To the surprise of some, voters in both red and blue states, including Florida, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Massachusetts, recently rejected ballot measures to legalize recreational marijuana and psychedelics—breaking the trend of approval of such measures by voters in many states across America over the past couple decades.

In the face of public discontent with crime and other community harm like loss of public spaces to open drug use stemming from the decriminalization of hard drugs, voters and policy makers in states and cities on the West Coast reversed course. Even before the recent election, politicians were talking tough on drugs again.

This is evidence of another transitional or “weird moment” in the history of drug policy in our country. But sometimes a weird moment can bring clarity and opportunity to evaluate the mistakes of the past and move forward with changes that are based on evidence of what actually works and delivers the best outcomes for both individuals and communities.

Thankfully, there are many evidence-based tools in our drug policy tool box that allow government officials to craft policies based on results. These tools should not be viewed as switches to turn on and off, but rather as dials to adjust to achieve the best overall results. The components of a tough but smart approach include:

Prevention. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” said Benjamin Franklin. Prevention is a key component of demand reduction. But this dial was turned down significantly in many parts of our country, in part as an understandable reaction to well-intentioned but ineffective or even harmful pseudo-prevention programs of the past, such as “Just Say No.” But modern prevention programs for our youth, based on science, can be quite effective and some of the most meaningful drug policy dollars we can spend. There are also more precise modern programs that increase the awareness among youth regarding the recent proliferation of potentially lethal high-potency drugs that sometimes masquerade as pills for experimentation. Prevention is not a panacea, but it should no longer be marginalized or overlooked as part of the policy mix.

Enforcement. An overemphasis on enforcement can lead to some of the worst aspects of the so-called “War on Drugs,” such as the mass incarceration of drug users. But, used correctly, law enforcement is essential to ensuring that community harm from drug use, such as property crime driven by addiction, or the loss of public areas to drug use, is minimized. Furthermore, much like impaired driving diversion programs that have proven so successful, many evidence-based drug diversion programs, such as deflection, conditional discharge, probation, or release to treatment, rely upon law enforcement as the triggering mechanism. Law enforcement is also necessary to effectively address drug dealing, property crimes driven by addiction, and overt drug markets. For those committing such crimes due to their own addiction, diversion programs with high levels of accountability, such as treatment courts, can simultaneously offer a path to recovery and a reduction in crime. Law enforcement is vital to stopping individual and community harm from drugs and should no longer be shunned or marginalized.

Treatment. Drug treatment works when grounded in reality and evidence-based approaches. That does not mean it works for everyone, every time. Addiction can sometimes be incredibly difficult to overcome. Multiple episodes of treatment are sometimes necessary. Relapse is also common. When cancer reoccurs in a patient, we don’t say: “Well, we tried treatment and that didn’t work.” Instead, we resume treatment, often with adjustments. There are many forms of addiction and many forms of treatment. Some work better than others, depending on the individual, the particular drug of addiction, and the circumstances. We know a lot more about the science of addiction than we did even a few short decades ago. Our treatment options have therefore evolved to provide better outcomes. Traditional counseling sessions, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, work for some. For others, contingency management or medication assisted therapy works better. Combining approaches can also be quite effective, such as contingency management in the context of diversion.

Recovery support. “I’m not telling you it’s going to be easy. I’m telling you it’s going to be worth it,” as a peer in recovery might say to a person suffering from addiction. Evidence-based programs to support recovery from addiction are still as vital as ever. Many people find this support essential to maintaining recovery. There are many peer support programs available, such as traditional 12-step and narcotics anonymous. These should be further encouraged to expand into underserved communities.

Harm reduction. The overreliance on harm reduction as a remedy to the overreach of the “War on Drugs” has created its own set of harms that the public is rightfully now rejecting. This dial is now in the process of being turned down in some parts of the country, most notably large cites that adopted a harm reductionist approach in replacement of enforcement. But, used properly, some harm reduction programs are essential to saving lives, such as making naloxone, a drug that can rescue a person from what would otherwise be an opioid overdose death, readily available. There is also an aspect of harm reduction that has been shunned by some purists, primarily because it utilizes law enforcement—namely, community harm reduction such as focused deterrence to eliminate overt drug markets. Instead of being pushed to the side, community harm reduction should be significantly expanded throughout the nation.

Supply reduction. American drug policy has often overemphasized and allocated enormous resources to supply reduction efforts that have been, at best, ineffective. But opposition to some effective supply reduction approaches has been overstated. While it is true that border controls by themselves are ineffective in significantly reducing the supply of street drugs in our country, effective border control can and does raise the cost of street drugs, which then translates to higher prices and lower overall harm. More importantly, the supply of street drugs has long shifted to powerful synthetics. This affords an opportunity for supply reduction through effective international precursor controls, which has only recently been reprioritized after years of shifting focus to harm reduction.

In addition to focusing on an evidence-based national drug policy, we should also reevaluate the basic framework of federal drug laws that arise from two acts of Congress originally passed in 1938 and 1970, respectively. We’ve been putting band-aids on those laws ever since. It’s time we examine whether that framework is in the best interest of public health and safety, or whether it has unfortunately better served the financial interests of industries built around them.

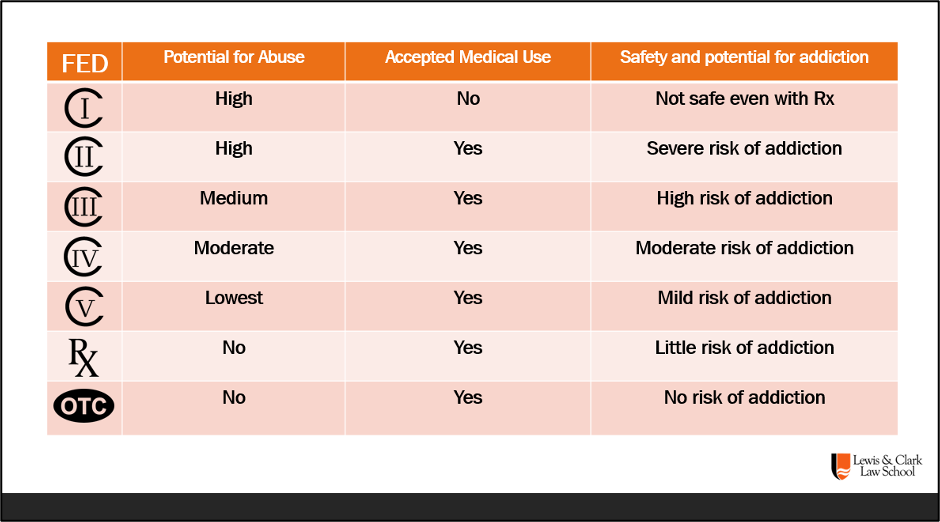

For example, the way we decide which drugs are subject to which sets of controls and regulations leaves behind many important considerations. An oversimplification of the seven categories and three criteria we currently use looks something like this:

As a result, any drug deemed to be without medical utility is placed in Schedule I and prohibited. But this also serves to shut down virtually all federal funding for research into whether those drugs might actually have some potential medical use that has not yet been determined. This has happened to both cannabis and psychedelics.

For drugs deemed to have an accepted medical use, safety and addiction are taken into account, as is potential for abuse. But community harm is not a factor in the categorization. This has led to absurdities, such as the relative placement of marijuana as a Schedule I controlled substance, as compared to meth and fentanyl, which are on Schedule II.

Social acceptance is also not taken into account. A majority of states have passed laws legalizing and regulating medical or recreational cannabis under state law, even in the face of federal Schedule I prohibition. Without any cohesive federal cannabis policy, more harm occurs in the vacuum ranging from Congress accidentally legalizing interstate commerce in cannabis that can be turned into impairing products without addressing the downstream impacts on states and communities to under-regulation of key aspects of the cannabis industry by some states to the proliferation of high potency cannabis products without any regulatory framework to address public health and safety concerns.

Our current drug regulatory framework also lacks accountability to separate the public interest in health and safety from the financial interests of those that are supposed to be regulated. This is why the pharmaceutical industry can cause an epidemic of prescription opioid abuse and addiction that directly fed into our current fentanyl crisis, or prevent the adequate regulation of drugs diverted to make more dangerous drugs, or why pharmacy industry middlemen can inflate prices and drive independent drug stores out of business.

The current “weird moment” in the history of our drug laws and policies affords us the opportunity to shift to a national drug policy based on evidence and analysis, build public trust and confidence, and deliver the best outcomes for individuals and communities—if policy makers are willing to look at what works, drop what doesn’t, and commit to helping Americans and their communities across the country.

Rob Bovett is the Vice-Chair of the Oregon Criminal Justice Commission and teaches Drug Law and Policy at Lewis & Clark Law School in Portland, Oregon. His career has focused heavily on creating and implementing diversionary programs in the justice system for people suffering from addiction or behavioral health issues.

Living in Colorado I got to see first hand the ups and downs of legalisation.

Some good things were it brought a bunch of money to the state, rental incomes in the mountains went up a lot as growers moved in. Mom and pop growers were able to supplement their incomes in illegal but also unprosecuted grows. Pot smokers stopped getting busted.

The downside was criminality. Criminals from Texas and other states moved in, began large illegal grow operations. They were the same people selling coke and fentanyl in other states. People maybe not great to have around. Lots of cash, security goons. If you've ever been around criminals you know what I'm talking about. As a contractor I encountered these folks, cash customers, shady.

I have nothing against pot as a recreational drug, or at least it's less destructive than booze, but it's not all peace and love.

Recreational drug abuse is a product of two things. First, despair in both ghetto and holler brought on by the economic destruction of globalism. Stop and roll back that and you have made a start. The second-youthful stupidity-is harder to address since it has been around since the dawn of time. People have abused some form of brain eradicator ever since the first caveman discovered fermented grain. Hell, even elephants and robins abuse drugs. But can we at least suppress the relentless propaganda by Hollywood and mass culture. Notice that both of these are demand side solutions like the best of your solutions. Supply side, law enforcement and harm reduction strategies will be needed short term because things have gotten so out of control.