Amid ongoing battles between the Trump administration and various colleges and universities ostensibly over campus antisemitism, the new president of Yale University, Maurie McInnis, recently announced the convening of a “Committee on Trust in Higher Education.” Chuckles aside, the effort is laudable and more sector-wide self-examination and critical analysis from the elite bastions of higher education is warranted.

The Yale president laid out an ambitious if difficult goal for the new committee:

At this defining moment in higher education, it is imperative to understand the erosion of trust in colleges and universities nationwide. As they come under attack in the public square, universities must redouble commitments to academic freedom and free speech. At the same time, they cannot operate sealed off from the society in which they are embedded, and which they were established to serve. The future of American higher education depends on a restoration of public trust and legitimacy…

I will charge the committee to draw on the knowledge and experience of experts, citizens, and scholars—including members of the Yale faculty—to better understand public perception and envision ways of strengthening trust in higher education. The committee will engage the Yale community as well as its outside critics. It will invite external experts with varied viewpoints and backgrounds to provide perspective and to weigh how best to address the erosion of trust in higher education. It will explore possibilities for enhancing the open exchange of ideas on campus, in the classroom and beyond.

The committee and those more broadly interested in restoring public trust in higher education aren’t starting their inquiries blindly. The Lumina Foundation and Gallup have been tracking public attitudes towards colleges and universities for many years now and have presented some clear findings about the sharp decline in public confidence in higher education and the sources of this frustration, some of which are vaguely mentioned in the Yale letter.

The research involves multiple components including public tracking of attitudes toward higher education and specific surveys with existing students and those who have stopped their education or never enrolled.

Among the most important findings:

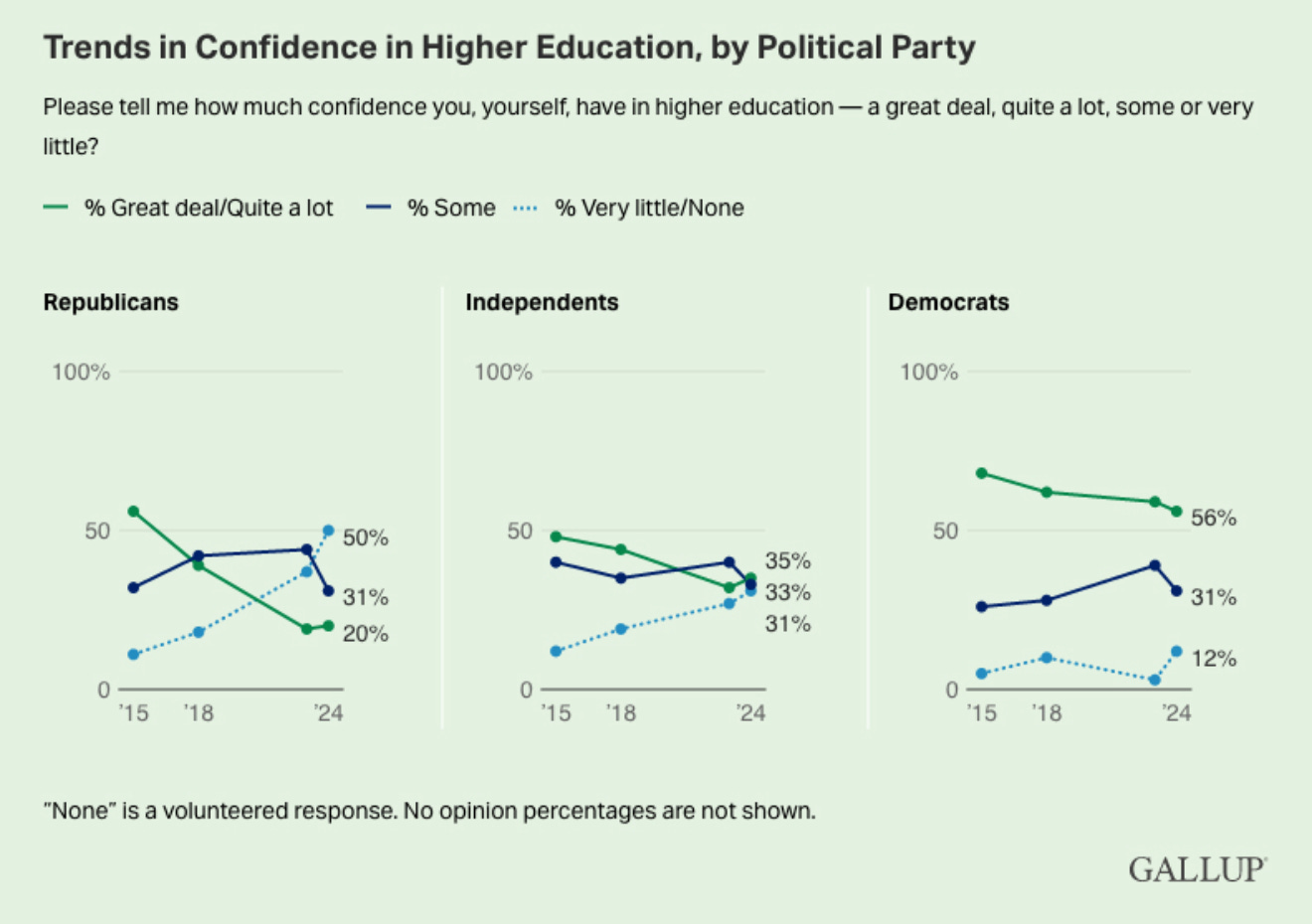

(1) Since 2015, the percentage of Americans who say they have a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education has dropped 21 points—from 57 percent to 36 percent in 2024. The percentage saying they have “very little” confidence or “no confidence at all” has climbed from ten percent to nearly one-third over this same period.

As with other indicators of institutional trust, a noticeable partisan divide has emerged to partially explain the decline in confidence in U.S. colleges and universities. Although trust has declined among nearly all demographic and partisan groups, self-identified Republicans have completely flipped in their sentiments towards higher education over the past decade. Consider that in 2015, 56 percent of Republicans held a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in higher education while only 11 percent held very little or no confidence. By 2024, only one-fifth of Republicans expressed confidence in higher education with half saying they had no confidence—a 75-point shift in the net confidence margin.

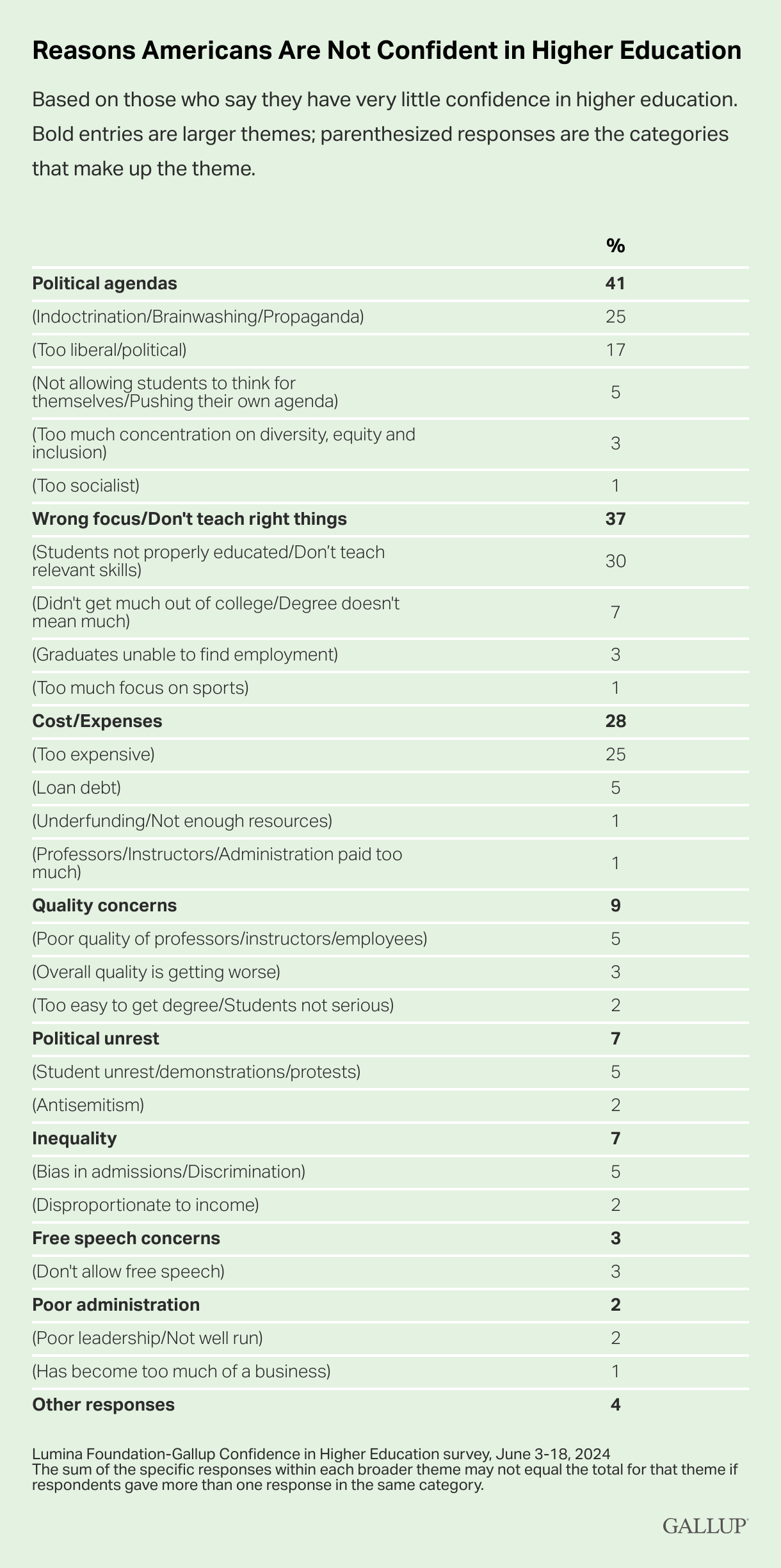

(2) There are three primary reasons for declining confidence in higher education—political agendas, colleges not teaching relevant skills, and cost. Gallup asked the roughly one-third of Americans who lack confidence in higher education to describe why they feel this way. Respondents were allowed to give multiple answers, and the responses were categorized into broader categories summarized in the table below. At the top of the list of concerns, more than four in ten respondents cited some aspect of perceived political agendas at work in colleges and universities—ideas including “indoctrination,” “brainwashing,” and “propaganda” or colleges being “too liberal” with “too much concentration on diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

Concerns about colleges and universities not fulfilling their core mission to educate young people and provide them with relevant information and skills necessary to succeed in the workplace nearly matched concerns about politicization on campus (37 percent combined). Likewise, a good chunk of Americans who distrust higher education cited high costs and debt as reasons for lacking confidence in these institutions (28 percent combined).

The partisan dimensions are again pertinent in understanding sentiments. As Gallup reported at the time: “A majority of Republicans who lack confidence in higher education, 53 percent, mention political agendas. Democrats who are not confident in higher education primarily cite the cost of it, while independents divide about equally between cost, political agendas, and misplaced teaching focus.”

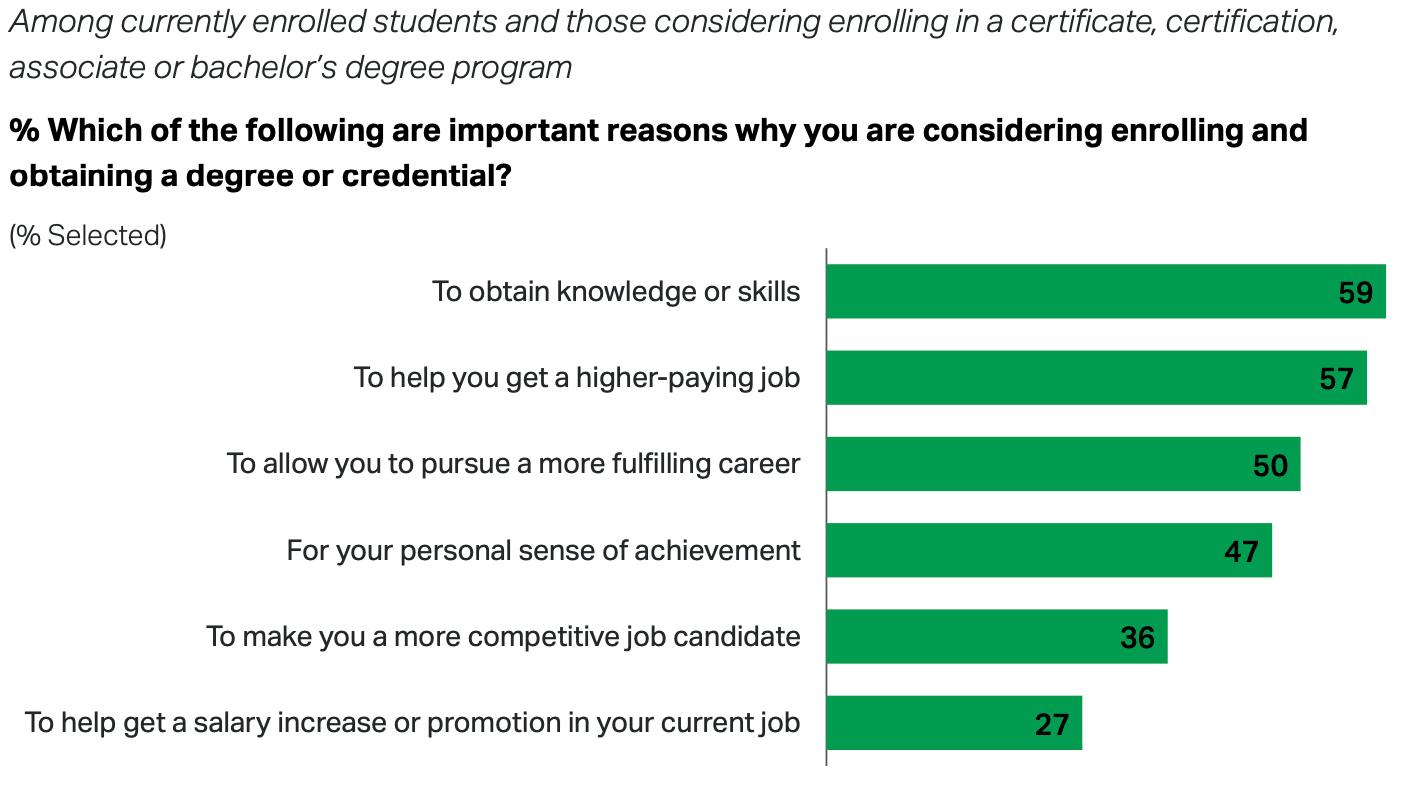

(3) Current and prospective higher education students are overwhelmingly focused on knowledge, skills, and employment when making decisions about school. As seen in the table below, nearly six in ten current and prospective students said that being able “to obtain knowledge or skills” (59 percent) or “to help get a higher-paying job” (57 percent) are important reasons for considering enrolling in a higher education program and obtaining a degree.

Likewise, among all current, former, and prospective students, the two most important reasons cited for staying in school or considering it are “confidence in the value of the degree or credential” and “financial aid or other scholarships you received.”

These practical job and cost concerns—along with other issues related to stress and mental health—are generally more important to students than the political ones cited by other Americans above. Notably, majorities of currently enrolled Republicans (61 percent), Democrats (64 percent), and independents (56 percent) agreed that their own institution “is a place where students can freely express all opinions on issues like politics.”

Public favorability towards higher education has been trending downward for a decade now. As the new Yale president and her colleagues examine the root causes of declining trust and confidence in their university (and others), regular Americans and students themselves seem clear about the reasons: Too many colleges and universities have become overpriced ideological playgrounds that are failing to impart vital knowledge and job skills to students.

People can do politics anywhere, and knowledge and skills can easily be acquired through other means. So colleges and universities looking to rebuild trust would be well advised to remain neutral and open-minded in terms of campus ideology and do much more to lower costs and make their degrees worthwhile for all students—regardless of their political and class backgrounds.

A fair assessment, but does not explore the role that faculty has played in creating this issue. Presidents of universities often have their hands tied by faculty who are driving a lot of these issues.

College tuition has increased at 3x the rate of inflation for the past 40 years as the ratio of administrators to students have skyrocketed.

Textbooks have increased at the same rate, despite the fact that technology has decreased the cost of the written word. Colleges blame new editions, but basic derivative calculus hasn't changed since Issac Newton.

Meanwhile, higher education is a negative-NPV financial transaction for most non-STEM majors.