Do Place-Based Policies Work?

Helping residents of distressed places with “place-based policies”—such as creating good jobs in those places—is an admirable goal. But can it be achieved?

My first column argued that bringing jobs to distressed places could help both the residents of those places, and the nation. But such help will not be forthcoming if it is simply too difficult to bring jobs to distressed places. By definition, distressed places have economic problems, and a skeptic might say that maybe most of these problems are not readily fixable.

But considerable empirical evidence exists that even cash incentives—like business tax incentives or cash grants for business job creation—can have benefits greater than their cost in distressed local labor markets. Even if cash incentives are expensive per job created, job creation in distressed places has social benefits that are extremely large—and job creation in such places can raise the employment rate for many years by giving local residents more skills from experience and reducing the likelihood of substance abuse and crime. Ten or more years of full-time employment in a good job—not holding a job off and on—adds up to hundreds of thousands of dollars in economic and social gains for each extra job created.

Such large benefits can be created more cheaply through various customized services to businesses as well. For example, good business advice—such as that provided to smaller manufacturers via manufacturing extension services—is relatively cheap to provide. But it can greatly affect job creation by helping manufacturers sell to new markets.

It’s more intuitive however, to point to specific places that have succeeded, despite many challenges, as a result of place-based policies. Five historical examples stand out:

(1) The Tennessee Valley Authority—1933 to present, with peak activity from 1940 to 1960. The TVA, an important component of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, provided a multi-state Southern region, with about 5 million total population at the time, with assistance in rural electrification as well as help with public health, job training, and industrial recruitment. Research comparing the TVA region with similar regions suggests that the TVA created about 250,000 permanent manufacturing jobs in the region.

(2) The Appalachian Regional Commission—1965 to present, with peak activity in late 1960s and early 1970s. The ARC targeted a high-poverty region consisting of 13 states with about 20 million residents in the mid-1960s. Two-thirds of ARC funds went to improved highways, and research shows that ARC highways increased employment in affected counties by around 5 percent and per capita incomes by 1 percent—which adds up to many multiples of highway construction costs.

(3) Lehigh Valley Pennsylvania—1980s to present. After the steel industry collapse of the early 1980s, the Lehigh Valley area was able to rebound by diversifying to manufacturing beyond steel and developing other industries like warehousing and high-tech industries. Policies to promote this recovery included the development of seven industrial parks, state funding for a high-tech partnership that includes a business incubator and research grants to encourage spinoffs from Lehigh University, as well as brownfield development initiatives. Despite national manufacturing job losses over the last 15 years, manufacturing in the Lehigh Valley has grown.

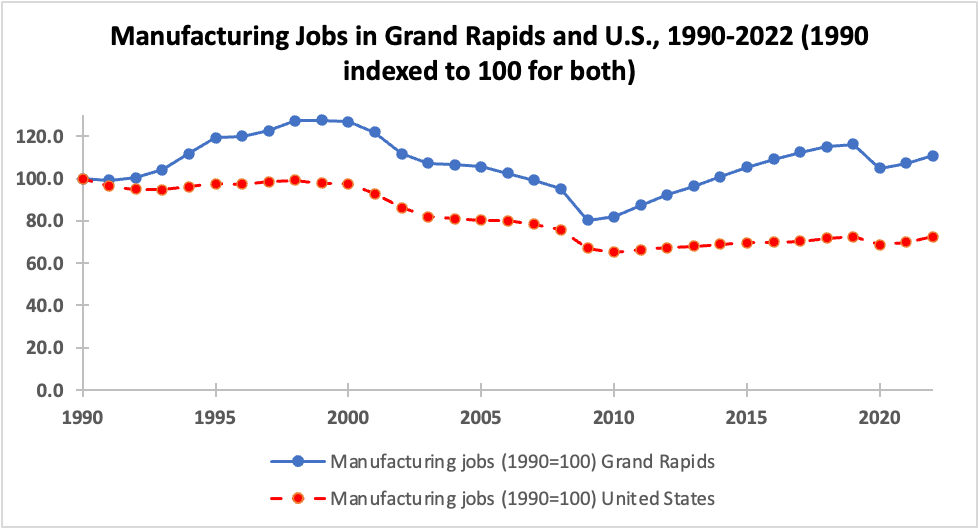

(4) Grand Rapids, Michigan—1990 to present. Arguably the most successful manufacturing-intensive city in the United States, Grand Rapids saw its manufacturing employment grow by over 10 percent from 1990 to the present—all at a time that U.S. manufacturing jobs shrank by over a quarter. This success may be due in part to tax incentives, but the Grand Rapids area also convened industry clusters to advise on job training improvements, invested in health care research, encouraged continued local ownership of family firms, and advised smaller manufacturers on moving into other markets. As one example, a firm that made auto parts was able to find new markets in making orthopedic products.

(5) Crosby/Ironton, Minnesota—2011 to present. A small community of less than 3,000 people on the southwest edge of Minnesota’s Iron Range, the Crosby/Ironton area’s open pit iron mines have been closed for over 30 years and have since become lakes. But in the past 15 years, state funds have been put into mountain biking trails around these lakes, making the area more attractive for biking competitions. Tourism has doubled, leading to new restaurants, brewpubs, and other local businesses.

These diverse examples reinforce a central tenet of helping distressed places: one size does not fit all. In each example, public policy built on area strengths and addressed some area weaknesses—lack of electrification in the TVA region, poor highway access in the ARC area, the need for more business parks and incubators in the Lehigh Valley, the over-dependence of Grand Rapids on the auto industry, and the need for new infrastructure to better capitalize on natural amenities for Crosby/Ironton.

The lesson, in other words, is not that every distressed rural area should build mountain biking trails or that rural American communities in today’s economy need “electrification”. Policies must be tailored to the needs of each distressed area and community, playing to its strengths and weaknesses in order to make appropriate and effective public investments where they can do the most good.

Some currently distressed rural areas possess sufficient natural amenities to attract remote workers, retirees, and some employers if rural broadband is upgraded, for instance. But this strategy may make less sense in less amenity-rich rural areas. Some local economies have local universities (such as Lehigh University) to help boost high-tech via business incubators and research spin-offs, but other local economies do not have such local higher education assets to make such a strategy viable. Likewise, a wide variety of locally owned manufacturers may still exist in some local economies such as in Grand Rapids, and with the right job training assistance and advice on finding new markets these local manufacturers can be made competitive. A strategy focused on manufacturing may make less sense, however, in formerly manufacturing-intensive local economies that have lost most of their small manufacturing businesses.

Funding such strategies is not cheap. Most local governments in distressed areas lack sufficient tax bases to fully pay for the needed investments in infrastructure, real estate, job training, and business advice programs to help rebuild their communities. Moreover, it’s probably true that some distressed local labor markets have such large economic challenges that it will be difficult to turn them around and create sufficient jobs. But many other distressed places have the potential for successful revival with sufficient help from state and federal governments as well as from private contributions.

To give distressed places a chance, we should help these places develop reasonable economic strategies that play to their strengths—not impose cookie-cutter approaches on vastly different areas. If such a strategy can be developed—and there is no reason to believe it cannot be—then both federal and state governments should fund it at sufficient scale to help turn around distressed communities and improve local job prospects. Even if success is never guaranteed, bringing jobs to people and places that need them has large enough benefits that it justifies significant investments.

Timothy J. Bartik is a senior economist at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, a non-profit and non-partisan research organization in Kalamazoo, Michigan. His research focuses on state and local economic development policies and local labor markets. At the Upjohn Institute, Dr. Bartik co-directs the Institute’s research initiative on place-based policies.