Are Hurricanes the Icons of Climate Change They are Made Out to Be?

From "The Climate Report" collaborative series by The Liberal Patriot and The Breakthrough Institute.

In the last few weeks, we’ve witnessed the return of our now annual late summer ritual of attributing hurricane season to climate change. So far, Hurricane Hilary and Hurricane Idalia have both been covered by wide swaths of the media as primarily a climate change story.

One headline reads, rather ironically, “Climate Change Brings Tropical Storm to California for First Time in 84 Years—Are We Ready?”. For Idalia, there’s “Hurricane Idalia: How climate change is fueling hurricanes” (from Reuters) and “How climate change helped fuel Hurricane Idalia” (from CNN).

Speaking on CNN, Bill Weir says:

The cost of [using fossil fuels] is becoming bigger with every storm. Science has been warning about this for a very long time; in many ways, it has been predicted. It is the speed that we’re seeing these changes that has taken most folks by surprise.

But it’s not just the media, either. Speaking about Idalia, President Biden said: “I don't think anybody can deny the impact of the climate crisis anymore.”

This is all in line with a theme that has been eminent since at least the release of An Inconvenient Truth in 2006, which has cover art that not-so-subtly shows a hurricane spewing forth from a power plant smokestack.

But are hurricanes the icons of climate change they are made out to be? What is the true effect of climate change on hurricanes?

Temperature is such a fundamental variable that warming will inevitably have some impact on all weather phenomena. For some phenomena, like heatwaves, the relationship is quite straightforward: heatwaves get hotter as the background climate warms. For other phenomena like hurricanes, however, the relationship is more complicated, depending on the characteristics of the hurricanes involved.

Hurricane characteristics that have been studied include:

Frequency, or how often storms occur;

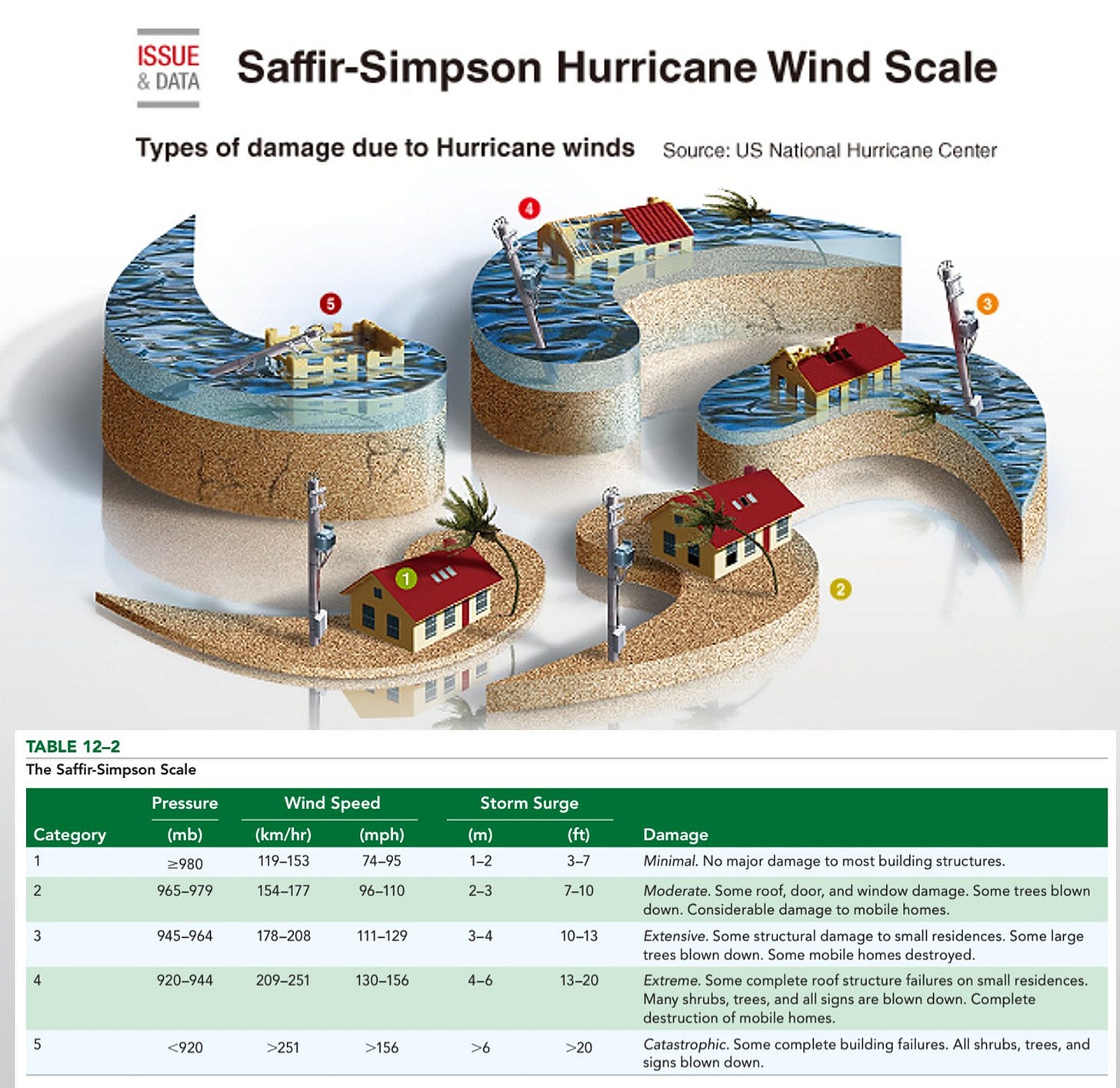

Strength, or their Saffir-Simpson “category”;

Duration, or how long they last;

Size, or how big they are;

Rain rate, or how much rain falls;

Location, or where they occur;

Rate of intensification, or how fast they strengthen; and

Forward movement; or how fast they move.

These characteristics are also studied in the context of different kinds of scientific evidence, which can sometimes be divided into:

Historical trends;

Fundamental theory; and

Mathematical modeling.

Different combinations of characteristics and types of scientific evidence can lead to conclusions about the impact of climate warming on hurricanes that can sound conflicting or contradictory. For example, you might see something that says that hurricane “Accumulated Cyclone Energy”—a measure of total wind speed strength—has not been increasing over time while also hearing that mathematical climate models project that “rapid intensification” of hurricanes will be more likely in the future.

These statements feel like they point in different directions, but they are not necessarily in conflict because they refer to different characteristics of hurricanes (strength vs. rate of change of strength) and different kinds of scientific evidence (historical trends vs. mathematical modeling of the future).

But when considering the grand proclamations from the media and President Biden above, what characteristics of hurricanes and kinds of evidence should we focus on?

If the claim is that hurricane seasons today are something radically different than they have been in the past, then we should focus on historical trends in hurricanes and trends in hurricane strength. So let’s do that.

Hurricanes occur in at least six separate basins worldwide.

The Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State keeps an up-to-date database of global hurricane statistics for each basin. Here is the global number of hurricane days (i.e., the number of hurricanes multiplied by their lifetimes) over the satellite era when we have good records.

Here is the same data but for major hurricanes (Category 3 and above on the Saffir-Simpson scale).

Overall, there is no long-term trend in hurricane days or major hurricane days at the global level. It is important to note that the above trends do not contradict mainstream climate science. The authoritative Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that as it warms,“It is likely that…the global frequency of TCs over all categories will decrease or remain unchanged.”

That’s global, but the North Atlantic Ocean is the one that affects the U.S. and Central America. Here are hurricane days for the North Atlantic going back to the mid-nineteenth century:

And the same for major hurricanes (Category 3 and higher):

Interestingly, the North Atlantic is the only basin that has seen an increase in hurricane activity over a multidecadal timespan (since the 1970s). However, the balance of evidence suggests that the period from the 1960s to the 1980s experienced suppressed hurricane activity because of human-caused aerosol emissions. So the uptick since then is mostly a recovery to the more 'natural' level of activity. The IPCC summarizes the situation as follows:

It is virtually certain that there are increasing trends in North Atlantic hurricane activity since the 1970s with medium confidence that anthropogenic aerosol forcing has contributed to these trends.

“Aerosol forcing” refers to the reductions in mostly sulfate aerosol pollution causing local warming.

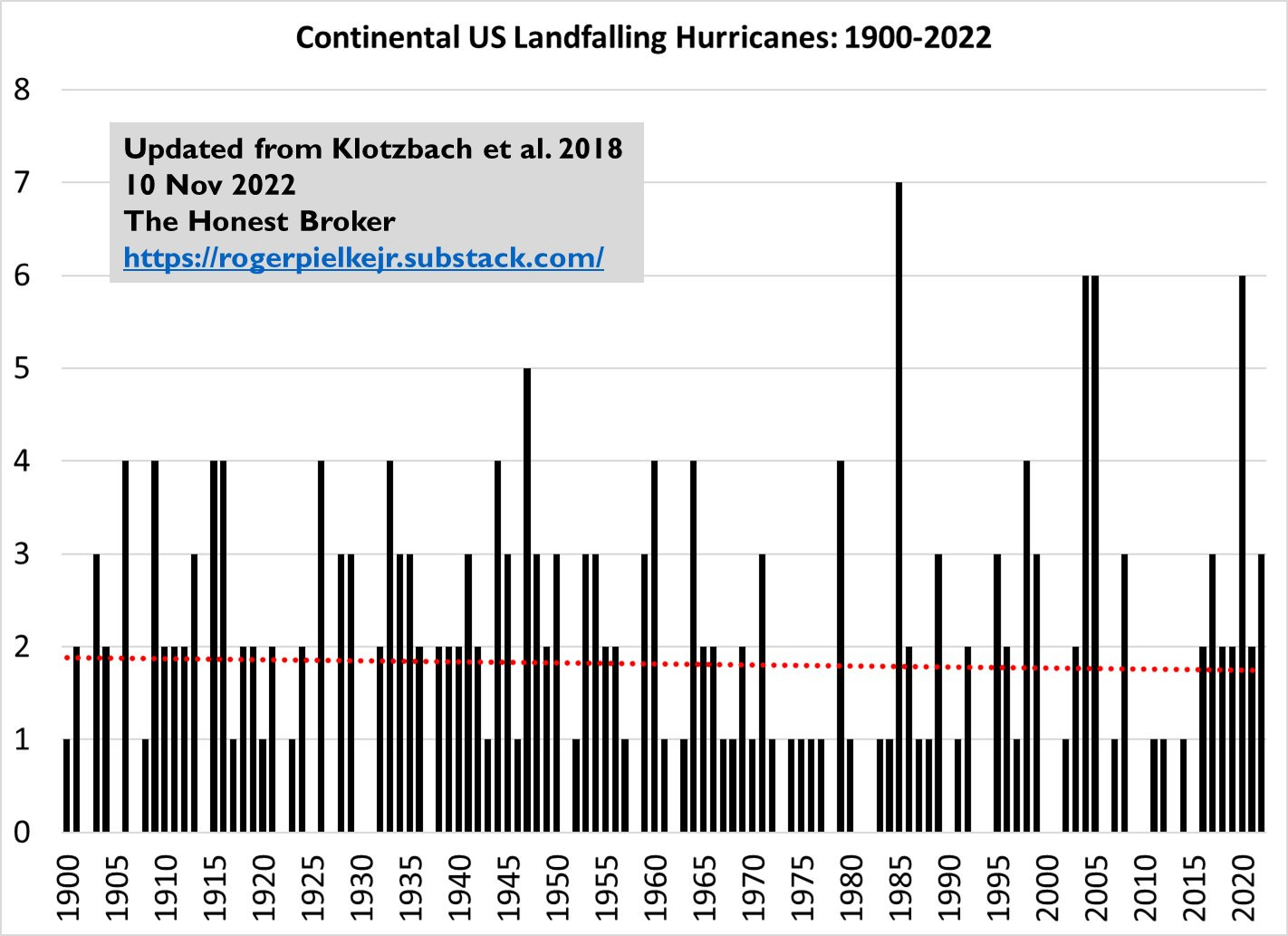

Of course, hurricanes out at sea are relatively harmless—it’s landfalling hurricanes that we care the most about. Here’s the historical record of landfalling hurricanes for the US:

Again, we see no obvious long-term trend.

So looking at the frequency and strength of storms tells a very different story than that told by a lot of the media and politicians. But are frequency and strength the only things that matter? No.

Other characteristics of storms certainly affect their impacts as well. In fact, there is strong support from all three kinds of scientific evidence listed above (observations, fundamental theory, and mathematical modeling) that warming is increasing the maximum rain rates in hurricanes by about 10 to 15 percent per degree Celsius. On this point, the IPCC states:

Event attribution studies of specific strong hurricanes provide limited evidence for anthropogenic effects on hurricane intensifications so far, but high confidence for increases in hurricane heavy precipitation. There is high confidence that anthropogenic climate change contributed to extreme rainfall amounts during Hurricane Harvey (2017) and other intense hurricanes.

Thinking about increased rainfall in the context of Idalia, its highest totals were around 10 inches, and human-caused climate change has caused late summer Gulf of Mexico waters to be about 0.75°C warmer than they would have been in preindustrial times. This means that we expect rain rates for Idalia to be enhanced by about ten percent [(13 percent/°C)*0.75°C = ~10%]. So this means that ten inches of rain from Idalia would have been closer to nine inches of rain in the absence of climate change.

Due to sea level rise, moreover, warming has caused storm surges to be higher than they used to be. Global mean sea levels have risen by about nine inches since 1900, and relative trends around the Florida Gulf Coast are near this global average. That means Idalia’s maximum storm surge of about ten feet in some places would have been a storm surge of nine feet three inches before human-caused climate change.

Overall, then, we see no clear trends in hurricane frequency or intensity. But there is evidence that when hurricanes do occur, they can produce something like ten percent higher rainfall totals and ten percent larger storm surges than they would have in the 1800s. That’s not nothing, but it’s not a reason to make hurricanes the poster child for the effects of climate change.

Instead, I think the evidence indicates that the vast majority of the risk we face from hurricanes is due to living in a climate that naturally produces hurricanes—not due to a warming climate. When science communicators, the media, and politicians strain to view all extreme weather through the lens of climate change, it only serves to misinform the public and inadvertently undermines the credibility of the underlying science.

Patrick T. Brown is a Ph.D. climate scientist, co-director of the Climate and Energy Team at The Breakthrough Institute, and adjunct faculty at Johns Hopkins University.