How the Liberal Order Strikes a Balance

Political theorists from Thomas Hobbes to John Locke to James Madison understood that if human beings didn’t have government, they would need to create it. At its best, government forges order out of chaos, providing security and allowing for development. How we choose to create that order as a nation determines what kind of national government we get.

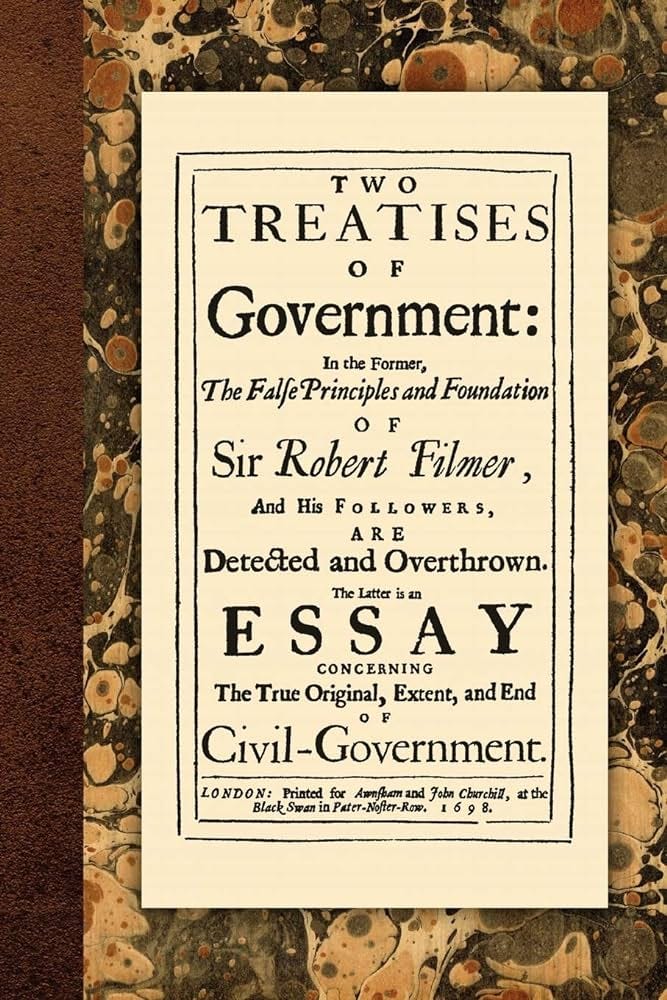

Hobbes wanted absolute monarchy while Locke and Madison instead argued for limited government that protects individual rights while allowing for common action. For more than 230 years, our country has relied on the liberal order of Locke and Madison to strike a balance between liberty and tyranny, freedom and order.

In the last decade, however, public policy failures on a host of issues have demonstrated that Americans are no longer resolved in their commitment to the values of the liberal order that Madison used to craft the Constitution to produce a properly functioning government. More recently, America’s policy disagreements have developed into deep-seated hostility towards one another in ways that threaten the social order that the Constitution has provided.

If we are to find a way back to a more constructive democracy, we must begin with a reexamination of what beliefs we can agree on and take necessary steps to reform the political system to help uphold them.

In general, humanity has tried to create rules that enable us to live together. When we all comply with those rules, or are forced to comply, things generally go smoothly. When we choose not to comply with the rules because we don’t agree with them—and the government is either unwilling or unable to force us to comply—our society fails and chaos reigns.

Without order lives are at risk. Without order, economic activity becomes challenging at best—and dangerous or even impossible at worst. And while government exists to create order, the question of what kind of order is left open to be determined.

In our liberal order in the United States, we usually emphasize “liberal.” However, liberal is just an adjective—albeit an important one—that modifies the noun “order”, and if the emphasis shifts to order it becomes more apparent that order exists in contrast to its absence: disorder, or more colorfully chaos and anarchy. We don’t need to agree with Hobbes’ underlying claim that anarchy is humanity’s “state of nature” to see what’s happening in front of our eyes every day in the United States: increases in violent crime, anti-social behavior, and homelessness, as well as open drug abuse plaguing many of our great cities and towns.

But as classical liberalism demands, our desire for order must be balanced with firm protections of personal liberty. Classical liberals, whatever their other political or policy views, all believe that legitimate political authority derives from the individual. A government of the people, by the people, and for the people rests on a belief in the sovereignty of an individual, particularly over his or her own body and own conscience. It is from that belief that all our freedoms emerge, and it is from this sovereignty that the American people can grant the “consent of the governed” expressed in the Declaration of Independence and implied in the Constitution.

Today, that foundation of liberalism is lost amidst more popular perceptions of what it means. That has left Americans without a lack of sure footing in several policy debates—unable to properly balance personal liberty and the need for order.

Let’s consider two specific areas where the liberal order is failing.

The Second Amendment and Gun Violence

Lost amidst partisan and ideological battles over gun rights, we have failed to recognize and protect an individual’s basic sovereignty over their own body. Americans have a basic constitutional right to bear arms to defend that sovereignty if necessary. They also have a right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness uninterrupted by gun violence.

However, in our society today, the sheer number of guns and the likelihood of them being used improperly clearly exceeds the government’s ability to protect individuals from bodily harm.

This was clear just this past 4th of July, which saw a number of mass shootings in the United States and the consequential infringement on the rights of others to pursue their own lives free from harm by others. When gun violence happens on such a wide scale—and as a society we can’t find a proper balance between individual rights and public safety—we are left either with the option of everyone with a gun, which would truly be akin to Hobbes’ state of nature, or to embrace a police state that confiscates everyone’s weapons through more authoritarianism.

Neither of these solutions make sense but we currently lack the ability to find a middle path out that protects people’s rights on all fronts—the right of Americans to own a gun and the right of all people to be safe and free from harm.

Mass Migration and Border Controls

The immigration debate is another contemporary example of this tension between individual rights and order. International law, and our own domestic laws, have long recognized the sovereignty of individual immigrants and their right to seek asylum from wars and natural disasters or political, ethnic, religious, and other abuses. But in order to properly function, and control our domestic borders, the government must preserve the right of an immigrant to enter the country through legal channels and to be returned in a speedy and just manner if it is determined that their claim to residency (or asylum) is too weak to allow it.

When the government fails to agree on these core principles of individual rights and national borders, then the state is also unable to agree to funding and judicial proceedings sufficient to handle immigration claims in a managed, expeditious, and legal manner. As such, the state finds it impossible to accept applications for residency in a fair and just manner, and we’re left with the equally unpalatable options of opening the gates wide open (which is chaos) or shutting them entirely (which is reactionary). Neither of these options are liberal—or American—in the classical and historical sense.

As with guns, our political system appears incapable of finding the proper balance on immigration. So we are stuck shifting back and forth between strategies, bending laws and rules, leaving people in limbo, and not adequately controlling our borders.

The Founders understood this kind of tension between unfettered liberty and order very well and were quite worried that the American Revolution would set in place a series of events that would lead to constant whiplash between the two. The liberal order that they created is designed to try to help balance those tensions through a system of checks both on the individual and on government, and through a commitment to value pluralism and rational compromise between divergent interest groups and parties.

Sadly though, as these two issues demonstrate, the liberal order is failing. The questions are why and what we do about it.

The why is simple to answer. First, we self-select our political tribes today in a way that undermines our collective ability to tackle complex problems such as gun violence or illegal immigration by encouraging partisan stand-offs rather than compromise. This hyper-polarization, that for the purposes of elections manifests geographically, has resulted in a lack of competition that undermines American pluralism and the cooperation among competing interests necessary to address tough challenges. At such a point that one faction begins to believe that concessions are unnecessary, the liberal order loses its value to that faction.

In a healthy pluralist system, our Constitution is designed to make it difficult to get things done without compromise. However, in an illiberal environment, it becomes nearly impossible to get things done without authoritarianism. This frustrates ideologues further, leading to even more focus on consolidating power to achieve desired objectives.

Meanwhile, we face frequent policy stalemates on many important issues facing the country, lurch from threatened government shut down to threatened shut down, and most importantly, undercut public confidence in the government.

What to do about it is a much more challenging question.

For starters, we need to create more opportunities in our voting process for pluralism to grow. Our current first-past-the-post electoral system completely discourages weaker candidates from being taken seriously by the electorate. We’ve all seen this play out, particularly in congressional districts that rarely change sides. Our presidential elections also leave people wanting more than one of the two options they are offered.

In established democracies around the world, there are an array of ways to choose winners that can mitigate this problem. Many of those systems are quite complicated and shifting to them would probably raise far too much confusion and resistance in the United States because Americans think our system is so simple and straightforward—which in many ways it is.

However, we could do something on a national level that 21 states have already done in some form: implement run-off processes or ranked choice voting. In the first model, minor party candidates have a stronger chance to compete because they don’t have to get 50.01 percent of the vote to win, but merely need to come in second. In the latter, voters can select second and third choices so that if their preferred candidate doesn’t get a minimum percentage of the vote, their second choice or their third choice gets their vote. A more radical option, at least for electing members of the House, could be to abandon congressional districts all together. The Constitution does not require them, and there are several other ways states could select from their candidates to produce better representation and encourage pluralism.

These reforms can be left up to the state legislatures, as some have done, or they can be taken up by Congress per the Constitution. The political will to pursue them is entirely another matter. Any practical reforms will depend on having a debate about the deeper philosophical question of how as a country we want to avoid chaos.

Creating an effective national government while constraining it in favor of individual liberty was how the Founders chose to balance the tensions between unfettered liberty and tyranny. It’s worked pretty well for almost two and a half centuries, and we should find ways to reinforce and reinvigorate it going forward.

David Nassar has spent 30 years working to strengthen democracy and pluralism in the United States and around the world.