Class Conflict and the Democratic Party

Professionals are now Democrats’ core constituency. It’s a problem.

The biggest divide in American politics at present is not along the lines of socioeconomic status (SES), nor educational attainment, nor area type (urban, suburban, small town, rural), nor sex and gender—although these factors all serve as important proxies for the distinction that matters most. The key schism that lies at the heart of dysfunction within the Democratic Party and the U.S. political system more broadly is between professionals associated with “knowledge economy” industries and those who feel themselves to be the “losers” in the knowledge economy—including growing numbers of working-class and non-white voters.

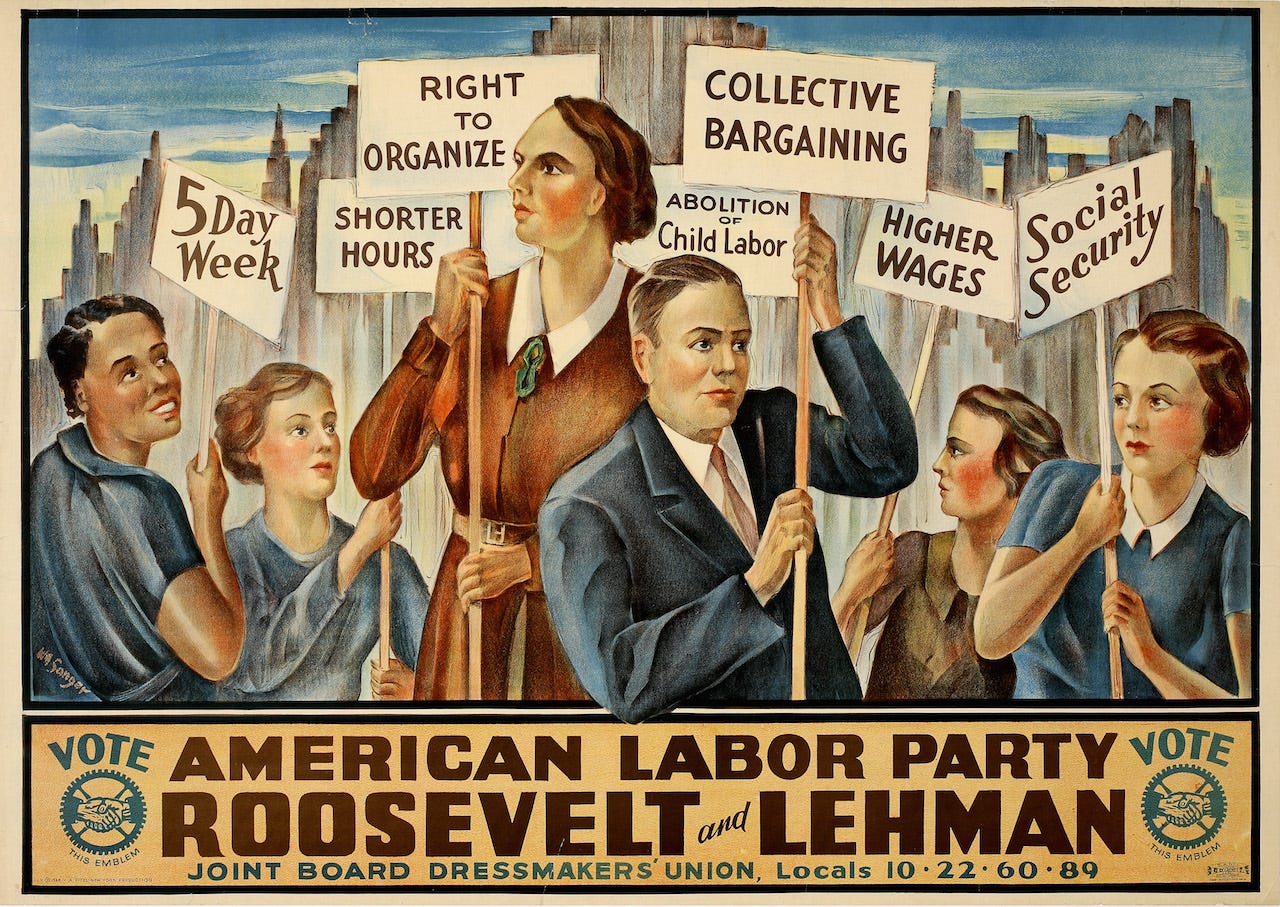

Two decades ago, sociologists Jeff Manza and Clem Brooks observed that “professionals have moved from being the most Republican class in the 1950s, to the second most Democratic class by the late 1980s and the most Democratic class in 1996.” This consolidation has only grown even more pronounced in the intervening years. As professionals have increasingly clustered in the Democratic Party, moreover, they’ve grown increasingly progressive, particularly on “cultural” issues surrounding sexuality, race, gender, environmentalism—and especially when compared with blue-collar workers.

Federal Election Commission campaign contribution data provides stark insights into just how strongly knowledge economy professionals have aligned themselves with the Democratic Party in recent cycles. In 2016, roughly nine out of ten political donations from those who work as activists or in the arts, academia, and journalism were given to Democrats. Similarly, Democrats received around 80 percent of donations from workers involved in research, entertainment, non-profits, and science. They also received more than two-thirds of donations from those in information technology, law, engineering, public relations, or civil service jobs. Among industries that skewed Democratic, the party’s highest total contributions came from lawyers and law firms, environmental political action committees, non-profits, the education sector, the entertainment sector, consulting, and publishing.

Similar patterns held in 2020: the occupations and employers with the largest number of workers who donated to the Biden-Harris campaign included teachers, educators and professors, lawyers, medical and psychiatric professionals, people who work in advertising, communications and entertainment, consultants, human resources professionals and administrators, architects and designers, IT specialists and engineers. Industries that provided the highest total contributions to the Democrats included securities and investment, education, lawyers and law firms, health professionals, non-profits, electronics companies, business services, entertainment, and civil service. Geographically speaking, Democratic votes in 2020 were tightly clustered in major cities and college towns where knowledge economy professionals live and work—and outside those zones, it was largely a sea of red.

The alignment of knowledge economy professionals with the Democratic Party has also shifted the socioeconomic composition of the Democratic base. To give some perspective of how much has changed: in 1993 the richest 20 percent of congressional districts were represented by Republicans over Democrats at a ratio of less than two to one. Today, they tilt Democratic by nearly five to one. The socioeconomic profiles of Democratic primary voters have shifted significantly as well. Counties with higher concentrations of working-class Americans are today a much smaller portion of the Democratic primary electorate than they were in 2008, while counties with large concentrations of affluent households comprise an ever-growing share. This has important consequences for the types of candidates that succeed in primary elections, the language those candidates use, the issues they center, what the party platform ends up looking like and, ultimately, who is drawn to the party and its candidates in national elections (and who is alienated from it).

The increasing dominance of knowledge economy professionals over the Democratic Party has had a range of profound impacts on the contemporary U.S. political landscape. First and foremost, it has contributed to a growing disconnect between the economic priorities of the party relative to most others in the U.S., especially working-class Americans. As sociologist Shamus Khan has shown, the economics of elites tend to operate “counter-cyclically” to the rest of society, meaning that developments that tend to be good for elites are often bad for everyone else and vice versa.

For instance, professionals tend to be far more supportive of immigration, globalization, automation, and artificial intelligence than most Americans because they make professionals’ lives more convenient and significantly lower the costs of the premium goods and services they are inclined towards. Those in knowledge professions primarily see upsides with respect to these issues because their lifestyles and livelihoods are much less at risk—indeed, they instead capture a disproportionate share of any resultant GDP increases—and their culture and values are largely affirmed rather than threatened by these phenomena. Others may and often do experience these developments quite differently.

Likewise, most Americans skew “operationally” left, favoring robust social safety nets, government benefits, and infrastructure investment via progressive taxation, but trend more conservative on cultural and symbolic issues. For instance, they tend to support patriotism, religiosity, national security, and public order. Although they are sympathetic to many left-aligned policies, they tend to prefer policies and messages that are universal and appeal to superordinate identities over ones oriented around specific identity groups (e.g., LGBTQ people, women, Hispanics, and so on). They tend to be alienated by political correctness and prefer candidates and messages that are direct, concise, and plainspoken. Knowledge economy professionals tend to have preferences on these fronts that are diametrically opposed to those of most other Americans, especially working-class voters.

With respect to values, knowledge professionals skew culturally and symbolically “left” but favor free markets. As statistician Andrew Gelman showed, elites in the Republican Party tend to be significantly more liberal culturally and symbolically than the rest of the GOP yet more dogmatic about free markets. Meanwhile, Democratic-aligned elites tend to be significantly more “left” on cultural and symbolic issues than most Democrats but tend to be much warmer on markets. The primary difference between Democratic and Republican elites seems to lie in how they rank free markets relative to cultural liberalism: those who prioritize the former have tended to align with the Republicans, while those who prioritize the latter have consistently aligned with the Democrats. To the extent that highly-educated people support left-aligned economic policies, they tend to prioritize redistribution in the form of taxes and transfers whereas most other voters prefer predistribution—higher pay, better benefits, and more robust job protections so less needs to be reallocated in the first place (typically at the expense of some market freedom).

Critically, although knowledge economy professionals tend to skew more “operationally right” than most Americans, they often have inaccurate understandings of their own preferences. Perhaps counterintuitively, highly-educated Americans tend to be less aware of their own socio-political preferences than most others in society. Typically, we describe ourselves as more left-wing than we actually seem to be. Studies consistently find that relatively affluent, highly-educated, and cognitively sophisticated voters tend to gravitate towards a marriage of cultural liberalism and economic conservatism. However, they regularly understand themselves as down-the-line leftists. As the economist James Rockey put it:

How does education affect ideology? It would seem that the better educated, if anything, are less accurate in how they perceive their ideology. Higher levels of education are associated with being less likely to believe oneself to be right-wing, whilst simultaneously associated with being in favour of increased inequality.

Many knowledge economy professionals support ostensibly “radical” socioeconomic policies, but in a way that prevents even modest reforms. For instance, they tend to be much more critical of capitalism in principle than many other Americans. They tend to support “the revolution” (however defined) in the abstract, but because revolution does not appear to be in the offing anytime soon (certainly not a leftist revolution) they largely carry on day-to-day in much the same fashion as their liberal peers. If anything, under the auspices of slogans like “there is no ethical consumption under capitalism” leftist professionals may show even less willingness to make practical changes in their own lives, institutions, and communities to advance their espoused social justice goals. Individual sacrifices or changes, it is commonly argued, are futile; nothing shy of systemic change is worth aspiring towards.

Consider Occupy Wall Street. Although professionals love to romanticize it as a solidaristic class-oriented movement, in reality, Occupy was anything but. In fact, the framing of the movement helped obscure important class differences and the actual causes of social stratification.

Richard Reeves powerfully argued, “The rhetoric of ‘We are the 99 percent’ has in fact been dangerously self-serving, allowing people with healthy six-figure incomes to convince themselves that they are somehow in the same economic boat as ordinary Americans, and that it is just the so-called super rich who are to blame for inequality.” As Reeves’ research amply shows, the declines in social mobility and rising inequality cannot be well-explained or addressed by simply focusing on the “1 Percent”.

As the economist David Autor emphasized, “the singular focus of the public debate on the ‘top 1 percent’ of households overlooks the component of earnings inequality that is arguably most consequential for the ‘other 99 percent’ of citizens: the dramatic growth in the wage premium associated with higher education and cognitive ability.” In other words, Occupy helped professionals avoid talking about how knowledge economy professions and their employment practices drive contemporary inequality, and how people like them remain the primary beneficiaries of this arrangement.

And rather than focusing on concrete policies to rectify the inequalities they condemned, the Occupy movement’s approach to social change was intensely academic and, in the name of “inclusivity,” outright hostile to politics per se. The movement primarily focused on villainizing those above knowledge economy professionals on the socioeconomic ladder at the expense of advocacy for concrete policies that could tangibly help the marginalized and disadvantaged in society or some actionable platform that could help promote broad-based prosperity.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, knowledge economy professionals were Occupy’s primary base. Despite the diversity of New York City, participants in local Occupy demonstrations were overwhelmingly non-Hispanic white. They were near uniformly liberal in their political orientations and also relatively affluent: roughly three quarters (72 percent) of participants came from households above the New York City median in 2011. A plurality came from households that brought in over $100,000 per year. Seventy-six percent of participants had a bachelor’s degree or higher, and a majority of the remainder were currently enrolled in college. Those who had jobs hailed from overwhelmingly knowledge economy industries. Only about a quarter of employed participants had blue collar, retail, or service jobs.

Across the rest of the country, the picture was basically the same. Occupy protests were concentrated largely in knowledge economy hubs, and there were low rates of participation across the board for those who were not college-educated white and/or liberal—perhaps in part because the operation of the protests themselves was incredibly niche and unappealing to most normies. As Catherine Liu aptly described it:

The highly-educated members of Occupy fetishized the procedural regulation and management of discussion to reach consensus about all collective decisions. Daily meetings or General Assemblies were managed according to a technique called the progressive stack. Its fanatical commitment to proceduralism and administrative strategy suppressed real discussion of priorities or politics and ended up promoting only the integrity of the progressive stack itself. Protecting the stack became more important than formulating political demands that might have resonated with hundreds of millions of Americans whose lives were being directly destroyed by finance capital. [Professional-managerial class]/ New Left ideas about mass movements dominated Occupy’s dreams of politics and limited the effectiveness of its activism. Demographically and politically, Occupy was squarely a PMC elite formation.

In the Occupy protests and over the decade that followed, knowledge economy professionals have regularly paid lip-service to cross-class solidarity. However, they often conceptualize class-based politics in ways that are antithetical to the priorities and values of the lower-income people they purport to champion.

Similar patterns appear in many other issue domains. Knowledge economy professionals tend to be significantly to the “left” of non-whites on issues related to race, and they articulate approaches to race that most non-whites find unappealing. Across the board, they often make strong claims on behalf of various historically marginalized and disadvantaged groups, but these claims are not particularly representative of those they purport to represent.

Given these disconnects, as the Democratic Party has drawn itself closer to knowledge economy professionals it has grown increasingly divorced from the values, concerns, and priorities of most other Americans. As knowledge economy professionals have grown increasingly dominant politically and economically, they have likewise grown increasingly out of touch with the values, perspectives, and priorities of ordinary Americans.

When elites comprise a relatively small share of the population, they are forced to engage with and consider the broader public. In a world where less than three percent of Americans possessed a college degree, as was the case in 1920, it would be impossible for degree holders to simply ignore everyone else. Such a small voting bloc would be unable to control a major political party, orient entire cities around their whims, and dictate the flow of the broader economy in the U.S. and beyond. Indeed, they wouldn’t even be able to keep food on the table if they concerned themselves only with the highly educated.

Today, however, more than one in three Americans over the age of 25 has a college degree. They’re increasingly consolidated into a small number of hubs alongside the wealthy, with tight networks of institutions that reinforce one another such as academia, the mainstream media, advocacy organizations, and left-aligned foundations. Under these circumstances, degree-holders no longer need to engage much with the rest of the country. Knowledge economy enterprises can likewise easily sustain themselves by focusing only on super-elites, other knowledge economy professionals, and the communities and institutions they inhabit in the U.S. and around the world. Academics, journalists, entertainment companies, and other cultural producers can focus exclusively on the culture, values, and priorities of people like themselves and their super-elite patrons with little concern—or even outright disdain—for others. A political party can be flush with funds—and viable electorally—by aggressively pursuing the interests of professionals and the cities in which they congregate at the expense of most others.

For example, voters with a bachelor’s degree or higher have comprised an outright majority of the electorate in Massachusetts, New York, Colorado, and Maryland in recent cycles. Many other states with knowledge economy hubs are trending in the same direction. Studies have found that the effect of educational attainment on Democratic partisanship grows stronger as the share of degree holders in a county increases: as professionals grow less accountable or connected to normies, they align more homogeneously with the Democratic Party.

American cities associated with the knowledge economy are now more uniformly “liberal” than ever, and they tend to be starkly segregated along political lines. According to estimates by Ryan Enos and his collaborators, roughly 38 percent of contemporary Democrats live in “political bubbles” where less than a quarter of one’s neighbors belong to the non-dominant political party—largely as a result of how politically homogeneous most major cities have become:

The most extreme political isolation is found among Democrats living in high-density urban areas, with the most isolated 10 percent of Democrats in the United States expected to have 93 percent or more of encounters in their residential environment with other Democrats…In major urban areas, Democrat exposure to Republicans is extremely low, especially in the dense urban cores. Notably, a large plurality of Democrat voters live in these areas and the very low levels of exposure extend even to the medium-density suburbs of these major areas and to minor urban areas.

The rise of a new major donor class has exacerbated these divides. As David Callahan notes, the transition to the knowledge economy has led to the rise of a new constellation of millionaires and billionaires who retain the traditional aversions to regulation, taxes, trade protectionism, and labor unions of the wealthy classes but who skew far “left” on issues like environmentalism, gender and sexuality, race, immigration, criminal justice reform, and aggressively leveraging the state to address perceived social problems. These new millionaires and billionaires (and their families) comprise a growing share of the super-elite.

Critically, these new knowledge economy oligarchs are not just to the left of the median voter—they are frequently to the left of Democratic activists on these issues who, themselves, tend to be far to the left of the typical Democrat voter on cultural matters. And these super-elites have poured immense sums of money into non-profit organizations, political campaigns, media outlets, and institutions of higher learning to move knowledge economy professionals and their chosen political party further in their preferred direction—quite successfully. As economist Thomas Piketty and colleagues have demonstrated, the new “Brahmin Left” more or less sets the agenda of the contemporary Democratic Party.

Those who feel unrepresented by knowledge economy professionals and their preferred social order—including growing numbers of minority voters—have shifted towards the GOP in response. As Richard Florida has shown, creative class workers moved aggressively towards the Democrats in recent decades and now constitute by far the most staunchly Democratic labor group. Although service class workers still lean left, they have been drifting consistently towards the Republicans since 2008. Meanwhile, working-class voters are now decisively Republican, and have been shifting still further right over time.

This is, in part, because the reorientation of the party around knowledge economy professionals has changed the style of Democratic politics in addition to the substance. As compared to other voters, for instance, professionals tend to be much more impressed by charts, plans, and data, and gravitate towards policy wonk candidates who often hold limited appeal in a general election. Although they are alienating to most other voters, professionals regularly insist upon identitarian appeals to social justice and interpret those who decline to overtly focus on race or gender and sexuality as failing to be “real.” Because our lives are oriented around the production and manipulation of symbols, knowledge economy professionals also place a lot of stock on things like representation, symbolic actions, performative demonstrations, “proper” rhetoric, semantic distinctions, and the like—or what Democratic strategist James Carville derisively described as “faculty lounge politics.” In its bid to attract and mobilize professionals, the Democratic Party has increasingly adopted this kind of messaging.

Even when the party wants to speak to non-elite audiences, its efforts suffer from the fact that the people developing its messages tend to be highly-educated ideologues from relatively affluent backgrounds and often possess inaccurate ideas of what will resonate with their intended audience. When the message itself is solid, moreover the people delivering the intended message—sympathetic media figures, social media advocates, and door-to-door canvassers—themselves all tend to be highly-educated, relatively affluent, and ideologically extreme. And they tend to describe the party, its platform, and its candidates in ways that reflect their own personal values and priorities, often speaking in ways that alienate potential voters. Because the party apparatus is increasingly dominated by knowledge economy professionals from top to bottom, Democrats end up delivering faculty lounge politics even when party leaders would rather not.

The Democratic Party is far from the only organization wrestling with the consequences of knowledge economy professionals’ growing prominence in the political left. From labor unions to the Democratic Socialists of America, many traditionally class-oriented leftist organizations have leaned increasingly into identitarian conceptions of social justice and “woke” symbolic politics because they’re run by knowledge economy professionals who have never worked normal jobs.

Knowledge economy professionals have increasingly embraced these ostensibly class-based organizations in turn. There has been dramatic growth in unionization and union action within higher ed, journalism, tech, gaming, television and movies—even finance! Membership in the Democratic Socialists of America has exploded, driven heavily by young professionals.

But as knowledge economy professionals have gravitated towards these organizations, many others have fled. Union membership in the U.S. is now at a record low. Unions are perceived as increasingly divorced from rank-and-file workers, and more focused on pushing niche agendas of the college-educated folks that administer them rather than protecting jobs or improving pay and working conditions for members. There has been discontent and even lawsuits about the use of union dues to support controversial political organizations like Planned Parenthood and Black Lives Matter or Democratic Party candidates. According to research by political scientist Oren Cass, the top reason non-union working-class Americans mistrust unions is that they are perceived as being too political—and too focused on progressive cultural politics, in particular.

Across the board, catering to the niche preferences and priorities of knowledge economy professionals tends to come at the expense of the allegiance of most others—including and especially working-class voters across ethnic and religious lines. If the Democratic Party has to choose between catering to professionals and virtually any other group, it should prioritize the latter every time.

At present, professionals are basically a captured constituency—the alternative, after all, is the party of Trump. This is a dealbreaker for us in a way that is not true for others. Non-white and less affluent or educated voters are not just willing to cross party lines due to their growing alienation with the Democratic Party, they’ve actually been doing it, in ever-growing numbers, over the course of the last decade—all the way through the 2022 midterms. The fact that labor is now a genuinely contested constituency between Biden and Trump says everything about the current political moment, and it doesn’t say anything good.

Democrats don’t have a lot of margin for error in 2024. And the stakes of this election are genuinely enormous given Trump’s increasingly vengeful and unhinged state. This is not the time to indulge knowledge economy professionals and our idiosyncratic approaches to politics. Democrats should instead focus intensely on normie middle-class and working-class voters and let knowledge economy professionals fend for ourselves. We’ll make our way to the polling places just fine on November 5 next year, and overwhelmingly “vote blue no matter who” all the way down the ballot.

If Democrats want others to join us, they’ll have to meet these others where they are.

Musa al-Gharbi is a sociologist at Stony Brook University and a senior fellow at the Niskanen Center.