How Issue Consensus Turns to Dust

Agreement on a common agenda drops off as soon as partisan cues get tripped.

Partisan polarization has been fingered as the cause of any number of problems in contemporary politics from the rise of divided government and ideological extremism to beliefs in conspiracy theories and the spread of misinformation. A less examined aspect of how partisan sectarianism degrades democracy involves the role of party cues in turning issue agreement among Americans into issue warfare.

This isn’t simply an instance of Democrats and Republicans disagreeing on an issue, and looking for points among base voters, so nothing gets done. Rather, it’s more that Americans themselves often agree on many issues but then this consensus blows apart once political elites on both sides indicate that “it’s not our issue” or that someone they hate likes this issue so our side can’t agree to it anymore.

Primary examples of this trend in recent decades involve health care and immigration.

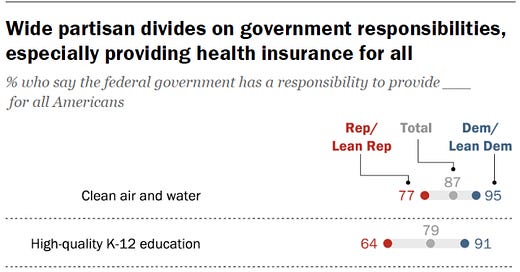

If you look at the most recent Pew data, majorities of Americans across party lines believe the federal government has a responsibility to provide clean air and water and high quality K-12 education. Beyond these two issues, however, partisan splits are pronounced—particularly on the issue of the government provided health insurance. As seen in the chart below, there is a 55-point gap between Democrats and Republicans on whether the government has a responsibility to provide health insurance.

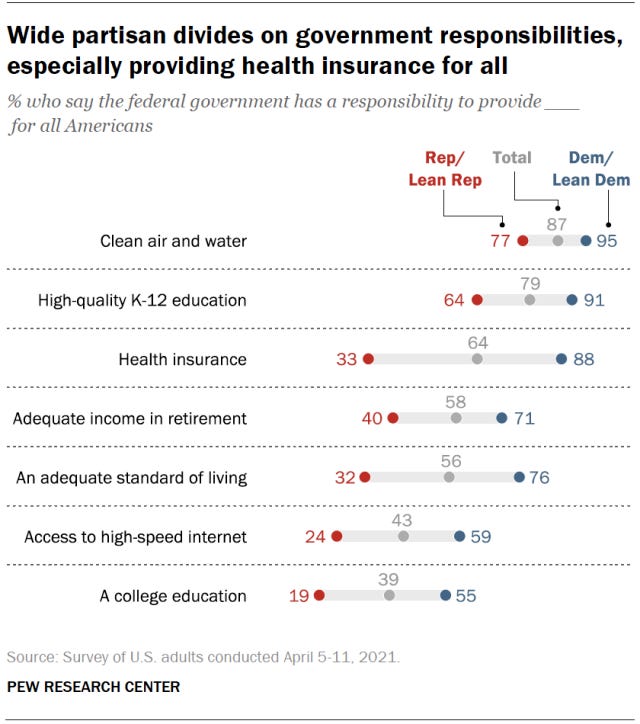

Republican voters haven’t always been opposed to government doing more to provide health insurance. Looking at Kaiser time series data, as recently as 2006 nearly three quarters of Republicans favored the government doing more to provide health insurance. By 2019, however, that figure had dropped to 40 percent among Republicans, while dropping only slightly among Independents and staying virtually unchanged among Democrats.

What happened in the interim? Debate and passage of “Obamacare” and the push among some Democrats for an even more ambitious national health plan such as Medicare-for-All. What was a relatively common goal of expanding health insurance to more people in the second term of George W. Bush’s tenure turned into a scorched-earth battle by the middle of Trump’s presidency, with little sign of abatement today.

Do Republicans not want health care for themselves? No, of course not. They just emphatically despise Democratic models for extending access to health insurance to more people. Meanwhile, Democrats probably care about health care more than any other issue and support far-reaching government proposals for universal coverage.

Since more people agree with Democrats on health care than they do Republicans, the Obamacare status quo holds for now as the two sides dig in on their respective positions without any meaningful chance of constructive action to improve health care provision and services for Americans.

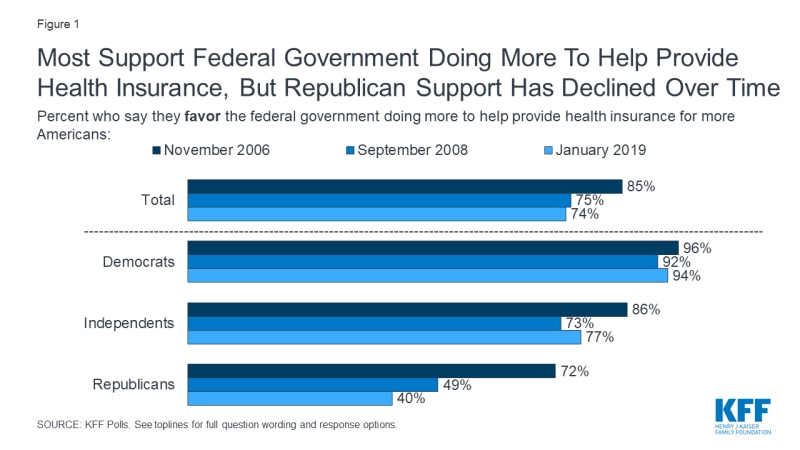

The same polarization emerged over the past two decades on the issue of immigration. As a 538 analysis shows, Democratic and Republican opinions on immigration were much more aligned in the early 2000s when President Bush’s “compassionate conservatism” structured public debate on the issue. But then things dramatically shifted:

While there were still some concerns among Democrats about the impact of immigration on the American worker, the pro-union wing of the party became more pro-immigrant after mounting pressure from other unions, in particular service-worker unions, many of whose members are Hispanic. The AFL-CIO also reversed its anti-immigrant positions, calling in 2000 for undocumented immigrants to be granted citizenship. Another major development during the latter part of this decade was an omnibus immigration reform bill Republicans pushed through Congress in 2006, which didn’t become law, but would have emphasized border security and raised penalties for illegal immigration.

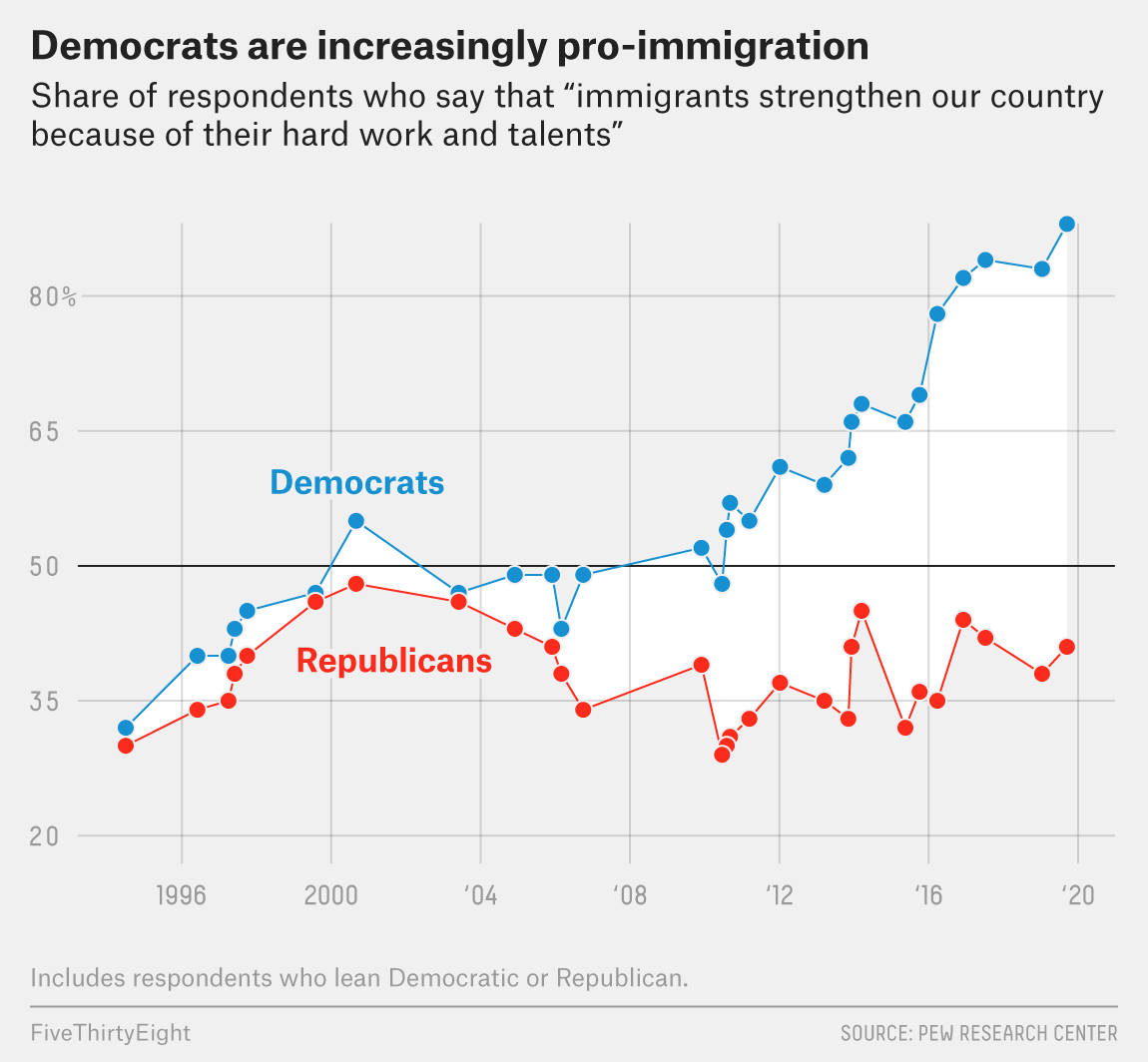

This is also when Republican and Democratic voters began to dramatically split on immigration, according to polling from the Pew Research Center. In the mid-2000s, the two parties were pretty close in their views. When asked in 2003 if immigrants make the country stronger, 47 percent of Democrats and people who lean Democratic and 46 percent of Republicans and people who lean Republican agreed. Now, though, nearly 90 percent of Democrats feel that way compared to just 40 percent of Republicans.

Although Ronald Reagan once opposed putting up a fence along the Mexican border and supported amnesty, and George W. Bush spoke earnestly about immigrants contributing positively to American life, many conservatives disagreed with party elites. Likewise, Democrats in the late 1990’s favored more managed inflows of immigration and expressed concerns that “illegal immigration was rampant”, but then moved steadily away from this posture towards a more open borders position.

Politicians on both sides subsequently changed their tunes to more adequately reflect their voters’ will and to make immigration less of a negotiable matter. Donald Trump eventually rode opposition to immigration all the way to the presidency, which in turn further pushed most Democrats into staunchly pro-immigrant positions culminating in some fairly radical proposals in 2020 including the decriminalization of border crossings.

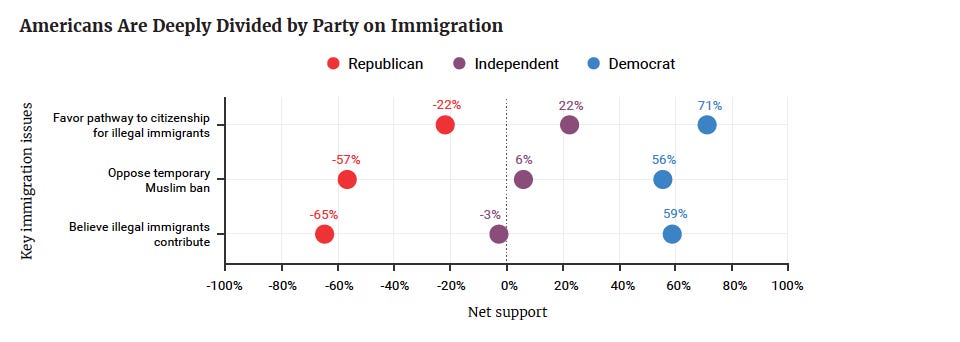

Today, as Patrick Ruffini shows, the two parties have diametrically opposed views on all aspects of the immigration issue. For example, Democrats by a 71-point margin favor a pathway to citizenship for illegal immigrants while Republicans by a 22-point margin oppose this idea. Likewise, Democrats by 56-point margin oppose a temporary ban on Muslim immigrants while Republicans support the idea by an almost identical 57-point margin.

Partisan cues were developed and triggered on both sides of the immigration debate, and so any possibility for consensus outside of some protections for immigrant children has evaporated.

As the country tries to get back on its feet after the coronavirus health and economic crises, Americans are anxious about the state of the country and their own financial position. Consequently, polls show that voters support a range of measures to create new jobs, to help American businesses compete better with China, and to strength workers and families facing economic insecurity. It’s important for the country to get some of these ideas in place and not to fall into the same patterns that have disrupted consensus building and progress on health care and immigration.

The Biden administration cannot and should not try to control the public debate entirely. But it can do its best to promote consensus policy ideas in ways that don’t structure the issues in strictly partisan or ideological terms.

So make recovery, public investments, and job creation for everyone—and for the country as a whole—to help break the cycle of partisan-induced stasis on ideas for improving our national economy. Focus on reducing inequalities in all regions of the country, and for all groups of people.

This approach may not work given the hardened nature of partisan politics today. But it’s worth a try to begin bridging some of the divides in society and hopefully produce tangible economic benefits for more Americans.