How to End the War in Ukraine by Defeating Putin

Why America and its NATO allies need a clear play to stop Putin here and now - not the fantasies of realists and "restraint" advocates

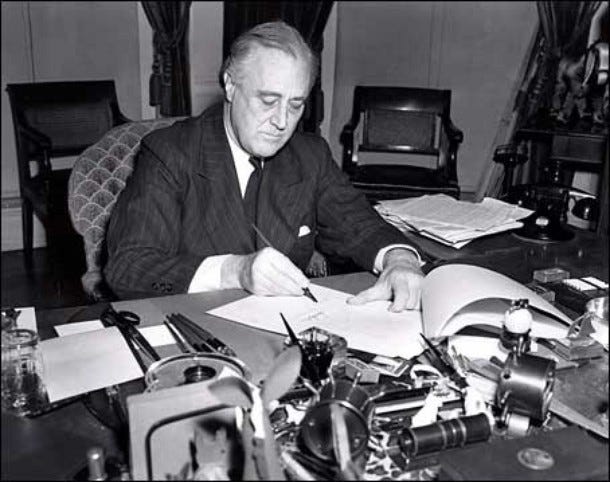

“Give us the tools,” Winston Churchill proclaimed as Congress debated President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Lend-Lease proposal in February 1941, “and we will finish the job.”

When Lend-Lease passed the following month, President Roosevelt promised that Britain and its allies fighting the Nazis would “get tanks and guns and ammunition and supplies of all kinds.” Though the United States would eventually be drawn into the war, American military aid to the Allies proved indispensable to the ultimate victory over Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. “If the United States had not helped us,” Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev recalled in his memoirs, “we would not have won the war.”

Today, the United States and its NATO allies ought to make a similar commitment to Ukraine. With its initial military thrust toward Kyiv defeated, Moscow looks set to escalate the war in Ukraine’s east. While initial emergency shipments of anti-tank and short-range anti-aircraft missiles helped Ukrainians defend their capital and blunt the initial Russian offensive, the next phase of the war will likely require military assistance from the United States and its allies above and beyond what has already been provided – and what they’ve been willing to provide thus far.

The stakes remain higher than they’ve been for decades: for all its flaws as a democracy, Ukraine now occupies the frontline of the free world’s belated stand against bullying dictators like Vladimir Putin. It’s far better for the United States and its allies to stop Putin now, in Ukraine, in part to reduce the risk of a larger war between NATO and a sullen, belligerent Russia in the future. Supplying Ukraine with the weapons it needs to fend off renewed Russian offensives also represents the best way to support negotiations that could lead to a real peace agreement – not an inherently unstable and temporary truce imposed on Ukraine by the Kremlin.

By providing Ukraine the military tools it needs to win its war against Russia, the United States and its allies ultimately advance their own values and protect their own interests.

What would a new, twenty-first century Lend-Lease program for Ukraine look like, then?

1. Recognize that Ukraine is part of a wider struggle and plan accordingly. Above all, it would not be limited to Ukraine. Too many NATO allies have under-invested in defense over the years and decades since the end of the Cold War, and claims from some allies like Germany that they cannot afford to both meet their alliance commitments and supply the Ukrainian military cannot be dismissed. Other nations on the alliance’s eastern flank have drawn down their own weapons stockpiles to help Ukraine, and some like Slovakia have requested modern replacements for the Soviet-era systems they’re willing to forward to Ukraine. Any modern Lend-Lease program would need to have two main prongs: one directed toward supplying Ukraine with the necessary weapons to beat the Russian military, the other toward rearming NATO members and hardening the alliance’s eastern flank.

2. Expand efforts to help Ukraine defend itself and defeat Russia. Along with continuing the flow of anti-tank missiles, portable surface-to-air missile systems, kamikaze drones, and light armored vehicles already under way, the immediate priority should be to supply Ukraine with heavy weapons like T-72 tanks and MiG-29 fighter jets that will require minimal training time and learning for Ukrainian soldiers. This Soviet-era hardware can be drawn from the stockpiles of NATO allies, as we’ve already seen in the case of Slovakian S-300 surface-to-air missiles and Czech T-72 tanks. Poland has made it known that its fleet of MiG-29s is available to Ukraine, as has Slovakia.

Here, it will be important for the United States and its NATO allies to stop deterring themselves and wringing their hands about perceptions that such arms transfers will be seen as “escalatory.” Putin and his inner circle already believe they’re at war with the United States in Ukraine, and refusing to supply Ukraine with the weapons needed to counter a Russian attack in their country’s east will not make the Kremlin reconsider this fundamental attitude. The risk that proactive measures to support Ukraine’s military short of direct U.S. and NATO intervention will trigger some sort of Russian escalation remains minimal and therefore acceptable.

Over the longer term, the United States and its NATO allies should begin training and equipping Ukraine on American and European systems. As National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan noted, the next phase of the war in Ukraine “may very well be protracted” – among other things, meaning that Ukrainian soldiers and pilots should have the time to become familiar with new weapons systems. Newly-excess F-16, F/A-18, and Gripen fighters could be potential options here, and the German defense giant Rheinmetall has said it could send fifty surplus Leopard 1 tanks to Ukraine over three months once given approval by the German government. There are a number of options available, and the United States and its allies should pick one as soon as possible to begin training Ukrainian soldiers and pilots. It’s an effort that will require “creativity and pragmatism,” as German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock put it.

The purpose of providing this equipment would be to help Ukraine win its war against Russia and reclaim its sovereignty. A victory on the battlefield would allow Kyiv to negotiate with the Kremlin from a position of relative strength and end the war on terms take Ukraine’s legitimate security concerns into full account. It’s also the best way to keep any peace that results from negotiations; a peace that includes a Ukraine capable of standing up to Kremlin aggression is more likely to be observed over the long haul.

3. Reinforce NATO’s eastern flank. Here the top priority should be to replenish the stockpiles of NATO members that have provided Ukraine with weapons since the start of the year. Likewise, a modern Lend-Lease program should seek to replace the Soviet-era equipment still used by a number of eastern flank NATO allies. These tanks, surface-to-air missiles, and fighters can be provided to Ukraine, but the capabilities they provide to NATO will need to be replaced by modern American and European hardware. Indeed, a number of these allies already have replacement fighters and tanks on order, and the United States should expedite the delivery of this new equipment to the extent possible.

That’s particularly important given the threat faced by frontline NATO members like Poland, Romania, and the Baltic states. As Brian Katulis has pointed out, these countries - and Lithuania in particular - constitute a key front in the global struggle for freedom. As unlikely as a Russian attack on these allies may seem given the Kremlin’s military troubles in Ukraine and Putin’s general wariness of direct confrontation with NATO and the United States, these countries have good reason to worry about Moscow’s future intentions. Indeed, senior Putin regime officials like Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov have made clear they do not see these nations as sovereign and independent.

Active American assistance should also be on offer to other NATO allies in search of replacements for their stocks of aging Soviet-era hardware. The quick supply of surplus F-16s, for instance, could help bridge the gap for a number of eastern flank allies as they await delivery of orders for new versions of the fighter. Whatever form or shape it may take, the purpose of this Lend-Lease prong would be to strengthen and harden NATO’s eastern flank even as many members divest themselves of equipment to help Ukraine. If Putin’s attempt to establish an imperial sphere of influence is not stopped in Ukraine, the alliance may well face the ultimate test of its commitment to collective defense.

To make this program work, Congress would need to pass legislation. The Senate has already passed its own version of Lend-Lease for Ukraine, and the House should take up the measure as soon as practicable. President Biden should appoint a trusted advisor to run this new iteration of Lend-Lease, in much the same way that President Roosevelt put political confidant Harry Hopkins in charge of administering the original effort. He should also invoke the Defense Production Act when needed to restock supplies of weapons like Javelin anti-tank missiles and accelerate the production of new hardware for NATO allies.

It's difficult to say how much a new Lend-Lease might cost; recently signed arms deals with NATO eastern flank nations Poland, Bulgaria, and Slovakia for new American Abrams tanks and F-16 fighters amounted to less than $10 billion. It should therefore not be prohibitively expensive to mount an effort to supply Ukraine with the weapons it needs, mainly from surplus U.S. and NATO stocks, and provide new equipment for NATO allies – especially those geographically closest to Russia. That’s a small price to pay to help Ukraine defeat Putin’s military and create the conditions necessary for serious but difficult diplomacy to begin.

It's time for the United States and its allies to live up to their ideals and protect their interests by giving Ukraine the tools it needs to finish the fight against Russian aggression.