Neo-Orientalism degrades the quality of U.S. debates on the Middle East

How domestic policy advocacy overtook analysis and spread like a virus into the policies of several recent U.S. administrations

The Liberal Patriot has focused much of its attention on the divisions affecting America’s society and looking for pathways to build a new sense of common purpose and shared idea of what the country can do together. Most days this seems like a quixotic undertaking, the triumph of hope over the bitter daily experience of division and dysfunction that afflict the country.

But it’s part of what I view as the real forever war – the battle done every day to defend open debate, support inclusive political orders, and counter the illiberal forces of ideological tribalism on the right and the left that contribute to fragmentation and disunity.

It’s an intellectual and political challenge, but it’s also a personal challenge, too. Finding ways to treat your intellectual and ideological rivals with respect and remaining open minded and receptive to different perspectives is a hard thing to do when the algorithms of social media and the daily rhythms of cable television push us apart. It’s sometimes difficult to do with people you live or work with every day given the nature of how our current media and political environments incentivize tribal division and interpersonal discord. The tone that’s set at the top of our country and institutions matters quite a lot, and that tone is all too often not focused on the greater good.

The main reason why it’s important to try to have a more civil dialogue is that our individual perspectives are limited on their own and we can gain greater insights and find new pathways forward if we aim to have on the level, honest exchanges of different views. The sum can be greater than its individual parts, but only if we conduct our discussions in ways that widen rather than narrow our collective field of vision.

One arena where this ideal for a debate that’s on the level is particularly challenging: U.S. policy in the Middle East, which has become increasingly caustic and less insightful than in years past. Some of this has to do with the difficult and complicated topics involved and the growing perspectives that are hard to mediate. Some of it is the human factor of different personalities.

Adding to the complications: a recent trend to oversimplify dynamics in the Middle East and project America’s own way of thinking and domestic politics into policy recommendations that ignore the complicated realities of those societies.

After 9/11, many people asked, “why do THEY hate us?” Some responded by projecting a “Freedom Agenda” with recommendations for holding quick elections in the middle of civil wars. More recently, we’ve seen cynical shoulder shrugs on the left who find it hard to summon deeper lessons than ones mostly linked to the level of America’s military involvement.

There’s a paucity of creative thinking and an oversupply of social-media driven advocacy campaigns. All of this adds up to very little in terms new insights based on their actual connection to political dynamics in countries of the Middle East.

Neo-Orientalism’s impact on U.S. policy in the Middle East

An important factor has infected America’s Middle East policy debates on the left and right: neo-Orientalism, or the willful ignorance or indifference towards the actual realities of the Middle East and its people in order to advance agendas and score points in America’s domestic political debates. If you look carefully in current debates on any given Middle East issue, like Iran, Israel, Palestine, Syria, or Yemen, there’s often a missing piece in the debate: the views of the people from those places, in all of their full complexities. Instead, these countries and their people are used as props in U.S. domestic politics and advocacy-driven debates.

A recent example of this was cited by Peter Henne: some voices cited reports of a new Iran-Saudi dialogue as evidence that the “new,” more distanced position of the Biden administration on the Middle East was “working” to force the two countries to talk with each other. Henne rightly points out that this is little more than advocacy roosters taking credit for the dawn and that perceptions that the United States was looking to pull back from the region weren’t new. But that didn’t stop writers from passing the notion around in Tweets and articles.

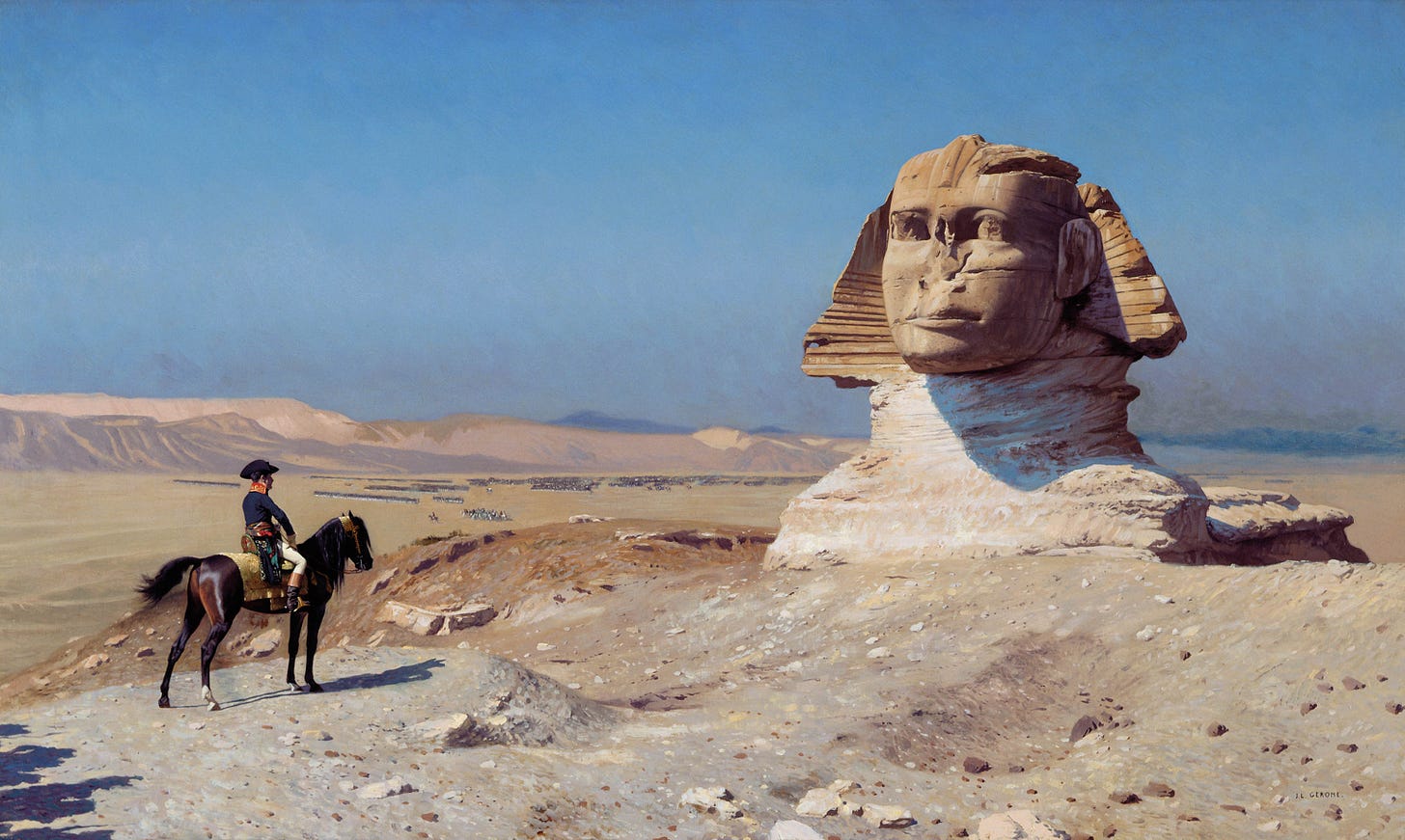

Orientalism traditionally simply defined Western study of "the East," in particular the Arab and Islamic worlds. But in the late 1970s, the term was redefined and popularized by the late Palestinian-American literary critic Edward Said, who identified the predominance of self-serving authority presumed in the power to define, name and “know” another people and culture.

In thinking about this dynamic of Neo-Orientalism and its impact on current U.S. debates on Middle East policy, I had a series of conversations and exchanges with Hussein Ibish, a thinker who knew Said personally and has a deep knowledge of his writings.

Ibish explained to me that Said’s writings:

“specifically associated Enlightenment and modern academic and cultural Orientalism as a tool and expression of colonial power. Real knowledge served the actual interests of imperial and colonial projects in the Middle East. And limited, blinkered or arbitrarily imposed definitions and conceptualizations, by being linked directly to that colonial power, imposed themselves on peoples for whom they often had no meaning and a mixed or even largely negative effect. The West spoke about and for the Orientals, which, according to Said, deprived them of the ability to speak for and represent themselves.”

Sound familiar? If you take a casual glance around some of the prominent voices on U.S. policy in the Middle East these days, you’ll find a lot of people who spend a great deal of time on social media explaining what’s going on in Iran or Saudi Arabia, even if they don’t speak Arabic or Persian or haven’t visited the country all that much.

A form of neo-Orientalism has grown in prominence in Middle East policy debates in recent years, fueled by the changing ways the media frames political and policy choices and the way social media shapes and distorts our discourse.

Neo-Orientalist thinking in America’s policy debates provides important insights into the political, social and even psychological forces operating inside of the United States. This phenomenon focuses less on the people and problems of the Middle East than on other issues and concerns that preoccupy the thinking and writing of a number of experts and analysts.

The most important feature of neo-Orientalism is the way it projects America’s own domestic political debates onto the complicated screen of Middle Eastern politics, policies, and societies, often without much reference to or direct contact with the people, governments, and key voices of and in the region.

Like traditional Orientalism, it imposes agendas, definitions and reference points that resonate strongly in, and serve the interests of domestic US politics but have little or nothing to do with the actual interest, perceptions and needs of the peoples of the region. It frequently purports to speak for or act on behalf of these peoples without bothering to examine their own views, opinions, or interests.

Today, neo-Orientalism in U.S. policy in the Middle East consists of five main features:

1. A neglect of the lives and experiences of people in the Middle East. Neo-Orientalists often speak over the people of the region rather than actively listen to them – they use governments and countries as ideological props in America’s domestic debate. At times, some voices in the U.S. policy debates proclaim great concern and sympathy for the people of the region, while remaining largely indifferent to the diversity of backgrounds and perspectives within particular countries and societies. This leads neo-Orientalists to frequently recommend politics and policies that they’d never accept at home, such as pushing liberal and democratic voices to compromise with violent and illiberal political forces for the sake of stability.

2. An inclination to frame current political challenges and conflicts as rooted in “ancient hatreds.” Neo-Orientalists tend to frame the Middle East’s contemporary problems as originating in ancient and primordial enmities between religious or ethnic groups. Former Republican vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin spoke for some on the political right when she characterized Syria’s civil war as a “yet another centuries-old internal struggle” and said the United States should “let Allah sort it out.” Likewise, President Trump justified his announced 2019 withdrawal of U.S. troops from Syria saying, “Let someone else fight over this long blood-stained sand.” Such sentiments aren’t limited to the right, however: in his 2016 State of the Union address, President Obama claimed that “The Middle East is going through a transformation that will play out for a generation, rooted in conflicts that date back millennia.”

3. Language and sloganeering drawn from advocacy campaigns. Another central feature of neo-Orientalism is its primary fixation on affecting America’s political and policy debates, which quite often does not equal presenting viable and pragmatic policy solutions to the challenges facing the nations and people of the Middle East. Slogans like “end endless war” and the formulations such as “no military solutions” are signposts of neo-Orientalism on the road ahead. Note how in recent months the advocacy language of “forever wars” has seeped into the Biden administration’s rhetoric. Will this help bring peace to places like Afghanistan or Yemen? The answer is all too frequently ignorance and apathy: few people know or care to answer that question.

4. An obsession with the role of the United States to the detriment of other factors. Neo-Orientalists place an overwhelming emphasis on U.S. policy as the main – if not sole – driver of events in the region, often with a strong bias against U.S. involvement and engagement, but sometimes also in favor of involvement narrowly defined in military terms. As a result, they overestimate the importance of political debates at home over the various policy tools employed by the United States. More fundamentally, however, neo-Orientalists deny agency to the people, governments, and institutions of the Middle East. They often evince magical thinking about U.S. power and influence in the region, with some progressives, for instance, believing that cutting off U.S. security assistance to the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen will bring that country’s internal conflict to an end.

5. A strong focus on U.S. political dynamics. Beyond from the over-emphasis on U.S. policy tools, neo-Orientalists preoccupy themselves with domestic U.S. political dynamics. They relish the opportunity to use the Middle East’s conflicts or particular policy moves by countries in the region as weapons in domestic political debates aimed at undermining their political or ideological opponents. This dynamic has its roots in the politics of foreign policy during the Cold War and was already underway in the Bush and Obama administrations, but was put on steroids during the Trump years.

Like many challenges facing America today, the problems of the Middle East and how to achieve a more balanced and constructive policy approach are too complicated for the vessels in which most dominant political and media debates occur. The incentives are too strong to retreat into shouting matches and ideological tribalism and sectarianism, and that is not likely to end anytime soon.

But individual thinkers can make a difference in small ways if they take the time to embrace the complexities and step out of their own comfortable bubbles. Take the time to listen and learn from others and have those different views shape your thinking. When the pandemic is over, actually travel to these countries and meet and interview a wide range of people.

It won’t stop the fragmentation and the oversimplifications that dominate the debates in America these days – but it may build new relationships and spark new ways of thinking that could make all the difference for producing progress in the long run.