Democrats’ Continued Fixation on Identity Politics Carries Risks

Early signs indicate the party isn’t feeling pressured to change course—again.

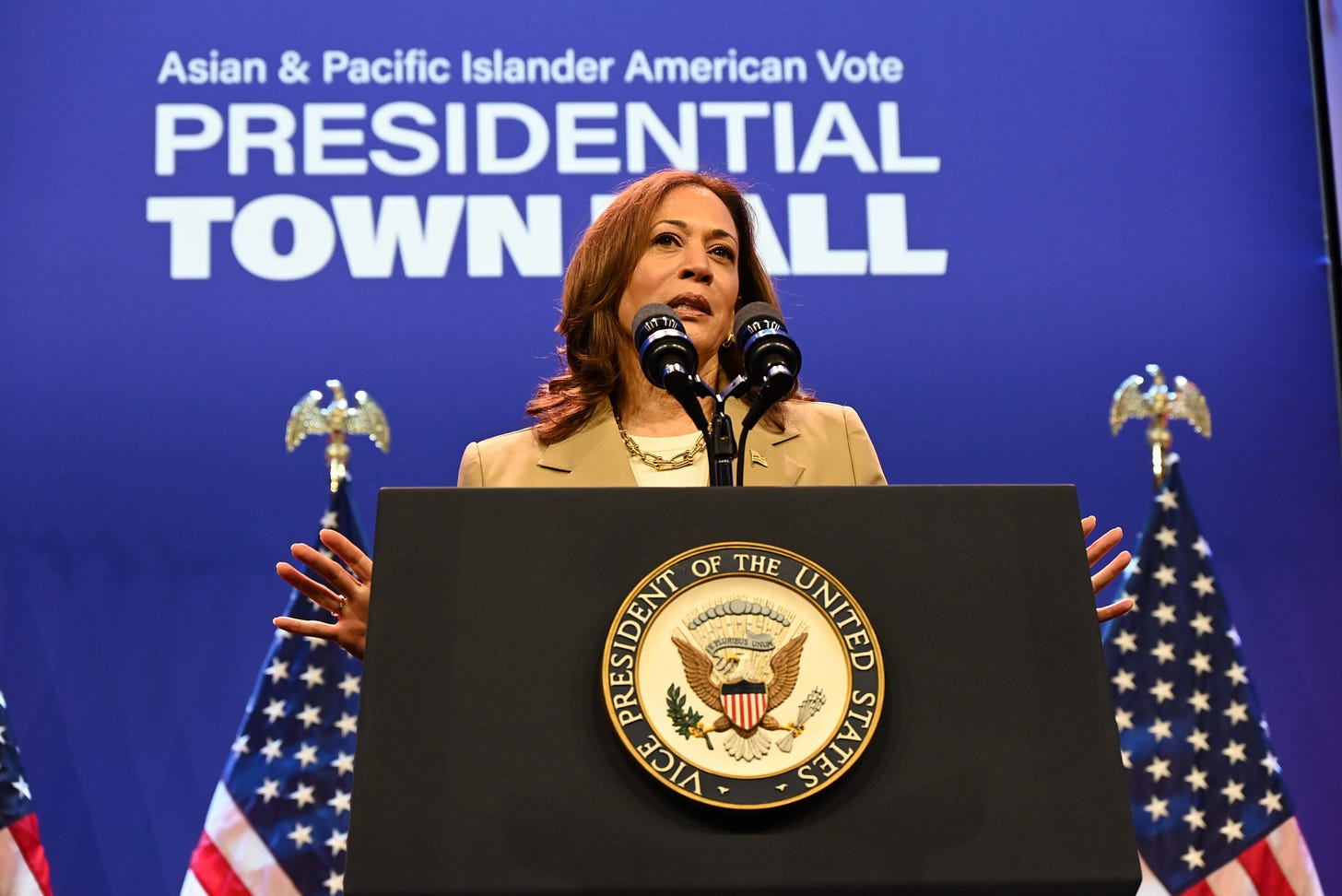

Over the past weekend, Ben Wikler—the current chair of the Wisconsin Democratic Party and one of two leading candidates to be the next chair of the DNC—posted this message to his X account:

Wikler was obviously trying to demonstrate the party’s commitment to groups that have historically been a core part of the Democratic coalition, especially minorities. His post also exemplified a way of thinking that has dominated the party over roughly the past decade: an insistence on seeing the electorate as a collection of identity groups—formed on the basis of shared, often immutable traits—that need to be spoken to individually and treated as distinct from other groups. This is based on the paradigm of “identity politics,” in which people’s sociopolitical attitudes and interests are rooted primarily in their identity traits. However, it is becoming harder to justify using this framework in the year 2025.1

Some will argue that “all politics is identity politics,” and there is certainly some truth to that. Most people vote in what they see as their self interest, and this can be informed by one’s identity. For instance, a person’s religious beliefs, financial status, or sexual orientation may have some bearing on the issues they care about or the politicians whom they believe have their best interest in mind. Similarly, if someone belongs to a group that has historically faced discrimination, that, too, may influence their attitudes and voting behaviors.

But viewing American politics and society through this lens also carries serious risks, especially for political parties, whose primary concern is winning elections.

One such risk is coming to believe that the shared characteristic that binds a group of people together is the most important factor informing that group’s voting habits. A good example of this is the assumption many Democrats have had that immigrants would be so put off by Trump’s demagoguery that relentlessly highlighting his bigoted remarks would move many Hispanics and Asians into their corner. Hillary Clinton operated on this assumption in the 2016 campaign—to no avail.2 But this didn’t stop her party from trying again.

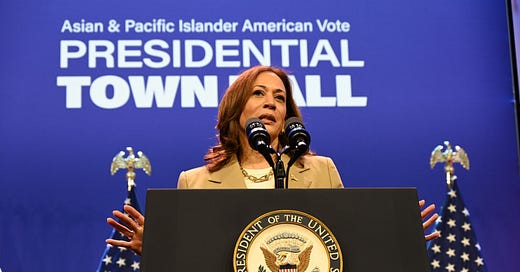

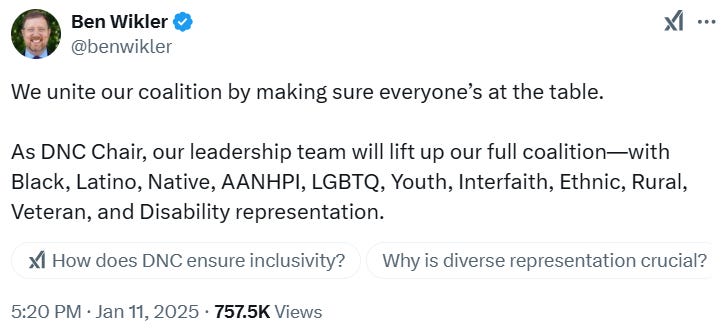

Last cycle, after a speaker at a Trump rally made a crass joke about Puerto Rico in the final week of the campaign, the Democrats thought they had an issue they could use to galvanize Hispanic voters. They put up billboards around Allentown, Pennsylvania, home to a sizable Puerto Rican population, highlighting the speaker’s words. Kamala Harris also hammered home the topic at her final campaign rally in the state.3 But it made no difference. On Election Day, Trump flipped Pennsylvania, Hispanics in the state moved toward him by 14 points, and Allentown and other localities with large Hispanic populations shifted in his direction.

This same thinking has been present in other recent contexts as well. The Biden administration pursued a widely unpopular student loan forgiveness plan in hopes of energizing young voters, despite the fact that student loans were near the bottom of young people’s list of priorities. Harris also clearly hoped that campaigning hard on the abortion issue would move women to support her in record numbers. In the same vein, Democrats touted her race and gender in an effort to boost her support. But in the end, she underperformed Biden with young voters, black voters, and women.

All this is a good reminder that conceiving of any group in monolithic terms risks missing meaningful differences within it. Even terms like “Latino” have limited utility, as they lump the very different life experiences of people with ancestry in, say, Mexico, Cuba, and Colombia into one broad category. In Wikler’s case, his preferred term, “AANHPI” (Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander), does the same thing with people from different countries in different parts of the globe—and often with very different cultures.4 This is perplexing, though, as we were reminded of the importance of understanding the nuances within these populations just last year.

Additionally, when parties and candidates are hyper-focused on messaging to certain identity groups, others then expect to receive the same treatment—and take notice when they don’t get it.

Consider young men. It’s no secret that many have been falling behind their female peers on numerous metrics, including educational attainment and employment. However, there was little in the Democrats’ messaging for men in this past election that matched their much more overt appeals to women. Some Harris surrogates did make a direct pitch to men in the home stretch of the campaign, but they argued that men needed to vote for Harris to show support for the women in their lives. Writing in The New York Times, Michelle Obama pleaded: “I am asking you, from the core of my being, to take our lives seriously.”

The lack of a clear agenda for men hasn’t been exclusive to Harris or her campaign, either. Pollster Daniel Cox has noted that the DNC’s website includes a page called “Who We Serve,” which lists fully 16 different groups they claim to represent. One group conspicuously missing? Men. In light of all this, is it any surprise that they not only didn’t break for Harris but swung to Trump overall by eight points?

Post-election polling showed that the perception that Harris and the Democrats cared more about individual groups than the broader electorate was a real vulnerability for her. A plurality of swing voters said they believed that Harris was “more focused on cultural issues like transgender issues rather than helping the middle class.” Many Democrats protested this, saying that Harris took pains to not talk about such issues on the trail. But this sentiment was likely less about trans issues, specifically, and more in response to the sense that the party talks about issues that affect certain groups at the expense of the electorate’s primary concerns like the economy and immigration.

The point is this: getting bogged down in identity politics often makes it harder to develop a clear and compelling message with universal appeal. People may know that you stand behind this or that group, but they don’t have a good sense of who you are or what you’ll do for them.

What’s strange about the Democratic Party’s almost monomaniacal focus on identity over the past decade is that it’s a stark departure from both its recent past and the ethos that guided one of the party’s most revered figures: Barack Obama. When Obama first came onto the scene at the 2004 Democratic National Convention, his vision for the country explicitly rejected the identity politics paradigm:

[T]here’s not a liberal America and a conservative America—there’s the United States of America. There’s not a black America and white America and Latino America and Asian America; there’s the United States of America.

As he was en route to capturing his party’s nomination in the 2008 primary race, a racially diverse group of attendees at his South Carolina victory speech memorably and spontaneously began chanting in unison, “Race doesn’t matter!” It was a call to embrace the country’s motto—E pluribus unum (out of many, one)—over a more atomized view of the people within it.

Of course, none of this is to say that some groups aren’t disproportionately impacted by certain issues or that politicians should never acknowledge that fact. Ultimately, though, most Americans, regardless of identity, basically want the same things: a general sense of overall stability, a strong economy, good jobs, safe streets and schools, affordable healthcare, and basic respect for their rights.

It shouldn’t be hard to make that case, but doing so requires leaving behind a politics that prioritizes group identity above all else.

Split Ticket’s Lakshya Jain has argued that Wikler was simply appealing to the sensibilities of the DNC members who will decide the next chair. But even if that is true, it is still telling about how the party apparatus continues to think about these things.

Averages of post-election data show she lost ground with both groups relative to Obama in 2012.

Again, these were another speaker’s words, not Trump’s.

It would likely come as a surprise to Indian Americans that they are considered part of the same voting bloc as Vietnamese Americans and people native to Hawaii. On the other hand, this category doesn’t typically include Arabs or Persians, who also hail from Asia.

Lots of plain old common sense here. A couple additional notes: in terms of nonsense categories, “LGBTQ” is as nonsense as they get. This is really a “TQ+” contingent using “LGB” as cover to push an extreme, unpopular, agenda. Allied to this, re the observation that “Many Democrats protested this, saying that Harris took pains to not talk about such issues on the trail.” The problem is that gender identity ideology is well baked-in to the Democratic Party brand (see comment by Wikler, above). What Harris and Walz needed to do was break from that, and to do it out loud. As Bill Clinton said about Title IX athletics: we need to speak to it and say we won’t do it. (This issue has nothing to do with identity, BTW—it is about basic biology.) All of this I write as a longtime, progressive Democrat. The party has lost the plot completely on this stuff, and I don’t think it can win again until and unless it changes course dramatically.

Today's Democrats are too smugly self-righteous and Woke to comprehend that winning coalitions are built upon shared tangible ideas and interests like the economy and security, not on some obscure moralizing feelings promoting diverse identity and shared grievance.

In short, when will this national Democratic Party tire of losing the support of a vast majority of Americans?