How Much Will Abortion Influence the 2024 Presidential Race?

The issue has undoubtedly helped Democrats, but it may not be enough next year.

Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in its June 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson ruling, American politics has experienced a seismic shift—one that has without question benefited the Democratic Party. Voters in deep-red Kansas resoundingly defeated a ballot measure that would have opened the door to a statewide abortion ban. Democrats began routinely overperforming their baselines in special U.S. House elections, which had previously generated more mixed results. Then, they defied history in a relatively successful midterm after putting an almost singular emphasis on abortion. This year, liberals notched a big win in Wisconsin’s high-profile state Supreme Court race, which centered heavily on the issue.

Many political observers have interpreted these results as the consequence of GOP overreach—the threat to abortion rights from extremist legislators has awakened a sleeping giant in the electorate, the argument goes, and voters are turning out in full force to defend these rights. Post-election surveys have found that threats to abortion access motivated key groups of voters—in particular, independent women—to back Democrats. And it is absolutely true that many Republican candidates and elected officials find themselves on the wrong side of public opinion with this issue.

Given all this, some have come to believe that so long as Republicans continue pushing for restrictive laws around the procedure, Democrats will have the upper hand in elections for the foreseeable future—including in next year’s presidential election. Democrats certainly seem to agree, with recent reports indicating they are trying to get pro-choice measures on the ballot to energize their voters and put Republicans on the defensive.

But it’s worth asking just how much we can and should extrapolate from the results of these aforementioned contests as we look ahead to an election in 2024 that will have much higher turnout and bring with it a different electorate.

Here are a few observations to keep in mind:

Lower-turnout elections produce different electorates

It’s a political truism that lower-turnout elections produce fundamentally different electorates than higher-turnout elections. Special and primary elections, for instance, tend to attract more highly engaged, often college-educated voters—a demographic that has leaned toward Democrats in recent years. So, it wasn’t surprising when, in a higher-turnout election like a midterm that brought out voters who sat out these lower-turnout affairs, Democrats’ overperformances in these places came back down to earth.

Take Kansas: an 18-point rout for the pro-choice ballot measure option in last August’s primary election did not translate to a rout for pro-choice Democratic Governor Laura Kelly, who won re-election in the November midterms by just 2.2 points. The primary not only disproportionately attracted voters who cared about abortion rights but also took place in a vacuum. The governor’s race was much more competitive in large part because many of the counties that supported the pro-choice option saw a lower increase in relative turnout from the primary to the general than the counties that supported banning abortion—in other words, the midterm electorate was less liberal overall than the primary electorate.

Another example comes in Nebraska’s First District, which historically has leaned fairly Republican. The GOP won the post-Dobbs special election here by just 6.4 points. However, they won the higher-turnout midterm election by more than twice that margin (15.8 points) when more conservative-leaning voters showed up.1

These examples and others show it’s worth exercising some caution when interpreting the results of the midterms and the Wisconsin Supreme Court race—both of which seemed to hinge on abortion—as it relates to the 2024 presidential election. Indeed, the results of the last two midterm elections held before an incumbent president ran for re-election were not at all indicative of how the country would vote two years later. Similarly, the results of Wisconsin’s state Supreme Court contests in 2011 and 2019 were not harbingers of how the state would vote for president the following years.

In sum, the 2024 electorate will look very different from those that have powered Democrats to stronger-than-normal performances since Dobbs, making it unwise to conclude too much from these recent results.

Support for choice doesn’t always mean support for Democrats

Even as the threat to abortion rights has energized much of the Democratic base, there’s a meaningful segment of voters who support protecting a woman’s right to choose but who will also vote Republican. According to the AP VoteCast survey of 2022 midterm voters, nearly a third of all voters who said abortion should be legal in all or most cases voted Republican in their U.S. House race. The survey also showed that those who said they “somewhat favor” a law “guaranteeing access to legal abortion nationwide” broke for Republicans by 13 points, 55–42 percent. Perhaps an even clearer way to think about this is that the same electorate that supported making abortion legal in all or most cases by an almost two-to-one margin supported Republicans in the national U.S. House vote by nearly three points.

This reality was also evident in the five states where abortion rights were literally on the ballot in 2022: California, Kentucky, Michigan, Montana, and Vermont. The electorates in all five backed the pro-choice option on their respective ballot measures, and yet this did not uniformly translate to greater support for Democrats. Across these states, Democratic candidates underperformed the “pro-choice/defend abortion rights” option by an average of about 11.4 points.

The two most vivid examples of this disparity came in Kentucky and Montana, both historically Republican states. Even as electorates in each state voted down new restrictions on abortion, Republicans—many of whom are openly hostile to abortion rights—won contests up and down the ballot and sent veto-proof Republican majorities to their state legislatures. In Kentucky, where AP VoteCast survey data was available, Republican Senator Rand Paul won roughly 40 percent of voters who said they favored a national law guaranteeing access to legal abortion and who believed abortion should be legal in all or most cases. He even won a majority of voters who supported abortion exceptions for rape, incest, and the life of the mother. Meanwhile, in Montana, turnout was down 7.1 points compared to four years ago, constituting the 10th-greatest drop-off of any state—even as the chance to defend abortion rights was on the ballot.

In deep-blue California and Vermont, moreover, the presence of pro-choice ballot measures did not necessarily lead to dominant showings for Democrats. Turnout in the California governor’s race was down 12 percentage points from 2018 to 2022, and the state swung 5.4 points rightward. Things were slightly better in Vermont, where turnout was actually up 1.1 points from the high-turnout 2018 midterms and Democrats retained longtime U.S. Senator Pat Leahy’s seat and the state’s lone U.S. House seat by wide, if smaller, margins. But incumbent Republican Governor Phil Scott, a moderate on abortion issues, secured another term over a Democratic challenger by his widest margin yet.

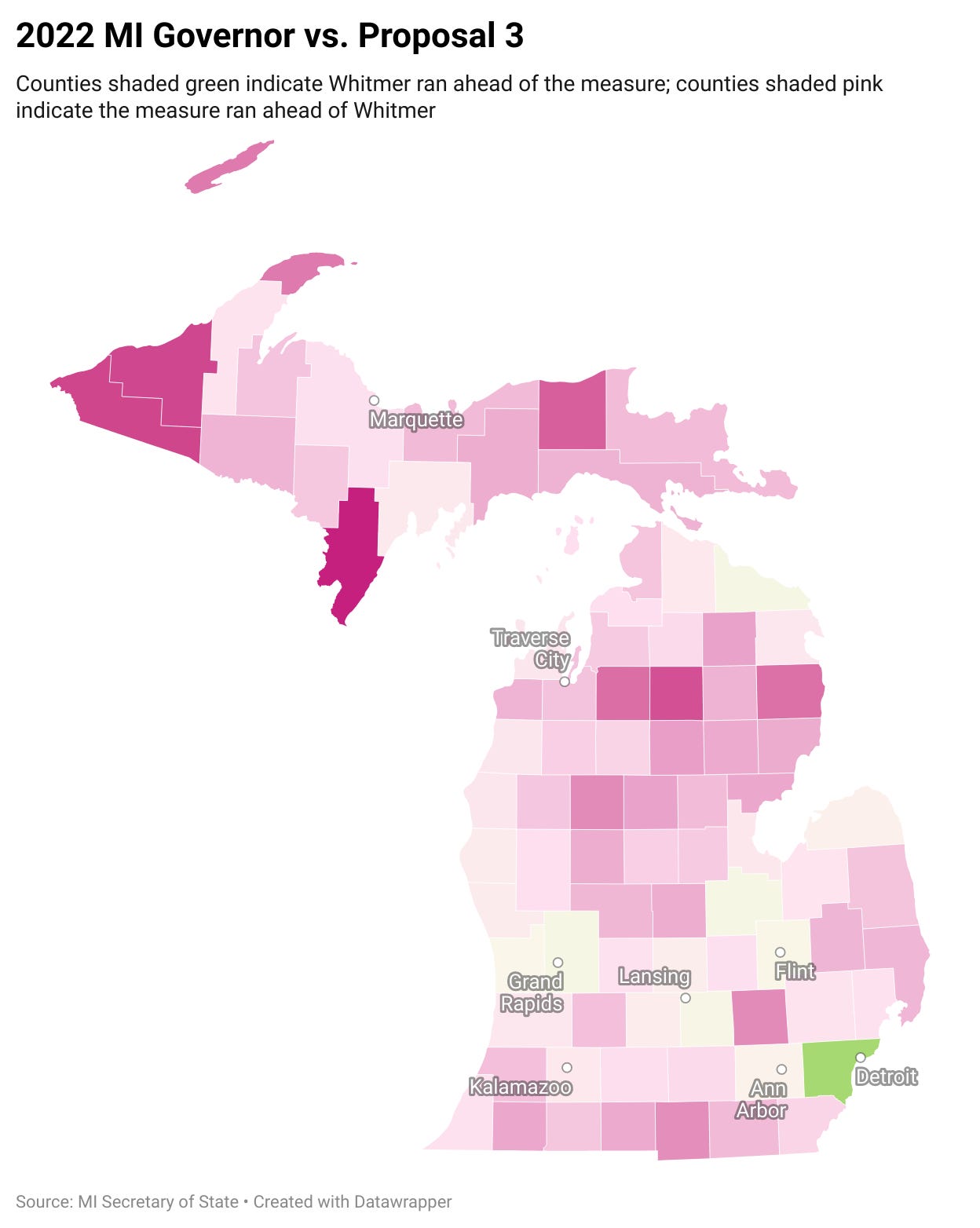

Perhaps the clearest example of where the abortion issue may have helped Democrats is in Michigan. All three of the state’s top Democratic officials—Governor Gretchen Whitmer, Attorney General Dana Nessel, and Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson—won re-election by slightly wider margins than they enjoyed in the 2018 blue wave midterm. And indeed, some of the best-educated counties in the state, like Washtenaw (Ann Arbor), Oakland (suburban Detroit), and Leelanau (North Michigan), swung left by the largest margins, consistent with the idea abortion especially motivated college-educated voters. It was clear that voters were jazzed about voting in Michigan, too: turnout was up by five points from the high-turnout 2018 midterms.

Even here, though, the story is a little complicated. Part of the reason turnout may have been up from 2018 is simply that Michigan had multiple competitive statewide contests, unlike in the other four states. Of the 61 counties whose turnout relative to 2018 was higher than the statewide average, 53 broke for Republican gubernatorial candidate Tudor Dixon. Moreover, the ballot measure enshrining abortion rights into the state constitution outran Whitmer in 76 of the state’s 83 counties, and eight counties voted for the measure while backing Whitmer’s Republican opponent.

In short: while Americans are fairly supportive of abortion access and largely oppose onerous restrictions on the procedure (and encroachments on their personal rights more broadly), it does not follow that all voters who hold this view will turn around and vote for the party that mostly shares it.

Lessons from Wisconsin

The latest electoral contest from which political observers are drawing lessons is the state Supreme Court contest that took place in Wisconsin earlier this month. Liberal candidate Janet Protasiewicz trounced conservative opponent Daniel Kelly, and many have pointed to her support for abortion rights as the core reason why.

To be sure, abortion played a central role in the race. But there are several reasons why the issue’s salience this year does not necessarily portend obvious trouble for Republicans here next year. First, Protasiewicz’s margin of victory (55.5–45.5 percent, or 11.0 points) almost exactly mirrored 2020 liberal candidate Jill Karofsky’s margin (55.3–44.7 percent, or 10.6 points) over the same opponent. At minimum, these facts should force analysts to question whether threats to abortion were singularly responsible for Protasiewicz’s win or if there might have been some other contributing factor, such as Kelly’s general weaknesses as a candidate (more on this in a moment).

Second, Wisconsin has been a perennial presidential battleground for decades—over the past 50 years, just two candidates, Bill Clinton in 1996 and Barack Obama in 2008, have carried it by more than 10 points, and only three have won with more than 50% of the vote. Even when polling has shown candidates way ahead during the campaign, they often come back down to earth. The average margin between the winner and the loser during that time has been a meager 2.3 points, and there is no reason to presume Protasiewicz’s wide margin of victory this year will change that reality with a very different electorate next year.

Finally, in the same election, voters across the state overwhelmingly backed three conservative-leaning policies that were on the ballot, including two related to stricter cash bail rules and one expressing support for work requirements for those receiving welfare from the state. All three measures received at least two-thirds support, and a majority of voters in every county backed each one. If nothing else, it’s a reminder that many voters have views that cut across ideological lines, and that makes them unpredictable: just because a voter supports abortion access doesn’t mean they are liberal or will vote Democratic all the time.

Still, Protasiewicz’s win offers Democrats some useful insights into how they can effectively leverage abortion to their benefit. In a recent recap of the campaign with Politico, some of Protasiewicz’s top aides discussed how anger over abortion alone wasn’t enough to win—the issue had to be tied to a broader narrative about GOP extremism, and even then, the context of the issue in Wisconsin, specifically, mattered:

Four top aides to Justice-elect Janet Protasiewicz’s campaign — campaign manager Alejandro Verdin, general consultant Patrick Guarasci, media consultant Ben Nuckels and top spokesperson Sam Roecker — said that running on abortion doesn’t work without tying it to a larger message. They argued that the candidates’ own values matter when making abortion an issue. So too do the legislation or laws at stake.

“We were careful to create a narrative early on about who Janet was, what was at stake in this election and who Dan Kelly was, and abortion fit within that,” Guarasci said. “Our paid media ends with ‘he’s an extremist that doesn’t care about us.’ Everything related back to that.”

In other words, abortion was one example of how Protasiewicz’s opponent was too extreme. Moreover, because the result of this race would have a significant impact on the future of abortion laws in the state, her campaign was able to rally liberal voters and tip enough swing voters for whom the reality of the threat was now obvious. Even so, a majority of the ads Protasiewicz’s campaign ran were not about abortion but crime—an acknowledgement that while Democrats may have an advantage on the abortion issue, Republicans have their advantages too.

Overall, Democrats have found success in their three Blue Wall states in part because Republicans have nominated candidates whose views on abortion fall way outside the mainstream. Yet, some GOP governors who signed strict abortion laws managed to successfully fashion themselves as moderates and secured re-election in 2022, signaling that while abortion may work to the advantage of Democratic candidates under the right circumstances, they should not view the issue as a silver bullet.

Why these considerations matter

It’s entirely possible that threats to abortion rights will persist into next year, and the top two GOP presidential contenders seem bent on providing Biden and Democrats ammunition to make that argument. Last week, former President Trump, who had been mostly mum on the issue since Dobbs, defended his administration’s efforts to restrict access to abortion in front of a crowd at the Iowa Faith and Freedom Coalition. For his part, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis recently signed a six-week ban into law—a measure voters overwhelmingly oppose nationally and in his own state. Biden has taken notice and prominently featured a defense of abortion rights in his re-election announcement video.

Still, it’s unwise to assume we know what the top issues facing the country will be by next fall—or to expect that abortion will be among them. Heading into the fall 2021 elections, the topics consuming our national political dialogue included the botched withdrawal from Afghanistan, the ongoing fight against COVID-19, and critical race theory in public schools. By the time the midterms rolled around in 2022, those issues barely registered for most voters or candidates.

No one knows what we’ll be thinking and talking about a year from now. It’s possible the seeming urgency of the abortion issue will have faded—polling suggests that voters consider other issues more pressing at this point. While many Democrats still seem content to simply coast on abortion, it’s likely they’ll need to tell a story that goes beyond just this issue if they want to win in 2024.

Unfortunately, the other three post-Dobbs special elections—MN-01, NY-19, and NY-23—were held under the previous decade’s maps, so an apples-to-apples comparison with the midterm results (held under this decade’s maps) is impossible. But we do know that 25 of the 27 counties that existed fully within those three districts under both maps swung rightward from the special elections to the midterm election.