Iraq’s Future Will Be Shaped by the Next Generation

The challenge of building an inclusive nationalism is central to moving the country on a path towards progress.

America marked the twentieth anniversary of the Iraq war mostly by doing what it does best: engaging in self-absorbed debates with a mix of score-settling and catharsis, garnished with some ex post facto justifications of previously-held views about the war.

The 2003 Iraq war certainly did a lot of damage to the United States and its standing in the world—and it changed the lives of the Iraqi people in fundamental ways forever. Despite a handful of accounts in the U.S. media this past week that put the spotlight on ordinary Iraqis, coverage of the war’s anniversary has mostly passed with scant attention to the Iraqi people. For many years, Iraqis have been used as little more than props in America’s own domestic political and social disputes, with little attention paid to the full diversity of perspectives among Iraqis themselves.

Listening to what the people of Iraq think remains a vital part of understanding how the country might start to move beyond its troubled past and recent history.

Listening to Iraqis in 2003

In the summer of 2003, I spent several weeks in Iraq putting together one of the first public opinion research projects designed to actively listen to ordinary Iraqis and lift up their perspectives and concerns to a range of leaders. It was the first time I had extensive engagement with Iraqis of many walks of life.

When I studied in Jordan during the mid-1990s on a Fulbright scholarship, I met dozens of Iraqis exiled by dictator Saddam Hussein’s brutal repression. In cafes and on benches next to Roman ruins in the old part of Amman, Jordan’s capital, I came to know many Iraqis who packed up their families and left their homes behind to get away from both Saddam’s autocratic rule and awful economic conditions made worse by years of international sanctions and isolation. I also saw many talented Iraqi musicians perform classical and traditional Arabic music concerts around Amman. But it wasn’t until I traveled to Iraq in the summer of 2003 that I felt like I got a better sense of what life was like in the country.

Carrying out this research project brought me into the homes, schools, hospitals, and other community organizations where Iraqis gathered to share their views with a team of Iraqi researchers who worked with us to try and dig beneath the surface-level impressions. The research resulted in this first report produced for the National Democratic Institute, an American non-governmental organization, and the effort spawned and inspired other multiple qualitative research and polling projects that continue to this day.

Three key findings from this snapshot of Iraqi public views just months after the ouster of Saddam Hussein’s regime remain relevant to the challenge of building a stronger Iraqi society two decades later.

1. Good governance and basic security are the foundations for a stronger political economy and society.

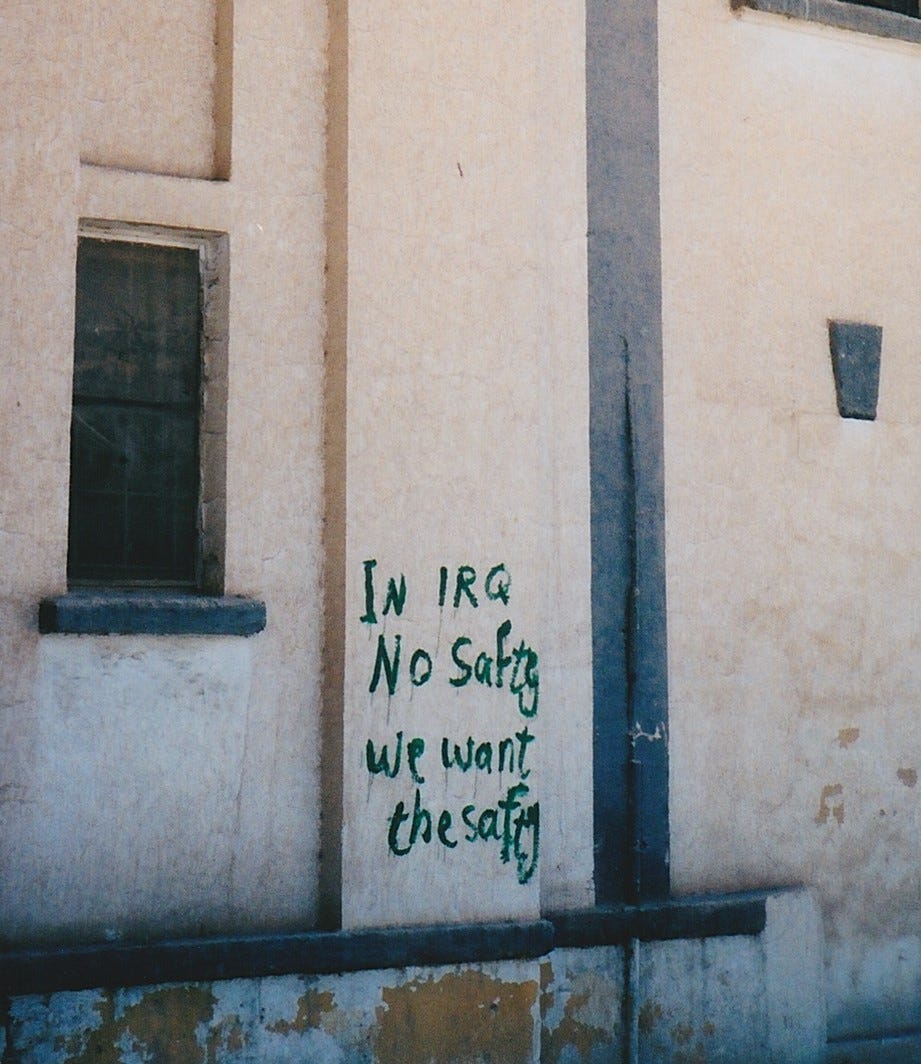

This research project was conducted before Iraq’s civil war broke out in full force, but ordinary Iraqis still saw a number of day-to-day challenges emerging thanks to multiple missteps by the U.S.-led occupation. First and foremost, the lawlessness that took hold in the aftermath of the invasion eroded trust within communities and created a shaky foundation for a new type of politics.

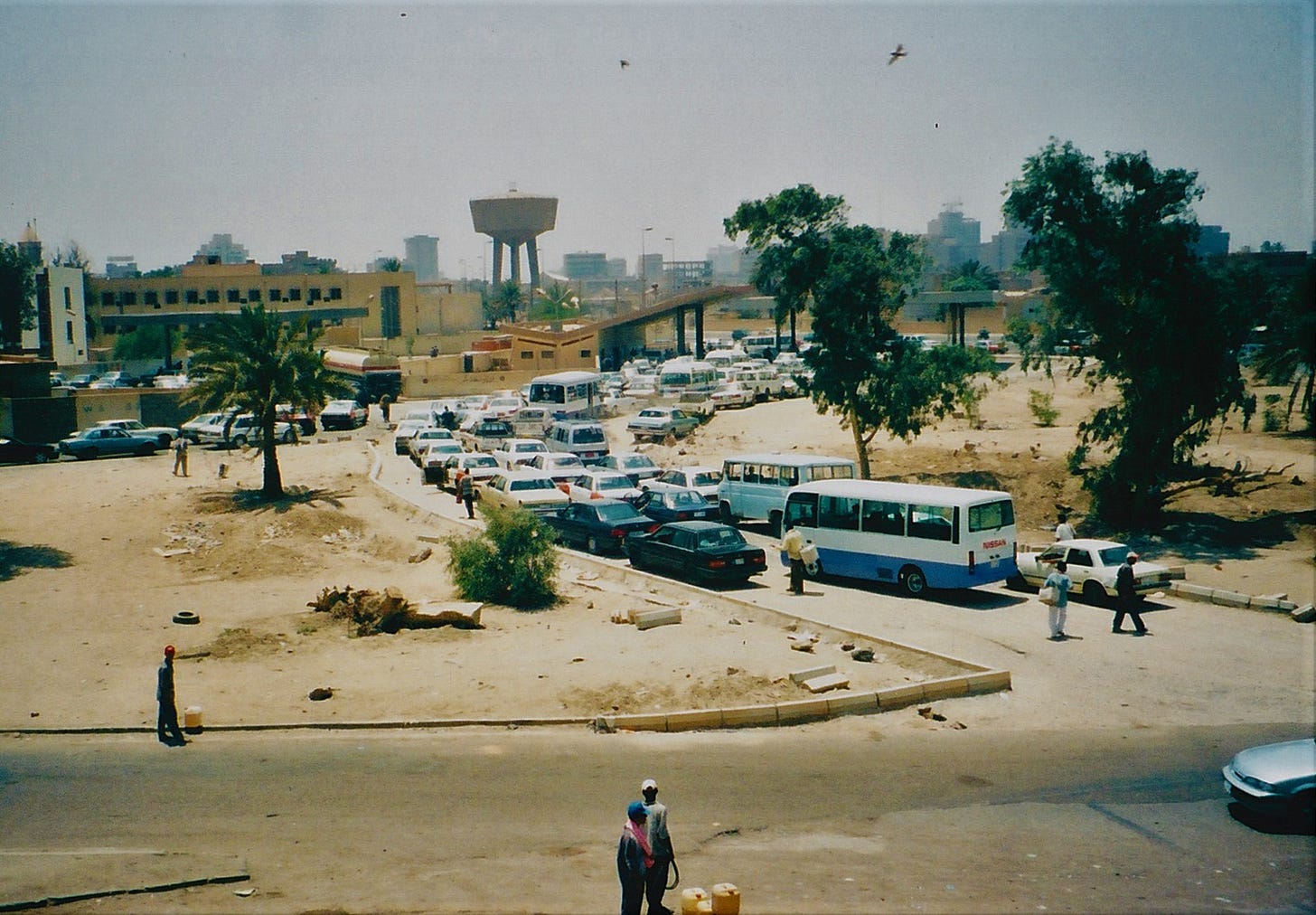

This growing insecurity added to the basic human security challenges faced by ordinary Iraqis. Iraq was and remains a major energy producer, but in the early months after the war started in 2003 the country suffered from regular electricity blackouts while drivers had to wait in long lines to fill up at gas stations.

The deteriorating security environment hurt Iraq’s economy and exacerbated its chronic structural difficulties, problems that resulted from decades of economic mismanagement and corruption exacerbated by international sanctions.

Interlinked challenges of growing public disorder, economic and energy crises, and lack of effective government set the stage for the broader meltdown that came in 2004—one that included a rise in terrorist attacks and the descent into multiple civil wars.

2. Foreign occupations often lack popular legitimacy and are hampered by a lack of connection with broader society.

In those early months after the invasion, our research project found that most Iraqis thought that the problems of growing insecurity, regular electricity blackouts, and gas shortages were part of a big plan to control and oppress Iraqi society rather than the result of incompetence and poor planning. Most Iraqis couldn’t imagine a military force that eliminated Saddam Hussein’s brutal regime in such a short period of time couldn’t keep the lights on, and there were many conspiracy theories that the disarray and confusion were part of a larger, more nefarious plan.

3. Iraqi nationalism remains a strong force binding society together.

Another important finding from this research project was that Iraqi nationalism writ large remained a strong part of people’s identity. When researchers asked respondents to choose from a list of words that describe them best—Iraqi, Arab or Kurd depending on the group, Muslim, a member of a particular family or tribe, and either Sunni, Shi’a, or Christian—the leading response was “Iraqi.”

Yet for a variety of reasons, perhaps driven by some influential Iraqis who had lived overseas for decades, many Americans and foreigners operating in Iraq used ethnic and sectarian identities as the main framework for engaging overall Iraqi society.

This sense of Iraqi nationalism remains strong today—particularly among the next generation of Iraqis. Cultivating a broader sense of inclusive Iraqi patriotism is an important element that could help the country move towards the future.

Listening to Iraqis in 2023

Perhaps too much has been written about the many steps and missteps on Iraq policy by the United States, and Iraq has gone through many ordeals to reach its present state. Iraq is a much different country today in 2023 than it was twenty years ago, in part because a whole new generation of Iraqis has come of age and looks poised to play a bigger role in their country’s future. Half of all Iraqis today aren’t old enough to have a living memory of what it was like to live under Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, leaving the country changed in large part because of the basic fact that time moves on.

Asking whether Iraq is better off now than before the 2003 war is an unfair question, argues journalist Mina Al-Oraibi in her excellent special podcast series looking at Iraq twenty years after the U.S.-led invasion. An Iraqi-Briton who is editor-in-chief of The National newspaper in the United Arab Emirates, Al-Oraibi points out that the war and its aftermath had a number of different effects on different parts of Iraqi society.

Her Iraq 20 Years On podcast provides an excellent starting point for this interested in learning about the full complexity of Iraq today precisely because Al-Oraibi gives voice to members of the country’s next generation. Mina Ali, a certified language trainer, talks about the mental health challenges she faces after being kidnapped as a young girl in the early years after Saddam Hussein’s removal from power. Ali Al-Saffar talks openly about the trauma he and his family faced after his father was kidnapped and disappeared in 2006. Individual and family scars add up after twenty years and impede Iraqi society’s ability to come together.

These young Iraqis describe their hopes for the future along with their concerns about chronic problems in Iraqi society. The country no longer experiences the levels of violence it once did, but widespread corruption and ineffective government remain significant issues. These problems have led young Iraqis to take to the streets in protests demanding reforms, and those reforms have been slow to come. Some want to give up and leave the country, while others want to keep up the fight in an environment of very imperfect freedom. Many are looking for a third way alternative that moves beyond the status quo politics, to build something that helps unify Iraqis around a new sense of positive nationalism.

The sense of Iraqi nationalism and a strong Iraqi identity remains strong years after the initial public opinion research conducted just after the 2003 war. In this 2021 poll, a majority of respondents in Iraq responded that they consider themselves “Iraqi above all” other identities, including various sectarian and ethnic identities. Over the past few years, younger Iraqis took to the streets in massive protests starting in 2019 against widespread corruption, poor governance, and unemployment. “No to muhasasa,” the word for the sectarianism that has dominated Iraq’s politics for decades, was a prime message of these protestors. There are glimmers of hope that political coalitions can be built across sectarian and ethnic lines in a new inclusive Iraqi nationalism, but these hopes have not yet been fulfilled.

When the United States started the Iraq war twenty years ago, few predicted the massive costs it would have for our country or the impact it would have on Iraqi society. It is hard to foresee what Iraq will look like in 2043, but that future will be determined not only by the country’s present-day political leaders but those young Iraqis who are calling for and seeking something new.