Partisan Sectarianism is Wrecking America

The two-party system isn’t going away anytime soon. We need more ideological diversity within the parties and a willingness on Americans' part to lower the temperature.

Every week, more stories emerge spotlighting the seemingly unbridgeable partisan gaps between Americans. The stories are much the same in rural, suburban, and urban environments: people who support one party, leader, or cause—or strongly oppose some action of government—getting increasingly aggressive and hostile towards opponents and even resorting to violent confrontations in extreme cases. Stories abound of families and friendships breaking apart over politics as civil discourse evaporates across political institutions and in the media.

Some of these stories are overblown, of course. Many Americans understandably have checked out from politics altogether and don’t have the time or interest to discuss national matters, let alone fight with others about arcane ideological disputes and conspiracies surfacing online.

But there is concerning evidence over time that democratic legitimacy is under threat internally from different groups of Americans—Trump voters on one side, Biden voters on the other, and various factions within each—who genuinely hate one another and refuse to accept the normal ebb and flow of governmental control changing partisan hands.

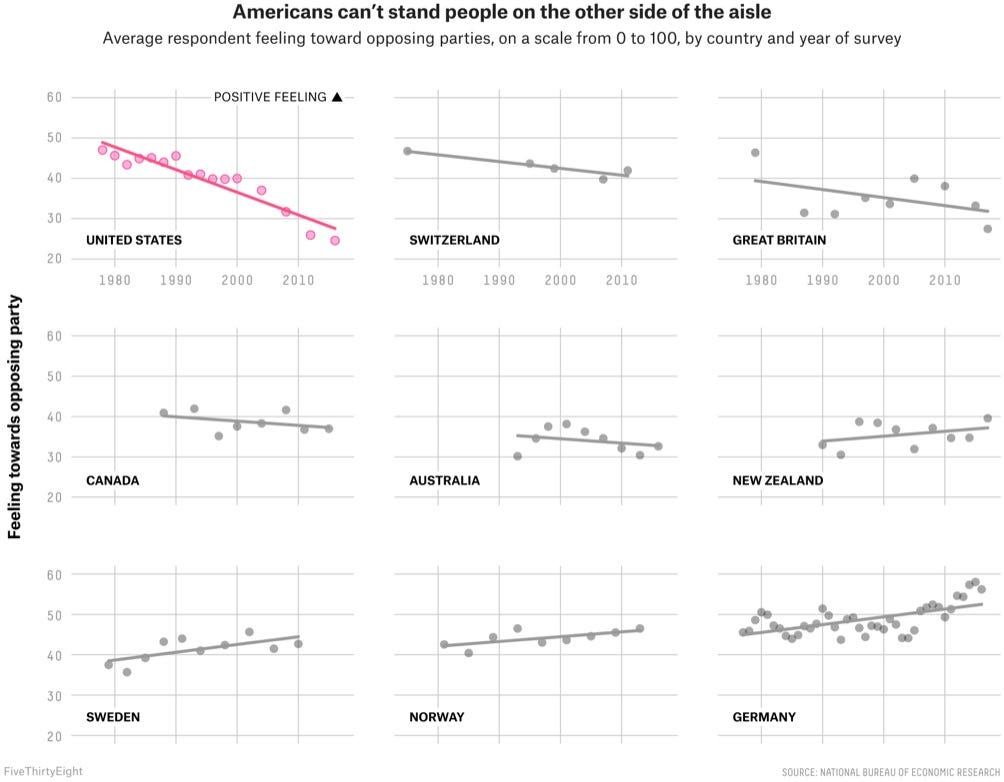

Political scientist Lee Drutman has been covering this issue for some time and highlighted some stark comparative data for FiveThirtyEight, based on a 2020 paper from economists Levi Boxell, Matthew Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro, about America’s unique partisan sectarianism compared to other democracies. The graphic below from Drutman shows the massive decline in Americans’ positive feelings towards opposing parties since the 1980s, a trend called “affective polarization” that is not seen as prominently in many other leading economies.

These data aren’t perfect due to some question wording differences, but they do highlight a genuine challenge for American politics: How can Americans continue to govern themselves and uphold democratic rights for all if they increasingly see people from the opposing party as their enemy, and not just people they disagree with about candidates and policies?

And more importantly, what should we do about it?

Drutman is a strong proponent of proportional representation to reduce the distorting impact of two-party systems that force people with multiple or inconsistent views into one or another party and then encourage all-or-nothing ideological battles between the two. Multiparty democracies can be contentious and chaotic as we’ve seen recently with elections in Israel and other countries that fail to produce consensus or stability in government. But they also drive parties to compete for votes across geographical and demographic lines, and the process of forming coalition governments can help to temper extremes and encourage people to compromise and work together without taking everything personally.

Unfortunately, despite any advantages of such a system, proportional representation is not likely to be taken up in America anytime soon given the multiple hurdles of changing electoral rules and party biases towards the status quo and their own power.

So, it will be up to Americans and the two-parties themselves to figure out how to turn down the heat on our toxic politics, check the extremes, and try to create more reasonable pathways for consideration of national and local needs. If we can’t create a multi-party system, we can at least try to mimic the positive contributions of one within our two-party structure.

First, we need to encourage more ideological and viewpoint diversity within the Republican and Democratic parties and devise institutional means for representing these competing voices while working across ideological lines on pragmatic economic and social policies. There are precedents for this with civil rights legislation and the creation of Medicare during the 1960s—and tax and immigration changes during the 1980s—that passed with crossover support from liberal Republicans or conservative Democrats, respectively. Major changes today, such as the passage of the Affordable Care Act or the 2017 Trump tax cuts, occur almost exclusively with one-party support and then the opposing party going to the mat for multiple election cycles to erase the legislation.

The bipartisan infrastructure bill in 2021 showed a possible way to encourage ideologically diverse groups to work together to achieve something that benefits all Americans. And we may yet see more of this on policies to combat Russia’s flagrant aggression and on electoral reforms. But ideological diversity within both parties will be required to engage and broker these and other compromises. Larger blocs of divergent groups of legislators within each party will also reduce the excess power any one person has over policy making and could help to limit governing by crisis where Congress makes huge decisions at the last minute with gigantic bills few people understand.

Second, Americans themselves need to find ways to make partisanship and group differences less central to their own identities. It’s a fundamental norm in liberal democracies that the government and individual citizens can’t force other people to bend the knee to one particular way of thinking. Pluralism and tolerance of dissent are vital to healthy democracies. People need to respect different values and beliefs and give people a fair hearing, or at a minimum avoid going bonkers with illiberal ideas when their side loses an election.

More importantly, Americans would do well to find more cooperative local projects to work on together—fixing schools, cleaning up neighborhoods and keeping them safe, getting to know others from different backgrounds and faith traditions, helping those most in need—rather than constantly retreating into partisan echo chambers and looking for more ways to despise other Americans.

We can’t eradicate partisan sectarianism overnight. But we can take steps to institutionally encourage more viewpoint diversity in the two-party system and “deradicalize” our own partisan politics by refusing to live based on animosity towards others.