Stop me if you’ve heard this before: Donald Trump wins the presidency, his approval rating quickly slides underwater, Democrats start cleaning up in special elections, and congressional Republicans are thrown into a panic about the upcoming midterms. Sound familiar? Yes, yes, yes, and yes.

Though our politics have changed dramatically since a certain golden escalator ride, the early months of Trump’s second term are starting to look awfully similar to those of his first term—at least electorally speaking. The hints have been there. A surprise flip in the Pennsylvania legislature. A narrower-than-expected Iowa state House race. But last Tuesday’s results in Wisconsin and Florida hammered home the message:

Democrats are dramatically overperforming in off-year and special elections—a trend that shows no signs of slowing.

In 2018, the end result was a blue wave and 41 new Democratic House members. Such is the million-dollar question looming over the second Trump presidency: will 2026 be a repeat of 2018?

Special elections have long been considered a solid political predictor. Individually they’re quite quirky, but collectively they usually point us in the right direction. Across 67 special elections in 2017, for example, Democrats outperformed Hillary Clinton’s 2016 margin by an average of 11.2 points. A year later, Democrats won the House popular vote by 8.6 points.

In 2022, even as hype around a red wave grew, special elections pointed to only a small Republican advantage. Across 28 special elections that year, Republicans beat Trump’s 2020 margin by an average of 2.5 points. Lo and behold, Republicans ended up winning the House popular vote by 2.7 points—just about matching their average special election overperformance.

Critics of the predictive value of special elections will point to 2024. Democrats were routinely beating Biden’s 2020 numbers throughout 2023 and 2024, before getting walloped when it counted most in November. They have a point: Democrats have a built-in advantage in low-turnout elections these days. Their college-educated base simply loves to vote, no matter the stakes. In 2026, some argue, Republicans will even the playing field when turnout rebounds. Perhaps the current Democratic advantage is merely a coalitional effect, just as we saw in 2024.

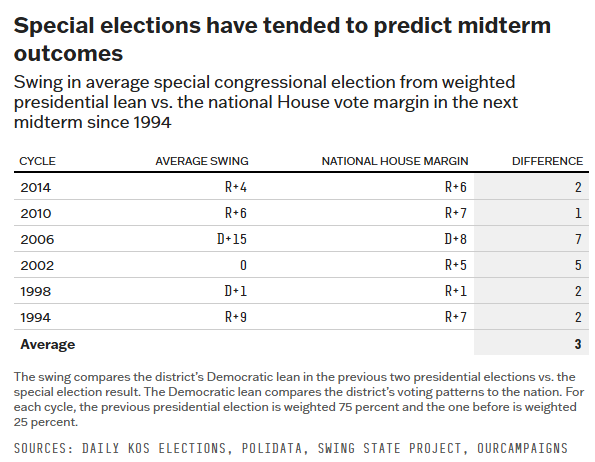

I’d argue, however, that while special elections may not be as valuable a tool in presidential years, they continue to be a solid metric in midterm years. Take a look at this chart from the 538 archives:

Again, not perfect, but a solid indicator of whether the party out of power is headed for a wave, ripple, or somewhere in between. Special election averages correctly forecasted big Republican years in 1994 and 2010, Democratic waves in 2006 and 2018, and, perhaps more impressively, the neutral-ish environments of 1998 and 2002.

Across 15 special elections in 2025, Democrats are outperforming Kamala Harris’s 2024 margin by an average of 10 points. Even if we assume a few points of that advantage disappears with traditional midterm turnout, early indications suggest a very blue environment in 2026. And then there are the elections that did not happen: Republicans yanked Elise Stefanik's UN nomination over fears of losing her Trump +21 seat. At first glance the decision seemed overly cautious. But in light of last week’s Florida results, where Democrats overperformed by 16 and 22 points in a pair of ruby-red congressional districts, the decision has aged well. Republicans very well could have lost Stefanik’s seat.

Though the overperformance was smaller than in Florida, the 10-point liberal victory in the Wisconsin Supreme Court race is arguably a better sign for Democrats. The contest was a decidedly nationalized election. Tens of millions in outside spending poured into the Badger State. National politicians endorsed and campaigned for the candidates. Elon Musk said the race “might decide the future of America and Western Civilization” (a slight exaggeration in this author’s opinion). Inundated with mailers and postcards, a Wisconsinite friend texted me after the election: “It was really out of hand. Worse than November.” In short, this was an election that felt more like a midterm than your average April off-year election.

Turnout backed up the hype. More than 2.3 million votes were cast, a 28.5 percent increase from the 2023 Wisconsin Supreme Court election. Republicans actually got the surge in low-propensity Trump voters they had been looking for: Brad Schimel, the conservative candidate, earned about 245,000 more votes than his conservative counterpart did two years ago. But liberals matched the increase—and then some. Susan Crawford received 1.3 million votes, nearly matching Mandela Barnes’ total from the 2022 Senate race. That’s welcome news for Democrats: Even as turnout pushed closer to midterm levels, the liberal candidate still won handily.

Of course, much can (and will) change between now and 2026. There’s still plenty of time for a Republican rebound. But, just as during Trump’s first term, early signs point to tough sledding for the GOP.

The Dems will do great in low turnout elections, and will lose the presidency and even more Senate seats in 2028. You offer working class voters nothing, and working class voters are the majority.

Elections are not a lottery. Can we get back to a real media discussing in depth real issues and answers to those issues? We know Democrats are against Trump. What are they for, please?