Democrats Win a Status-Quo Election

But pundits should be wary of extrapolating too much from the results.

On Tuesday, voters in several states went to the ballot box to make their voices heard in the final set of elections before presidential primary voting begins next January. The focus of these elections varied widely from state to state, but it was overall a good night for the Democrats. In Virginia, they retained control of the state Senate and flipped the state House of Delegates by narrow margins in both. They made even further inroads in the already heavily Democratic New Jersey legislature. Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear won a second term—and by a wider margin than before. Voters in Ohio overwhelmingly supported ballot measures protecting the right to an abortion and legalizing marijuana. And the party’s state Supreme Court candidate in Pennsylvania won an important race with big implications for 2024 and beyond.1

While these results carry a real-world impact and undoubtedly came as great news to many in the party, they also run up against new polling showing President Biden sinking further with the electorate and in a dead heat with former President Trump heading into 2024. Many political observers have been trying to make sense of this seeming contradiction as best as they can—how is it that the president’s party continues to find electoral success even as he is as unpopular as ever? There are some clues about this and much more to take away from this week’s results.

1. This was a status quo election, which mostly benefited Democrats.

More than anything else, voters made it clear that they did not want to rock the boat in this election. Indeed, in almost all of the high-profile races, the status quo won. Both incumbent governors on the ballot were re-elected—and in Kentucky, Republicans retained control of several other statewide executive offices. Democrats kept (and slightly expanded) their big majorities in both chambers of the New Jersey Legislature. In Ohio, voters resoundingly rejected an effort by Republicans in the state to impose further restrictions on their reproductive rights, which would have constituted a major change to life in the state. Even in Virginia, where Democrats narrowly flipped the House, the state will continue to experience divided government, as Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin enters the second half of his term next year.

2. Democrats’ Virginia wins obscure some problems under the surface.

While Democrats had a good night overall in Virginia, this was likely due in no small part to a friendlier map than the one used in 2021. The party’s candidates found some success in districts that leaned their way, but it got tougher in more competitive territory. Of the four Senate seats and seven House seats considered “toss-ups,” Democrats only won one and three of them, respectively. They also failed to win any “lean Republican” seats in either chamber. Perhaps even more alarming: Republicans won nine districts that backed President Biden in 2020, including one (HD-82) that broke for him by 10.7 points.

These results track with the state’s politics since 2020. In 2021, when Republicans flipped the governorship and state House, 12 districts swung from Biden to Youngkin (including the nine Biden seats that Republicans won this year). However, it doesn’t appear that 2021 was necessarily a fluke. Of those 12 districts, only six swung back to Democrats in the 2022 U.S. House elections, and none of them reached Biden’s margins. And of those six, Democrats only won three this year.

A similar story played out in the state Senate. The party actually had a net loss of one seat in the Senate, a result that seems to have flown under the radar in light of their new House majority. Additionally, there were four Biden-to-Youngkin Senate districts. While all of them swung back to Democrats in 2022, Republican candidates carried three of them this year.

None of this is to suggest that Virginia might suddenly become a swing state in next year’s presidential election. Still, it is curious to see that some of the suburban erosion Democrats experienced in 2021 may be sticking—a possible sign that the leftward swing in these areas during Trump’s presidency may in some places be reverting to pre-Trump voting patterns with the former president out of office. This does mean, though, that if the former president is on the ballot again next year, they could swing back to Biden and the Democrats.

3. Abortion rights continue to win big, though they aren’t a panacea for Democrats.

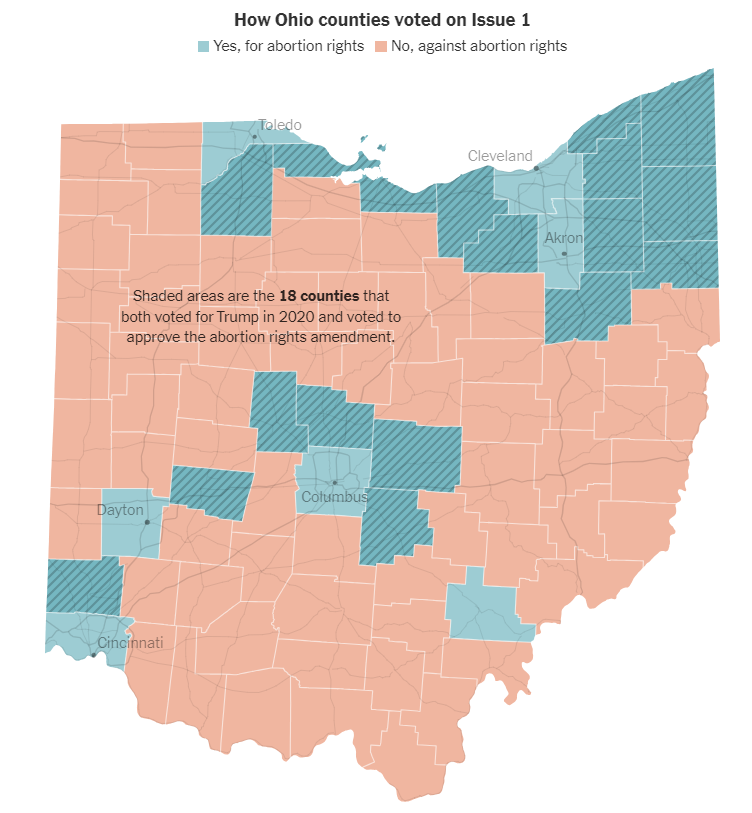

As if the numerous polls gauging Americans’ attitudes on abortion weren’t clear enough, voters themselves have now left little doubt that they support reproductive rights and don’t want the government to infringe on them. Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last summer, voters have passed ballot measures in seven different states protecting abortion access, including in several deep-red ones like Kansas, Kentucky, and Montana. This week, Ohio joined that list, enshrining the right to “make and carry out one’s own reproductive decisions” into the state constitution. In 2020, Biden carried just seven Ohio counties, but fully 25 counties backed the ballot measure, including 18 that broke for Trump. This serves as a reminder that abortion rights are popular among voters who don’t traditionally vote Democratic.

Another state where abortion was on the ballot more indirectly was Virginia, where Republicans led by Governor Glenn Youngkin tried opening the door to a more palatable alternative, offering a proposal to limit the procedure at 15 weeks. But the results in Virginia were far from an endorsement of that policy. Democrats in the state warned throughout the campaign that this proposal concealed Republicans’ true intention to institute a more sweeping ban. The GOP’s 15-week overture ultimately didn’t land with voters, at least not enough to bring a meaningful share of them across the aisle and give their party a majority in either chamber.

Many Americans, including even Democrats, may find acceptable some level of restrictions on the procedure after a certain point in a pregnancy. At the same time, they just don’t seem to trust Republicans to find a middle ground—or stop there even if they do (and with good reason). But even as abortion seemed to aid Democrats this year, it’s important to remember that the context around it matters. In states where limitations on abortion access are imminent, the issue can be more of a motivator, as was the case in both Ohio and Virginia. In 2019, Ohio Republicans passed a six-week ban, which had been held up in the courts among ongoing litigation but is now moot following the passage of Issue 1. And in Virginia, a Republican trifecta could have allowed the party to pass at least a 15-week ban, if not something even stricter.

Nationally, it’s uncharted territory. The upcoming presidential election will be the first since the Dobbs ruling, and it’s anyone’s guess how the issue will play out over the next year. President Biden will likely face off against a former president who appointed the justices that overturned Roe and whose party aims to impose strict abortion restrictions nationwide. Before Dobbs, voters could rely on the courts to thwart any attempt to enact national abortion restrictions—but that’s no longer the case.

Off-year elections also bring out fundamentally different electorates—they tend to be higher-information, well-educated voters. Those who care strongly about abortion rights were probably far likelier to get out and vote this week than were people for whom the issue was not as potent. But in a higher-turnout election like the 2024 presidential, which is bound to draw out people who care about other issues like the state of the economy, Democrats will need compelling messages on these subjects as well. Governor Beshear successfully pulled this off in Kentucky, demonstrating a possible roadmap for the party next year.

4. Democrats show life in Trump country—and find a possible winning formula for the future.

One of the strongest Democratic wins Tuesday was Governor Andy Beshear’s re-election in Kentucky. His victory solidifies a long-term trend in the Bluegrass State: outside of two one-term stints (2003–2007 and 2015–2019), Democrats have controlled the state’s governor’s mansion for the past half century. This dominance has been particularly impressive as the state is otherwise deeply conservative. In 2020, for example, Trump carried Kentucky by a massive 26 points.

Beshear has been a very popular governor throughout his first term. Approval polling regularly placed him among the most widely liked Democratic governors in the country. He received major plaudits for his stewardship of the state economy and his leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic, after the Louisville mass shooting earlier this year, and in the aftermath of 2022 flooding that wrecked parts of southeast Kentucky (areas that notably swung heavily in his direction this year from 2019).

While some may chalk this up to his unique home-state appeal—after all, he won while all other statewide offices broke for Republicans—Democrats can take some lessons from his win. First, swing (or, at least, swingable) voters still exist. Good governance and dealmaking continues to resonate with some voters. Second, Democrats don’t need to shy away from issues where they have an advantage: Beshear stuck to his guns on issues like abortion rights, Medicaid expansion, and public education. Third, he mostly avoided contentious culture war fights and emphasized his commitment to bipartisan cooperation.

This is a template that other red-state Democratic governors such as Laura Kelly have followed—and it’s a sign that while the Democratic brand may be toxic in some parts of red America, it’s not impossible to overcome those issues with the right candidate and message, especially in the face of Republican opponents whom voters perceive to be more extreme.

5. However, they continue to have two big Midwest problems: urban turnout and branding.

While some Democrats appear to have at least partially cracked the code to winning in Trump country, the results in the industrial Midwest this week indicated they have some big challenges to address ahead of 2024. In keeping with trends we have been tracking, it still does not appear that Democrats have solved their urban turnout problem in this part of the country. In Ohio, for example, just 29 percent of the voting-eligible population (VEP) in Cleveland turned out to vote, even as the future of issues like abortion and marijuana were at stake. Notably, the lower turnout here was disproportionately concentrated in the city’s eastern half, which is home to a substantial black population. VEP turnout there was just 25 percent.

The picture wasn’t much better in Pennsylvania, which will host a pivotal contest for president in 2024. Though the votes are still being counted, it appears that turnout in Philadelphia as a share of registered voters is on track to be around 26 percent—lower than for all other counties in the state. The party did offset this with increased turnout in Philly’s collar counties like Bucks, Chester, and Montgomery, all of which also swung left relative to both the 2020 presidential election and the 2021 state Supreme Court election. Still, the race for the presidency next year is expected to be extremely close once again in the Keystone State, and a deflated base (or any rightward movement among the city’s non-white voters) could put the state in jeopardy for Biden.

Additionally, the results in Ohio point to an enduring problem for Democrats in areas like the Midwest: their policies are often popular with voters, but for a meaningful share of these voters, the party’s brand is not. There is just something about the “D” label that many of them react to with visceral disgust—and it doesn’t appear to be (entirely) about policy. Much of this, according to the Democrats’ own self-autopsy, has more to do with “vibes”: the party is perceived as “preachy,” “judgmental,” and “focused on the culture wars.”

Fair or not, this is what Democrats are working against in many parts of the country. To be sure, this is not always an insurmountable problem—strong Democratic candidates have found ways to expand the party’s (or at least their own) appeal in more working-class and rural areas in recent elections. But in 2024, Democratic candidates running in less-friendly places like Ohio and Montana must figure out how to overcome this reality and hit their vote goals in more conservative territory, as Beshear did.

6. These results don’t really tell us much about the 2024 presidential election.

Despite everything discussed above, there’s another important takeaway after this week’s elections: these results won’t be that useful in handicapping the 2024 election. First, these elections were uncharacteristically not a referendum on the party in power—the Democrats. Rather, they were laser-focused on state-by-state considerations. The “status quo” element of this election had to do with the on-the-ground realities in many of these places. In Virginia, most districts broke the way of their baseline partisanship. In Ohio, there was a present threat to abortion rights. In Kentucky, voters approved of their governor and other executive officeholders and made decisions on that basis. In New Jersey, a strongly Democratic electorate sent back a legislature reflecting that. President Biden’s unpopularity and voters’ sour mood about the national economy didn’t seem to have much of an impact anywhere.

More importantly, however, is the reality that turnout is always lower in these contests. As the Cook Political Report’s Dave Wasserman noted, it was down relative to four years ago in Kentucky, Mississippi, and Virginia. Moreover, these elections typically attract voters who are more highly engaged and often college-educated. While this trend historically benefited Republicans, it has turned in Democrats’ favor as the parties’ coalitions have changed in recent years. Off-year electorates like those we saw this week will likely look very different from presidential electorates. Indeed, we have ample evidence that voters who stayed home in the 2022 midterms, for example, are less Democratic-leaning and likelier to vote Republican at the presidential level.

Heading into 2024, Democrats will have to contend with an electorate that is more representative of the whole country. Likewise, President Biden—who is highly unpopular but has also not been a drag on his party’s candidates in the post-Dobbs era—will himself be on the ballot, asking voters for a second term despite all their reservations about him, his mental acuity, and his handling of the economy. He will in all likelihood run against an equally if not more unpopular former president and a Republican Party seemingly intent on taking their unpopular abortion policies nationwide. There is also the uncertainty around various third-party threats lurking in the background.

So, while Democrats have much to celebrate from this week’s results, there is no guarantee that this automatically portends success next November. Given all this, they still have a lot of work to do if they hope to have success next year.