Looking Beyond Tax Incentives

It's often cheaper and more effective for states to support policies like workforce training for businesses and targeted access to education over tax breaks.

Editor’s note: This is the fifth column in a TLP series on place-based policies by Upjohn Institute senior economist, Timothy Bartik. His earlier pieces focused on the basic rationale for place-based policies, examined the overall effectiveness of these approaches, explained why different cities and towns need different strategies, and showed why place-based policies are most needed in the most distressed regions.

Helping distressed places by getting more of their residents into good jobs has large social benefits, both in increasing earnings and ameliorating social problems. It’s worked in past programs such as the Tennessee Valley Authority. What works best will likely vary across distressed places, but what does the research evidence say on what types of policies tend to work best as a general rule?

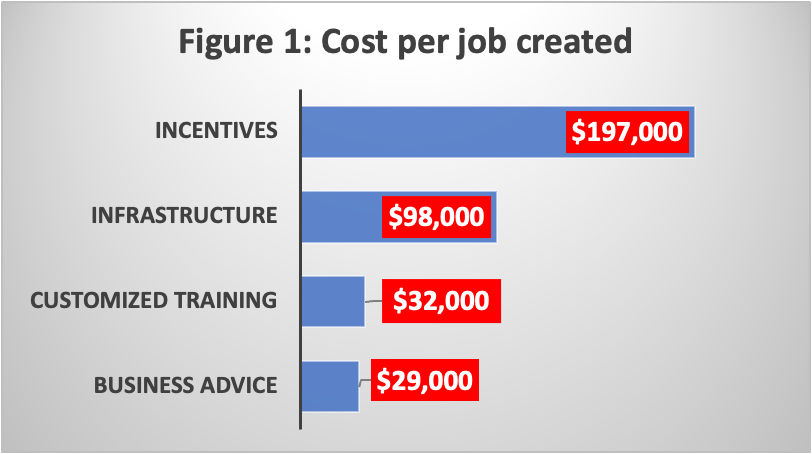

Business tax incentives can create jobs, but providing businesses with various services is often more cost-effective. As shown in Figure 1, infrastructure programs can create jobs at less than one-half the cost per job of business tax incentives. Customized job training programs, under which community colleges provide free job training to meet an individual business’s needs, can have even lower costs per job created at less than one-sixth of incentive costs. Similar low costs per job occur for business advice programs, such as manufacturing extension programs or small business development centers. Advice programs provide businesses with information on topics like adopting new technology, selling to new markets, or overall business plans.

Why is providing businesses with these “customized services” more cost-effective than simply handing out cash via business tax incentives? Simply put, these services are hard for many businesses to provide on their own. Well-run public agencies have some comparative advantages in delivering such public services. Some are cheap to provide—advice doesn’t cost much to deliver but can have enormous benefits if it’s good. High-quality land with the right infrastructure, skilled labor, and good business knowledge are basic requirements for economic development.

Public action to help provide these basics is more cost-effective in revitalizing a local economy than trying to overcome local problems with cash. Although handing out cash via tax incentives can induce some businesses to create jobs, the cost per job created is relatively high because many incentivized firms would still have made the same location decision, and hired many of the same workers, without the incentives.

Some caveats are in order: these business services are cost-effective in creating jobs only if they are high-quality; the proverbial bridge to nowhere is not cost-effective. Poorly-run training programs or manufacturing extension services will do little. Delivering high-quality business services can be challenging, while handing out cash is easy and can be readily scaled up.

Even though the roughly $200,000 per job created through business tax incentives comes at a high cost, job creation has enormous economic and social benefits in and of itself. More local jobs will increase local employment rates and will do so to a much greater extent in distressed local labor markets, where more people are available to hire. Local real wages (adjusted for local prices) will increase. Higher employment rates and real wages increase local earnings per capita, while social problems such as crime, substance abuse, and family separations decrease. These changes can be durable and long-term, as workers gain more job experience and further reduce the risk of social problems. The cumulative effect on earnings per capita alone can often exceed even a cost of $200,000 per created job. Business tax incentives can therefore still have local benefits greater than costs, and particularly so in distressed local labor markets.

But getting more residents into good jobs can also be accomplished by helping them gain greater access to existing good jobs—by increasing their skills, for example. High-quality education and skills programs often have higher benefit-cost ratios than incentives. As shown in Figure 2, incentives can pay off in distressed places, producing benefits (in the form of higher earnings) more than double their costs. But many programs that help residents gain skills or access good jobs can increase residents’ earnings by three, five, or even eight times these programs’ costs.

Why are there such large payoffs to programs that develop skills and improve job access? One reason is that in today’s economy there’s an enormous payoff to possessing credentials that allow access to good jobs. Additionally, when some workers upgrade their skills, there are spillover benefits on their coworkers. As its workers become more skilled in computer numerically controlled machines, for example, a manufacturing plant can introduce new lathes and other machinery that enhance the business’s competitiveness and thereby lift all its workers’ wages.

Some caveats again: these studies show the potential for high-quality training programs. A poorly run program teaching obsolete technology will not boost long-run earnings.

Moreover, many skills development programs pay off for different groups and on different timetables than do tax incentives and other economic development programs that immediately create jobs. For example, most of the higher earnings from investing more in childcare, pre-K, or public schools occur decades in the future, when former child participants are in their prime earnings years in their 40s and 50s. In contrast, economic development programs that create jobs today can elevate local earnings within a year or two, particularly for many middle-aged residents who might not want to go back to school.

Adult training and education programs may also have high returns, but only for targeted groups. For example, place-based college scholarships such as the Kalamazoo Promise can help many students by reducing financial barriers to college access, but students whose high school skills are weak may still struggle in college. Well-run training programs typically screen out many potential candidates who appear unlikely to succeed early on in order to ensure the program delivers quality trainees to employers. By contrast, earlier education programs tend to have benefits for broader groups, as children at earlier ages are more amenable to learning.

Finally, training and education programs can more effectively help residents access good jobs when these jobs are more plentiful. Job-creation programs by comparison have their highest returns when the local economy lacks sufficient good jobs.

So, which programs are the most effective in getting people into good jobs? Ideally, places should target both programs that work on the “labor demand side”—creating good jobs—as well as programs that work on the “labor supply side”—helping people earn credentials and skills needed to access good jobs. Labor demand and supply programs work better together; good jobs created can then be filled by a broad group of residents. The relative program mix should shift towards labor demand programs if the local labor market is weak, and towards labor supply programs if the local labor market is strong but some residents cannot access those jobs.

On both the demand and supply side, distressed places should emphasize the most cost-effective programs, and those programs should be sufficiently funded to deliver quality services at scale. Even if that’s accomplished, a role remains for targeting distressed places with selective business tax incentives to create jobs. Such a program responds to residents’ need for more good jobs in the here and now.

Furthermore, the services that make the most sense to add will depend on the local context. A local labor market with many small manufacturing businesses may benefit greatly from a manufacturing extension program, but more services-oriented local economies will not. Infrastructure and good industrial sites may be needed in some places but already plentiful in others. Local public schools and pre-K programs may desperately need higher funding in some areas but be in good shape elsewhere. Childcare may be readily available in some communities but absent in others, and so on.

As I have argued previously, flexible block grants targeted by federal or state governments to distressed places are among the best strategies to facilitate local economic development. These block grants, however, must be adequately funded. Few distressed places on their own can afford economic development spending of $300 per capita annually, the scale of the Tennessee Valley Authority at its height. Given the shortage of good jobs in distressed places, such a scale is needed for development aid to be adequate.

Even if distressed places choose cost-effective economic development programs, substantively addressing the lack of good jobs in these places cannot be achieved on the cheap. Cost-effectiveness is an important goal of place-based policies, but adequate scale is equally important.

Timothy J. Bartik is a senior economist at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, a non-profit and non-partisan research organization in Kalamazoo, Michigan. His research focuses on state and local economic development policies and local labor markets. At the Upjohn Institute, Dr. Bartik co-directs the Institute’s research initiative on place-based policies.