Are We Making Progress in Solving the Problems of Distressed Places?

Yes, but only modestly.

As outlined previously in this series on place-based policies, the United States has many distressed places—defined as local labor markets or neighborhoods that are short of good jobs.

Have recent labor market trends improved conditions in these places? Are policymakers effectively addressing these problems?

On the first question: Yes, jobs are moving to distressed places, but not by enough to help much.

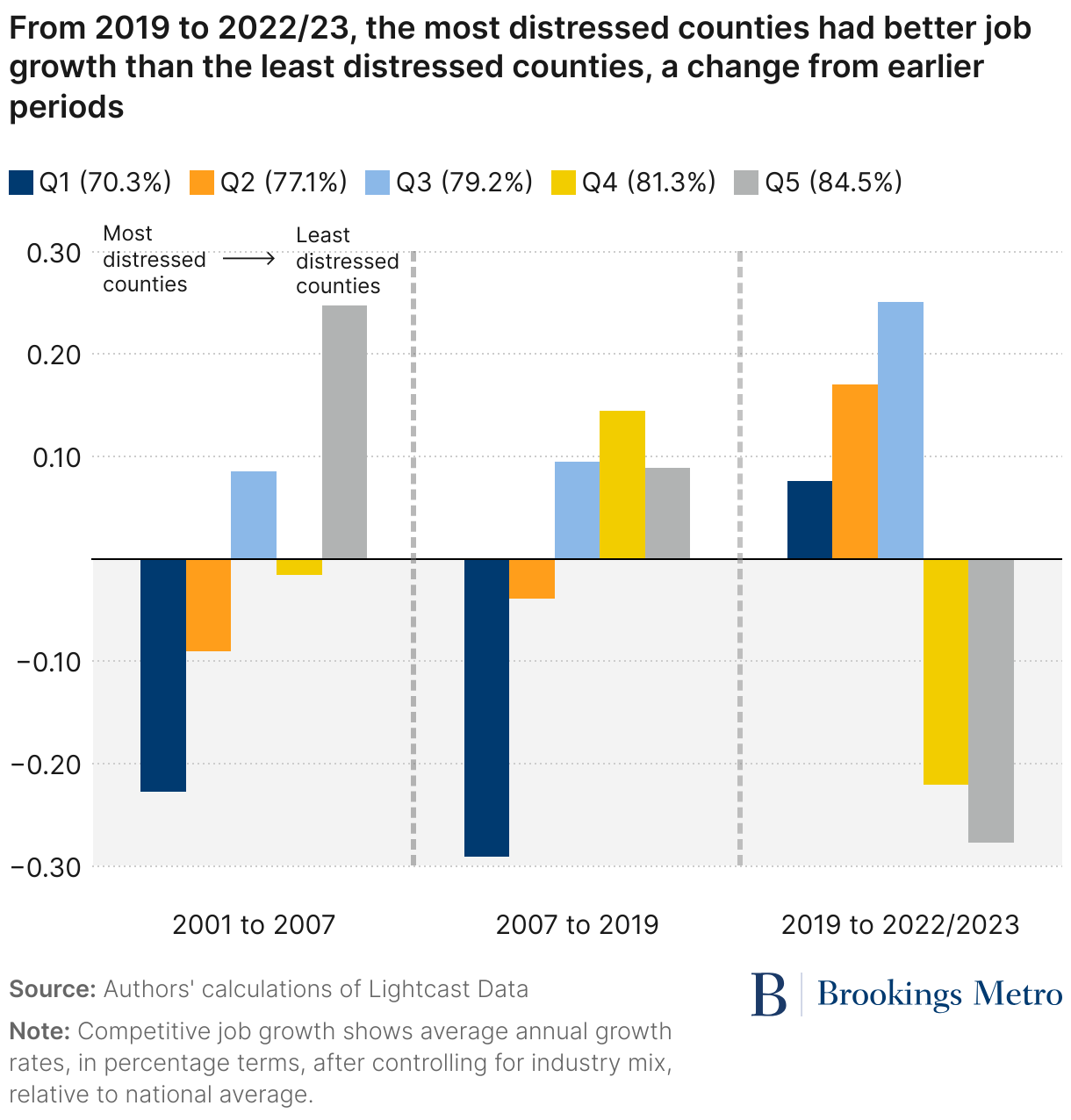

The below chart, from a policy brief I co-authored for Brookings Metro, looks at how job growth varies with county distress.1

Distressed counties’ job growth has outpaced the nation’s job growth from 2019 to the present, reversing the earlier trend.

For the least-distressed counties, in contrast, job growth vastly exceeded the national average from 2001–2007, modestly exceeded the national average from 2007–2019, and fell behind between 2019 and 2023.

As reviewed in our report, these patterns in job growth mirror those in capital investment, which has recently shifted away from the least distressed areas and towards distressed areas.

What is causing these shifts? For slowing job growth in least distressed counties, probably not recent federal policies, as the shifts began prior to 2019. A more compelling hypothesis is that rising housing costs and other expenses in booming high-tech areas have induced job growth to spread out geographically.

The favorable trends for job growth in distressed counties are more recent, however, so they might be due to recent federal policies. Yet, these trends are not large enough to significantly improve job availability. If recent trends continued for 10 years, job growth in distressed counties would outpace national job growth by just 0.8 percent over the decade. In turn, based on past research, this would be expected to increase the prime-age employment rate—the share of people aged 25 to 54 with jobs—by 0.3 percentage points.

A 0.3 percentage point increase in the employment rate would close only a small fraction of the large gaps across U.S. places. For example, based on American Community Survey data from 2022, the United States had a prime-age employment rate of 80.2 percent. But booming areas did even better. The prime-age employment rate in the Washington DC metro area was 85.5 percent, in Nashville it was 84.5 percent, and in San Francisco, 83.0 percent.

Many distressed places were far behind. The prime-age employment rate in 2022 in the Flint (Michigan) metro area was 77.3 percent, whereas Fresno’s (California) rate was 74.9 percent, and Pulaski’s (Kentucky) was only 72.9 percent.

But perhaps recent job growth trends are due to changing federal policies that have only just begun to help distressed places—in the future, could opportunities in these places grow even faster?

As discussed in previous essays in this series, what distressed places need to expand job opportunities is flexible aid able to address each place’s specific challenges. In some places, job creation may be best catalyzed by developing industrial sites with good infrastructure. In other places, investing in education or training will be more effective. In some distressed neighborhoods, jobs may exist nearby but lack of reliable transportation prevents residents from accessing them. In other neighborhoods, child care is a greater issue.

In other words, what Flint needs is not what Fresno needs or what Pulaski needs. One size does not fit all. The best strategies for expanding local job opportunities are comprehensive and customized to a place’s needs.

To date, such flexible aid has been provided only at pilot funding levels. In recent federal legislation, four programs provide truly flexible development aid: the Build Back Better Regional Challenge, funded by the American Rescue Plan of 2021, and three programs authorized in the 2022 CHIPS Act: Tech Hubs, NSF Regional Innovation Engines, and EDA’s Recompete Program.

Each of these programs provides discretionary grants to local areas for locally-designed economic development strategies. Funds can be used for many purposes. The grantees frequently target either distressed local labor markets or distressed neighborhoods within a labor market.

But the funding for these programs is tiny, and goes to few places. The Build Back Better Regional Challenge provided $1 billion total funding for cluster-based economic development strategies, divided up among 21 places. Tech Hubs have received total appropriations of $500 million for high-tech strategies, which will be divided among 31 places. NSF Regional Innovation Engines have received federal appropriations of $200 million for higher education-related economic development strategies, to be divided among 10 places. The Recompete Program has received federal appropriations of $200 million for job creation and job access strategies in distressed local labor markets and neighborhoods, to be divided among 4 to 8 places.

This amounts to total funding of $1.9 billion, split across some 70 communities. The dollars are tiny relative to the need. The Recompete Program alone received 565 applications, requesting more than $6 billion in funding. As I have previously noted, distressed places need at least 2 million extra job opportunities over the next 10 years to significantly reduce their employment rate gap. If these jobs were created efficiently, it might cost $50,000 per job. The total cost would be $100 billion, or $10 billion per year.

Other federal aid programs can help distressed local places, true, but these other sources do not provide flexible long-term support for comprehensive local development strategies. For example, the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund, from 2021, provided $350 billion to state and local governments. Although the funding formula provided higher per capita aid to distressed labor markets, targeting was not ideal, and aid in several places ended up exceeding fiscal needs. Some of this excess fiscal aid probably helped advance local development strategies, but its one-time nature limited its support for projects requiring sustained investment.

As another example, a report by Tony Pipa and Natalie Geismar at Brookings found that in 2020, there were over 400 federal programs relevant to rural development. Post-2020 federal legislation has added another 79 programs relevant to rural development. These programs provide tens of billions of dollars annually. But the aid is neither flexible nor comprehensive, with administration by dozens of federal agencies with more than 30 independent objectives that leave little room for community input.

If the federal government is to efficiently promote job opportunities in distressed places, intergovernmental aid needs a different philosophy. Dedicated long-term funds should support flexible job opportunity strategies that both boost local job creation and improve job access. The purse needs to match the size of the place-based jobs problem, at least $10 billion per year for at least 10 years.

If the federal government does not provide the needed assistance, state governments should step up. There is nothing preventing California from aiding its distressed inland regions, or New York from assisting its upstate regions, except lack of political will.

It is easier politically to fund narrow categorical programs for specific projects that serve particular program interests. It is easier to fund one-time appropriations than to provide dedicated long-term support.

But as argued in a prior essay in this series, it is large-scale, flexible, long-term programs, such as the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Appalachian Regional Commission, that have successfully produced persistent increases in local job opportunities. We need to think big, long-term, and flexibly to solve the problems of distressed places.

Timothy J. Bartik is a senior economist at the Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, a non-profit and non-partisan research organization in Kalamazoo, Michigan. His research focuses on state and local economic development policies and local labor markets. At the Upjohn Institute, Dr. Bartik co-directs the Institute’s research initiative on place-based policies.

This chart is from a Brookings Metro policy brief I co-authored with Katie Bolter and Kyle Huisman. Full methodology is in an Upjohn report. Counties are divided into five groups with equal population after being ranked by their baseline prime-age employment rate (the share of people aged 25 to 54 who have jobs). The report estimates average annual job growth rates for each county group, relative to the nation, after adjusting for each county’s mix of industries, which we label as “competitive job growth.” Most distressed group of counties is on the left for each of the three time periods shown in the figure, the least distressed group of counties is on the right in each of the three time periods, with the other groups arranged so that the baseline distress level in each group of counties increases as we go to the left.

Photo appears to be of Pulaski County, Arkansas ((Little Rock).