Political Sectarianism Makes America its Own Worst Enemy in the World

U.S. foreign policy tribalism confuses the American public and creates openings for America's competitors in the world

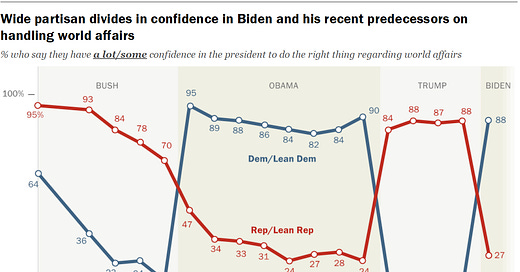

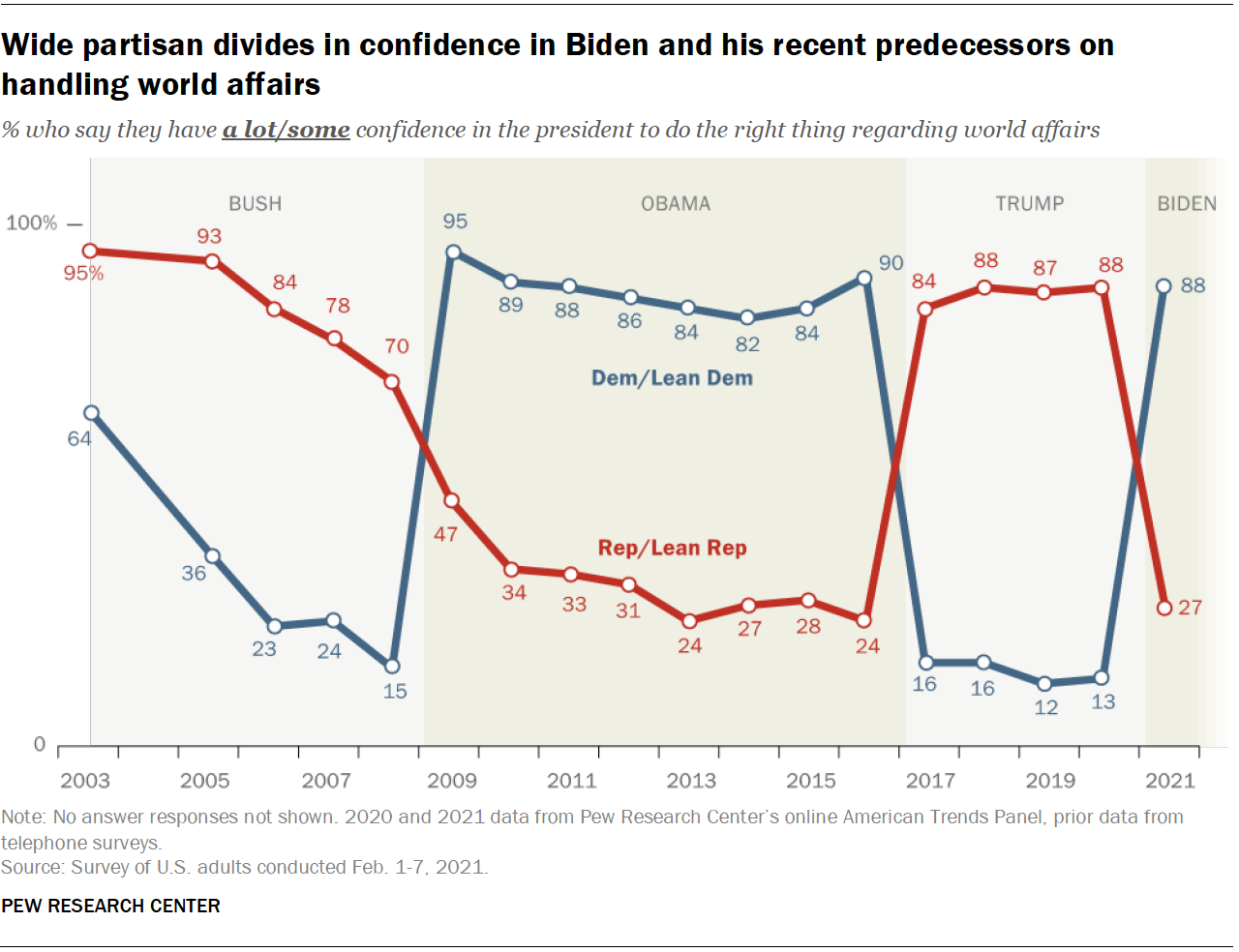

Take a close look at this graph from an excellent study of U.S. public opinion on foreign policy by the Pew Research Center, conducted just about a week into the new Biden administration. It depicts an important story of the past twenty years. Public attitudes on foreign policy have become just like almost every other issue in political and cultural life in America: sharply divided.

That’s no surprise in a country where partisan rage has been the fuel propelling political and cultural elites to debate almost every single aspect of American life through the lens of hyper-partisanship: children’s books, sports, fast food burgers, sneakers, the Christmas holiday, and so on.

You name it, and “thought leaders” and politicians in America will find a way to use the media to signal a virtue and stake out a claim in the never-ending debate about who we are. There are increasing signs that this “us versus them” sectarianism is exhausting most Americans and leading them to disengage from public life or withdraw into their own worldview bubbles.

As you can see from the graph, these sharp partisan divides are not a new thing on foreign policy. At the time the poll was conducted, just a few days into Biden’s time in office, Democrats and Republicans had already started to draw conclusions and split into their usual corners.

That’s a bad thing for America in the long run because these sharp divisions are exploited by the country’s adversaries and enemies. Also, most Americans these days don’t really follow a lot of the things foreign policy elites vociferously debate on think tank panels or in social media because they are more focused on things relevant to their own lives: jobs and basic security. The ordinary American is rationally ignorant and apathetic about most of the issues that raise the pulses of the country’s sharply divided foreign policy elites.

How did we get to this place of such sharp political divisions on foreign policy? Here are five key phases and markers from the past two decades:

1. 2002-2004: Republicans use the “war on terror” frame to paint Democrats as unpatriotic and weak on security.

2. 2005-2008: Democrats use the Iraq war, which became the top political priority for voters in the 2006 mid-term elections, to argue that Republicans are incompetent war mongers.

3. 2009-2012: The Great Recession leads to a sharp inward focus in America’s politics, and the GOP starts to become sharply divided over the politics of national security with neo-isolationist libertarians, traditional establishment security Republicans, and neoconservatives duking it out.

4. 2014-2016: An immigration crisis on the southern border, the rise of ISIS in the Middle East, and challenges from Russia and China in the world lead to a re-emergence of the politics of fear on the right. Obama’s two terms produce further strategic narrative drift. Trump’s angry nationalism mows down the divided GOP, and Democrats start to see their own internal divisions with challenges from the so-called progressive left (a movement that has largely crashed and burned in 2019-2021, but more on that later).

5. 2017-Present: The strategic narrative drift and era of division and dysfunction continues. Attitudes among Republican voters on things like Russia shift strangely towards the more positive, and some Democrats rediscover democracy and human rights after years of its downgrading in America’s story.

The sum total of this trajectory has left America sharply divided on most national security questions, with incentives from the media environment and funding for foreign policy thought leaders doing more often to incentivize division rather than forge national unity.

Debate and diversity of ideas are a good thing for America’s foreign policy IF the discussion is conducted on the level in good faith and seeks to keep the bigger picture of what’s going on in the world and what the American public wants in mind. But that’s often not the case these days.

The current foreign policy tribalism is a major strategic liability for America that is exploited by the country’s adversaries and competitors like China, Russia, and Iran, who actively sow division and confusion within America’s internal debates. The intended effect is to either induce strategic paralysis or advance their own country’s agenda in some specific areas. It also confuses America’s allies and partners, who continue to worry about how the election cycles and erratic pendulum swings in policy will affect their own interests.

Lastly, this dysfunctional and toxic political environment on national security mostly ends up confusing the American public, who mostly don’t understand what a lot of noise is all about in U.S. foreign policy circles.

There’s no simple remedy to this situation. America may be stuck in a moment it can’t get out of for now. Divisions on the left and the right that emerged in the previous decade are likely to be a chronic condition, and as a result the spectrum of views on U.S. foreign policy isn’t what it used to be. The old camps are jumbled, but new ones haven’t yet fully coalesced.

One silver lining is that the Biden administration is off to a decent start on these issues, and it is headed by a president who knows a lot about the world.

America has a lot of work to do in shaping a new, inclusive national narrative. Failing to construct this new narrative will prevent the country from achieving its full potential in the coming post-COVID-19 world.