Politics is One Giant Culture War

Polling across 20 countries shows how cultural battles over identity, patriotism, and national values fuel political divides.

For most of the 1980s and 1990s, politics in Western nations was fought over different conceptions of state power, taxes, regulation, and redistribution. Conservative parties mostly favored more capitalism and less regulation while progressive parties mostly favored market interventions and more generous social welfare policies. Post 9/11, parties began to divide along issues of military interventions and the global war on terror, with contentious issues around immigration also rising in importance. But for most of the past 40 years, a basic left-right dichotomy focused on the proper balance between state and private power dominated much of politics in democratic and capitalist nations.

Around 2012, something fundamentally shifted with this basic left-right ideological conflict, particularly in the U.S. but also in other Western democracies.

Cultural battles around religion, gender, race, and other social issues have always played a role in politics. But during President Barack Obama’s second term—with the rise of social media, the Brexit vote in the U.K., and the ascendance of Donald Trump to the presidency in 2016—the main debates in politics moved sharply away from economics and state power and towards competing visions of identity, patriotism, immigration, and perceptions of cultural extremism.

Some of these divides are explained by educational shifts in the composition of party voters, with more culturally traditional working-class voters moving towards conservative and populist right parties and more educated professional voters moving into progressive and green parties.

Yet educational polarization doesn’t explain why today you can find many Trump and Biden voters agreeing (at least in polls) about the importance of jobs or stronger economic support for workers and families while simultaneously viewing one another as mortal threats to our nation’s identity and future well-being.

How did culture and identity come to be the defining line in much of global politics?

The primacy of cultural politics becomes clearer when examining results from a major cross-national study of public opinion in 20 countries—with more than 22,000 respondents—conducted by YouGov and Global Progress, along with help from TLP as featured in an earlier post.

Our study asked citizens in respective countries to choose which one of two statements comes closer to their own view, labeled here but not in the survey as left-wing and right-wing illiberalism:

We need to be vigilant against groups trying to impose new cultural values and views about religion, gender, immigration, or race that don’t reflect our society’s traditional values. (Left-wing illiberalism)

We need to be vigilant against groups that undermine democracy by attacking judges, questioning election results, and promoting societal unrest based on conspiracy theories, racism, and anti-scientific claims about vaccines and climate change. (Right-wing illiberalism)

As seen in the chart above, by a slight 48 percent to 36 percent plurality, citizens across all 20 nations say right-wing illiberalism is a bigger concern than left-wing illiberalism when forced to choose. Notably, these results are consistent across demographic lines. For example, pluralities of voters from Generation Z to the Silent Generation express more concern about right-wing illiberalism than left-wing illiberalism, as do pluralities of lower-, middle-, and higher-educated citizens across all nations surveyed, and both men and women across these nations.

So, traditional demographic splits that define politics in many countries don’t correspond to divides on these important cultural issues around democracy and identity. But looking at the results cut by ideology and party voting—overall and in the U.S., the U.K., and Germany, specifically—we find some fascinating and concerning trends:

(1) Across all nations tested, pluralities or majorities of voters self-identified as “very left-wing” to “slightly right of center” express more concern about right-wing illiberalism than left-wing illiberalism—consistent with the overall pattern. In contrast, majorities of citizens identifying as “fairly right-wing” or “very right-wing” say that cultural leftism is a bigger concern. In the center and center-right we tend to see more mixed concerns about both types of extremism.

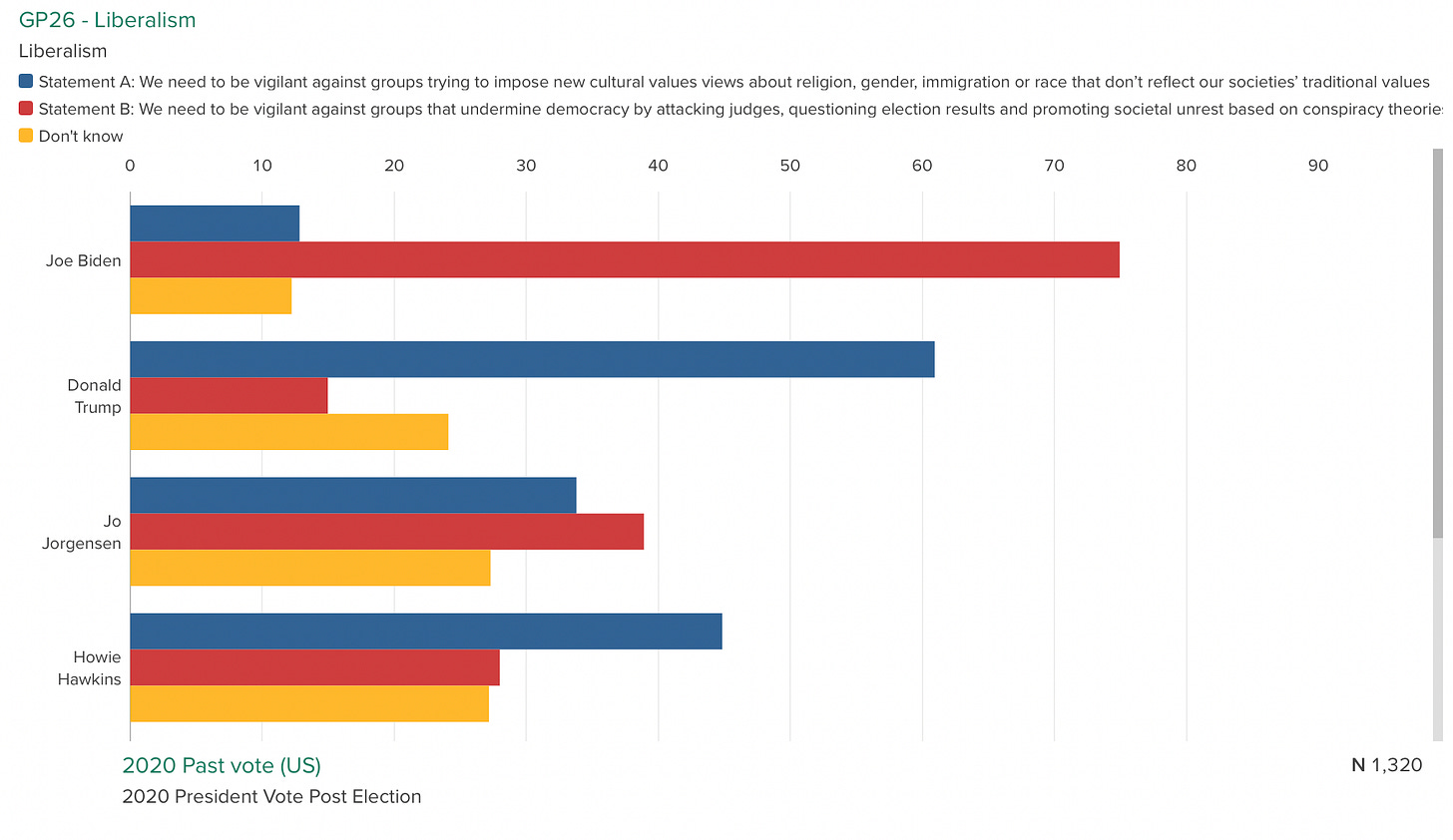

(2) However, in the United States, the cultural and ideological divide is far more pronounced translating into more than 7 in 10 Biden voters expressing greater concern about right-wing illiberalism than left-wing illiberalism, with more than 6 in 10 Trump voters expressing the exact opposite view.

(3) In the United Kingdom, the divisions are somewhat less stark than in the U.S. with pluralities of Conservative voters along with majorities of Labour, Liberal Democrat, and SNP voters worried more about right-wing extremism than the left-wing version. But 6 in 10 Brexit Party supporters, along with more than 4 in 10 Tories, express more concern about cultural left influence on society than the right-wing version.

(4) In Germany, responses are somewhat more consistent across groups with majorities of voters from all major parties—including the CDU/CSU, SPD, Die Linke, the Greens, and the FDP—focusing their concerns on right-wing illiberalism over left-wing illiberalism. In contrast, more than 6 in 10 Alternative for Germany (AfD) voters worry more about cultural leftism.

Overall, these findings tell us that the main political divisions in many Western nations today—and in the United States, especially—focus more on fundamental issues of national identity and cultural beliefs rather than things like proper tax rates or health care expenditures. Many voters across demographic and even partisan lines can find some agreement on important economic and social welfare policies. What citizens can’t agree on at all is what their countries mean and stand for today—and who is included in this vision.

The main question emerging in contemporary politics is ominously: “Who poses the bigger threat to society: the cultural left or the far right?” Where a person comes down on this question increasingly determines which parties or candidates they will likely support.

The problem for democracy and the health of our societies is apparent.

Political debates centered on sectarian battles over who is the bigger threat to the nation never turn out well. So, it’s incumbent upon center-left and center-right forces to push back hard against both kinds of ideological illiberalism to define a new vital center that is “pro-worker, pro-family, and pro-nation” while also being pluralist and culturally moderate.

If the center does not hold, expect our societies to further fracture and divide—or worse, descend into a cultural cold war that undermines political stability and encourages mutual loathing among citizens.