of those reforms, in contrast to the scope and ambition of the IRA and the White House’s strong commitment to regulations on carbon emissions, reveal a Democratic coalition more supportive of incentives and regulations than sensible deregulatory policies to lower the cost of infrastructure expansion.

The permitting reform debate, then, will necessarily be a bipartisan one, in contrast to the hyper-partisan politics that led to IRA and the EPA proposals. Reform advocates on the left favor Federal Energy Regulatory Commission reform and marginal NEPA reforms that would benefit “good” renewables and transmission projects without benefitting oil and gas, pipelines, or other “bad” forms of energy development. The right, on the other hand, has oftentimes opted for more sweeping, if vague, deregulatory ideas, with prominent elected Republicans promising to “abolish” NEPA, the NRC, and the EPA.25

Finally, much of the development in both energy markets and resulting carbon emissions will come downstream from decisions about national security and geopolitics. U.S. government efforts to isolate China and Russia from global commodity markets will likely achieve mixed results. Perhaps the Inflation Reduction Act will successfully scale up American manufacturing of lithium-ion batteries and hydrogen electrolyzers, but few if any expect full economic decoupling from China. Likewise, the Western response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has proven moderately successful at identifying alternate export markets for oil, gas, and commodity crops. But Russia and China together continue to wield enormous influence in low- and middle-income countries. Tensions with China and Russia will remain one of the largest levers on energy prices and industrial competitiveness, with both positive and negative effects possible for American energy markets, carbon emissions, and consumers.

Energy Abundance and Affordability After the IRA

To navigate a post-IRA, high interest rate environment chock full of regulatory hurdles, both sides of the political aisle will have to compete, less over which forms of energy production to celebrate rhetorically, and more over how to practically meet the regulatory, practical, and financial needs of diverse technological industries.

Meanwhile, the marriage of convenience between low-carbon industries and the institutional environmentalist movement will grow more and more distant, as environmentalists’ technophobia and deeply held aversion to industrial development increasingly conflict with the need to put low-carbon steel in the ground. Industries working to take advantage of public subsidies will increasingly encounter opposition from their erstwhile environmentalist allies, who remain dedicated to protecting legacy environmental and land use regulations that obstruct low-carbon technology and infrastructure deployment.

The outlines of a new energy politics are already taking shape. The members of the so-called “abundance movement”—composed of ecomodernists, supply-side progressives, state-capacity libertarians, and free-market conservatives—are ideologically distinct but largely aligned on the goals to lower infrastructure costs and expand material abundance.26

This coalition will have different policy priorities than the ones it displaces. A forward-looking agenda to advance energy abundance in the United States will rely less on increasing public funds for favored industries and more on lowering the cost of capital and removing regulatory constraints on the commercialization and construction of energy technologies and infrastructure. Indeed, relying merely on public subsidies for clean tech without addressing regulatory barriers will most likely to result in “cost disease” dynamics, in which subsidies drive cost inflation and investments are wasted on process and procedure instead of outcomes.27

Pragmatists on all sides of this coalition should adhere to the following principles:

Pragmatic deregulation

No matter the future of the IRA, the critical constraints on clean energy innovation and deployment will come less from an absence of subsidies and more from the presence of regulatory obstacles. While the left continues to stake out proposals for narrow regulatory reform that benefit their preferred technologies and projects, popular figures on the right have demanded full abolition of the U.S. regulatory state.

Neither of these approaches will work. Increasing and improving state capacity requires shifting infrastructure development authority away from the courts and towards democratically accountable bodies. This will necessarily entail the continued operation and construction of projects that the environment left dislikes. At the same time, deregulating abundance will require an insider’s game, working within agencies and oversight committees to achieve practical, incremental institutional reform.

Friendshoring production

Full decoupling of the American energy economy from China, Russia, and other adversarial nations is impossible. The United States lacks the geological resources, supply chains, and comparative structural advantage to onshore most of the industries and technologies that are currently supplied by imports.

But strategic investment and regulatory reform can increase domestic industrial capacity to some significant degree, while American hard and soft power can continue to encourage relocation of raw materials production and industrial capacity to our allies.

The role of nuclear energy and “clean firm” generation

Electric power market liberalization and excessive regulation have wrecked the economics of nuclear power plant construction and operation in the United States. But there is near consensus among respected energy scholars, as well as elected representatives, that nuclear energy must play a large role if the nation wishes to build a low-cost, deeply decarbonized energy grid.

The commercialization and deployment of a new generation of smaller, advanced nuclear reactors will depend on a number of major policy reforms, starting with substantial reforms to the reactor licensing and permitting procedures at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

Nuclear is not the only “clean firm” (non-variable) electricity source available. Deep-earth geothermal and natural gas plants with integrated carbon capture can also play important roles in the decarbonized energy systems of the future, and each will require regulatory changes of their own for successful commercialization.

With potentially trillions of subsidies already flowing to solar and wind over the coming decades, pragmatic policy advocates would do well to pay more attention to these crucial, reliable sources of energy in the future.

Bottom-up techno-optimism

The realization that consumer energy prices and carbon emissions are largely downstream of technology and infrastructure policy, combined with dramatically improved computational modeling capabilities, has led many scholars and policymakers to construct elaborate energy systems forecasts and work backwards to design climate and energy policies that can meet those forecasts. These dynamics are largely responsible for the passage of the IRA, as well as the proposed EPA tailpipe and power plant rules.

We can already see the risks of “aiming” technology policy at particular modeling outcomes and forecasts, including the over-subsidization of mature technologies like solar photovoltaics and onshore wind, the attempted creation of a large green hydrogen production system before the modeled demand for hydrogen has materialized, and the political backlash to subsidizing the consumption habits of the wealthiest Americans, as in the case of subsidies for high-end electric vehicles.

But this is not how the nation’s existing, abundant, dynamic energy systems were built. A better approach would be to encourage nascent low-carbon energy technologies through nimble and pragmatic investment and regulatory policies, design for eventual subsidy independence, and work along the way to improve infrastructure siting coordination, bolster supply chain resilience, and achieve cost declines across the value chain.

Alex Trembath is the Deputy Director of The Breakthrough Institute and the co-director of Breakthrough Generation, the institute’s annual policy fellowship program.

Ashley Nunes is Director of Federal Policy, Climate and Energy, at The Breakthrough Institute, and holds academic appointments in the Department of Economics, at Harvard College, and in the Labor and Worklife Program, at Harvard Law School.

Ted Nordhaus is the Founder and Executive Director of The Breakthrough Institute, and co-author of An Ecomodernist Manifesto.

Jenkins, Jesse, Devon Swezey, Yael Borofsky, H. Aki, Z. Arnold, G. Bennett, C. Knight et al. "Where good technologies come from: Case studies in American innovation." Breakthrough Institute, December (2010).

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “September 2023 Monthly Energy Review.” https://www.eia.gov/totalenergy/data/monthly/pdf/sec1.pdf.

Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser and Pablo Rosado (2022) - "Energy". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. https://ourworldindata.org/energy.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. “Nuclear Regulatory Commission approves construction of first nuclear units in 30 years.” March 5, 2012. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=5250.

Hirsch, Richard F. Power Loss: The Origins of Deregulation and Restructuring in the American Electric Utility System. The MIT Press. 2002.

Angwin, Meredith. Shorting the Grid: The Hidden Fragility of Our Electric Grid. Carnot Communications, 2020.

Christopher R. Knittel, 2011. "Automobiles on Steroids: Product Attribute Trade-Offs and Technological Progress in the Automobile Sector," American Economic Review, American Economic Association, vol. 101(7), pages 3368-99, December.

King, Loren, Ted Nordhaus, and Michael Shellenberger. “Lessons from the Shale Revolution: A Report on the Conference Proceedings.” The Breakthrough Institute. April 2015. https://s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/uploads.thebreakthrough.org/legacy/images/pdfs/Lessons_from_the_Shale_Revolution.pdf.

Max Roser (2020) - "Why did renewables become so cheap so fast?" Published online at OurWorldInData.org. https://ourworldindata.org/cheap-renewables-growth.

Trembath, Alex and Jesse Jenkins. “A Look at Wind and Solar: Part Two.” The Breakthrough Institute. May 2015. https://thebreakthrough.org/issues/energy/a-look-at-wind-and-solar-part-2.

Hausfather, Zeke. “Absolute Decoupling of Economic Growth and Emissions in 32 Countries.” The Breakthrough Institute. April 2021. https://thebreakthrough.org/issues/energy/absolute-decoupling-of-economic-growth-and-emissions-in-32-countries.

Nordhaus, Ted and Michael Shellenberger. “Obama’s Energy Revolution.” The Breakthrough Institute. June 2013. https://thebreakthrough.org/issues/energy/obamas-climate-pragmatism.

Lovering, Jessica and Ted Nordhaus. “Does Climate Policy Matter?” The Breakthrough Institute. November 2016. https://thebreakthrough.org/issues/energy/does-climate-policy-matter.

Atkinson et al. “ “Rising Tigers, Sleeping Giant: Asian Nations Set to Dominate the Clean Energy Race by Out-Investing the United States.” The Breakthrough Institute and Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. November 2009. https://thebreakthrough.org/articles/rising-tigers-sleeping-giant-o.

Trembath, Alex et al. “Saying the Quiet Part Out Loud: Quiet Climate Policies in a Post-COVID World.” January 2021. https://thebreakthrough.org/articles/saying-the-quiet-part-loud.

Jenkins, J.D., Mayfield, E.N., Farbes, J., Schivley, G., Patankar, N., and Jones, R., “Climate Progress and the 117th Congress: The Impacts of the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act ,” REPEAT Project, Princeton, NJ, July 2023. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.8087805

Bistline, John, Neil R. Mehrotra, and Catherine Wolfram. 2023. “Economic Implications of the Climate Provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act.” BPEA Conference Draft, Spring.

Nordhaus, Ted and Alex Trembath. “On the Difference Between Techno and Technocratic Optimism.” The Breakthrough Institute. July 2023. https://thebreakthrough.org/issues/energy/on-the-difference-between-techno-and-technocratic-optimism.

Joselow, Maxine. “Biden is approving more oil and gas drilling permits on public lands than Trump, analysis finds.” The Washington Post. December 6, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/12/06/biden-is-approving-more-oil-gas-drilling-permits-public-lands-than-trump-analysis-finds/.

Nilsen, Ella. “Biden is campaigning as the most pro-climate president while his DOJ works to block a landmark climate trial.” CNN. August 9, 2023. https://www.cnn.com/2023/08/09/politics/biden-juliana-youth-climate-trial/index.html.

Trembath, Alex. “Joe Manchin: Climate Hawk.” The Breakthrough Institute. August 2, 2022. https://thebreakthrough.org/blog/joe-manchin-climate-hawk.

Jenkins, Jesse. “How the Climate Fight Was Almost Lost.” Heatmap News. August 18, 2023. https://heatmap.news/politics/inflation-reduction-act-jesse-jenkins.

“Why This Is Our Last Best Chance for Meaningful Climate Action.” Evergreen Action. February 4, 2022. https://www.evergreenaction.com/blog/why-this-is-our-last-best-chance-for-meaningful-climate-action.

Bush, Evan. “Biden administration’s power plant rules underscore reality of EPA limits.” NBC News. May 12, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/science/environment/biden-administrations-power-plant-rules-underscore-reality-epa-limits-rcna84201.

Mackenzie, Aidan, Arnab Datta, and Alec Stapp. “A Grand Bargain for Permitting Reform.” The Institute for Progress. September 29, 2023. https://progress.institute/a-grand-bargain-for-permitting-reform/.

De Rugy, Veronique. “An Abundance Agenda Can Restore Our Economy, Revitalize Our Society, and Bring Our Country Together.” The Mercatus Center. April 2023. https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/abundance-agenda-can-restore-our-economy.

Trembath, Alex. “Cost-Disease Environmentalism.” City Journal. March 5, 2022. https://www.city-journal.org/article/cost-disease-environmentalism.