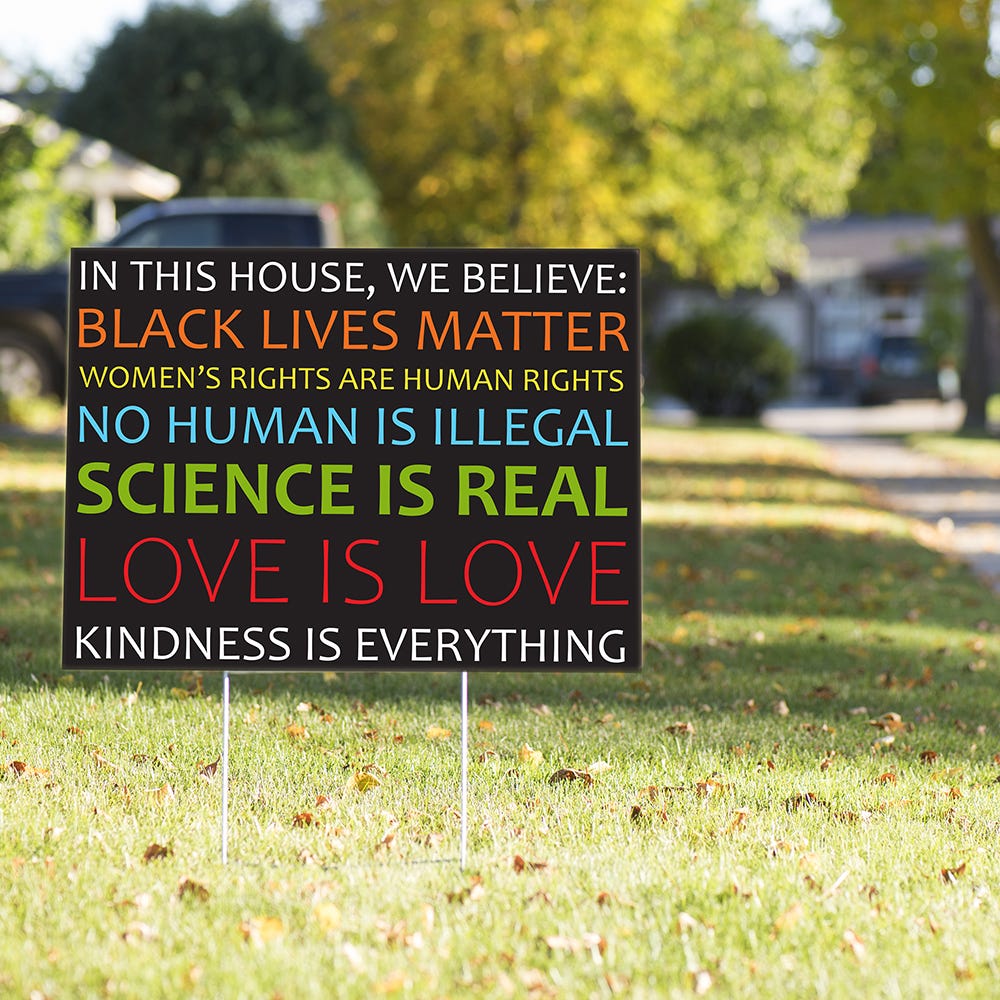

If you’ve traveled through any moderately-sized metropolitan area in America lately, you’ll probably have noticed rainbow-hued statements of faith sprouting up on well-manicured lawns across the country. These lawn signs constitute the Nicene Creed and shahada of the new religion of progressive politics that’s burst into public consciousness over the past five or six years. It’s a faith that’s rapidly won converts at the highest levels of American politics and society – one that uncannily mirrors much of the thinking and many of the practices of its ancient predecessors, complete with its own dogmas, heresies, and rituals as well as apocalypses and forms of mysticism.

This observation is neither original nor novel. Other commentators like the linguist John McWhorter and the sociologist Musa al-Gharbi have made this case convincingly, especially when it comes to anti-racism. As central as anti-racism may be to the progressive catechism, however, it’s become increasingly clear that this new political religion cannot be reduced to this one core tenet. To better understand this emerging faith in all its facets, we need to take a wider field of view that goes beyond a singular if understandable focus on anti-racism.

Before we look at this new religion’s basic articles of faith, however, it’s worth some tentative speculation about its origins. Its emergence coincides with a massive public retreat from traditional organized religions like Christianity over the past decade or so. A recently released Gallup poll, for instance, found that church membership among Americans dipped below 50 percent for the first time on record – continuing a downward trend that started in the late 1990s. Between a quarter and a third of Americans now describe themselves as either atheist, agnostic, or nothing in particular, and a solid majority of these “nones” – some 57 percent in 2020 – call themselves Democrats. Indeed, half of the eight percent of Americans calling themselves “progressive activists” in a 2018 survey said they never prayed, compared with just 19 percent of all Americans.

In other words, many Americans no longer find organized religion particularly compelling as either a source of personal meaning or a way of life. Some of us have turned instead to philosophy to find meaning and establish structure in our lives, and it’s no coincidence that ancient Greek and Roman philosophies like Epicureanism and especially Stoicism have enjoyed something of a popular revival over the past decade or so. However, many others – and some progressive activists in particular – have looked to politics rather than religious or philosophical traditions provide them with a sense of personal meaning and belonging.

It’s important to note here that the human quest for personal meaning and a way of life does not necessarily require religion, frequent assertions to the contrary. Such claims are far too narrow in scope and unfairly stack the deck against secular and quasi-secular philosophies of life, from ancient Greek and Roman schools of thought to Taoism and some forms of Buddhism. They dismiss these worldviews in intellectually and sociologically unedifying ways, and don’t add much to our thinking about the subject at hand. Humanity may restlessly and relentlessly search for meaning and purpose, but it doesn’t follow that we all have a “god-shaped hole” that only traditional religion or its newly-minted substitutes can fill.

For many of its adherents, though, the new religion of progressive politics seemingly fulfills these vital functions and gives them a sense of meaning and purpose. In reality, however, this new religion gets things backwards: many believers derive their moral and ethical views from politics rather their moral and ethical commitments informing their politics. Viewing politics as a way of life and defining themselves by their political beliefs, they put far more weight on politics than it can possibly bear and invest it with far more significance that it can possibly give anyone. It’s a way of life that’s unmoored from the sort of moral and ethical commitments or wider worldview provided by philosophy or conventional religion – and helps explain the intolerance sometimes exhibited by the disciples of this new political faith.

The religion of progressive politics holds three articles of faith: anti-racism, climate apocalypticism, and gender identity. There’s no overriding rationale or underlying logic to this particular trinity of sacred beliefs, but they’ve coalesced over the past five or six years into nigh-unassailable dogma among progressive elites, activists, and funders. Other potential paths (like a brief flirtation with “democratic socialism”) were abandoned or forgone for seemingly arbitrary or accidental reasons, a process akin to the ways early Christianity resolved its down disputes as described by Diarmaid MacCulloch in his magisterial history of the religion. But a quick look at these three articles of faith makes it easier to see the religious nature at the hear of much of contemporary progressive politics.

Anti-racism. If there’s any one single belief at the heart of this new faith, it’s anti-racism: the notion of “whiteness” (or its equivalent “white supremacy”) as the mystical and all-pervasive source of evil in the world. As Musa al-Gharbi notes, there’s more than a whiff of gnosticism in the idea that believers “can see the ‘real’ structures of the world” while others remain blind to them. Likewise, the concept of “white privilege” stands in for the Christian doctrine of Original Sin, complete with ritual confessions of sin that can never fully absolve a person of their fallen state. It’s considered blasphemy or apostasy to disagree with these tenets in even the smallest degree, and those who do are treated as heretics. Anti-racism also has its high priests in the form of Robin DiAngelo and Ibram X. Kendi, authors of its two main sacred texts: White Fragility and How to be an Anti-Racist.

Climate apocalypticism. Climate change provides the new religion of progressive politics with a much more straightforward eschaton. Witness proclamations from progressives like Rep. Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez that we have about a decade to repent for our fossil fuel sins and avert the end of the world. In a similar fashion, well-intentioned journalists predict an “uninhabitable Earth” and a “sixth extinction” on the horizon. Teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg can quite reasonably be seen as the latest in a long line of child prophets. Viewing climate change through an apocalyptic lens, however, invariably moves it from the realm of practical politics and policy and into that of religious faith. It’s not hard to detect an apocalyptic streak coursing through Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal and similar proposals, with the unspoken notion that the specter of climate change will somehow force America (and indeed the world) to adopt progressive policy preferences across the board.

Gender identity. Finally, gender identity serves as the functional equivalent of the immortal soul for the religion of progressive politics, resting as it does an inherently subjective perception of one’s internal essence detached from the material reality of one’s own body. (As with anti-racism, it’s not difficult to discern more than a streak of gnosticism here – though it’s expressed in much more personal terms.) Disputes over this article of faith most often arise in the context of transgender issues, which rocketed to prominence among progressive activist groups after the Supreme Court legalized gay marriage in 2015. Those who question the notion of gender identity in any respect frequently find themselves accused of blasphemy or worse – just ask successful female authors like J.K. Rowling and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The American Civil Liberties Union of all organizations now calls for the censorship of books skeptical of the prevailing transgender ideology. Moreover, adherence to the sacred dogmas of gender identity leads some progressives into a denial of the science surrounding biological sex that would impress Young Earth creationists.

In the religion of progressive politics, assent to these three articles of faith marks an individual out as a good and moral person – and failure to actively affirm them marks one out as morally deficient and worthy of exclusion from the precincts of respectable society. Curiously, however, feminism and women’s rights failed to make the cut – a development all the more unusual in the wake of the #MeToo activism of recent years. Instead, women’s rights and feminism take a back seat to anti-racism and gender identity, with even the likes of Planned Parenthood flagellating itself for focusing “too narrowly” on its core mission of women’s health rather than trans rights or anti-racism.

It’s hard to deliberate on the nature of the common good and how best to advance it – something we dwell on here at The Liberal Patriot – when faced with the demands made by this new faith. When it takes on the the trappings of religion progressive politics risks calcifying into an unforgiving and inhumane set of dogmas. Presuming itself to be in sole possession of revealed truths about politics and society, the religion of progressive politics insists there’s a single correct way to think about the world and cannot tolerate even the slightest disagreement. It becomes impossible to accept that other people can, say, believe in racial equality or think that trans individuals deserve the same dignity and respect as every other human being without subscribing to the precise tenets of anti-racism or gender identity put forward by this new religion. Principled universalism of the kind we advocate at The Liberal Patriot presents a particular affront to these sacred beliefs and comes in for its own special form of opprobrium.

More than anything else, though, this mentality is a recipe for an intolerant and sectarian politics, one that shuts down debate and discussion rather than opening it up. It persists in part a due to the fresh and often still-open wounds of the Trump era, in particular the former president’s repeated dalliances with the far right and his failed attempt to overturn his 2020 election loss by instigating a violent insurrection on January 6. Four years of chronic exposure to the former president’s abusive stream of consciousness on social media alone would be enough to drive even the level-headed and logical Mr. Spock of the starship Enterprise out of his Vulcan mind - to say nothing of ordinary Americans subjected to these constant verbal assaults.

As those of us who disagree with this new religion and the intellectually debilitating shackles it imposes on politics and society do our best to remove these fetters, we should seek to foster calmer and healthier discussions about contentious issues – even just on a one-on-one basis. In large part, that means having enough confidence in our own ideas to speak openly and honestly about them in the face of pressure to conform to specific ways of thinking about politics and society prescribed by the religion of progressive politics.

While it’s much easier – not to mention simpler – for many of us to keep our heads down and try to get on with our work without raising a fuss, this understandable silence only encourages the worst of this new religion’s illiberal impulses. It fosters a false sense that there’s widespread support for these beliefs and impulses, when in reality there’s not much support for them at all - 80 percent of all Americans view “political correctness” as a problem, for instance, versus just 30 percent of those falling in the progressive activist category. Worse, it forgoes opportunities for persuasion and productive discussion with less zealous progressives and those with nagging qualms about the religious turn in progressive politics. It’s especially incumbent on those of us who see profound dangers in the religious transformation of progressive politics to practice what we ourselves preach when it comes to open discussion and respectful disagreement.

Above all, that means we need to stay grounded – not just in their own political beliefs in the equal rights and dignity of all Americans, but in our own philosophical and moral commitments that go well beyond and transcend politics. Indeed, there’s far more to life than politics, and it’s important to keep it in proper perspective even as we engage in it. We ought to see politics not as a way of life or a cosmic battle between supernatural forces of good and evil, but as a practical mechanism to organize collective action on behalf of the common good and secure the rights and dignity of all people.

That vision may seem pedestrian at first glance, but even the most pedestrian of visions can inspire.