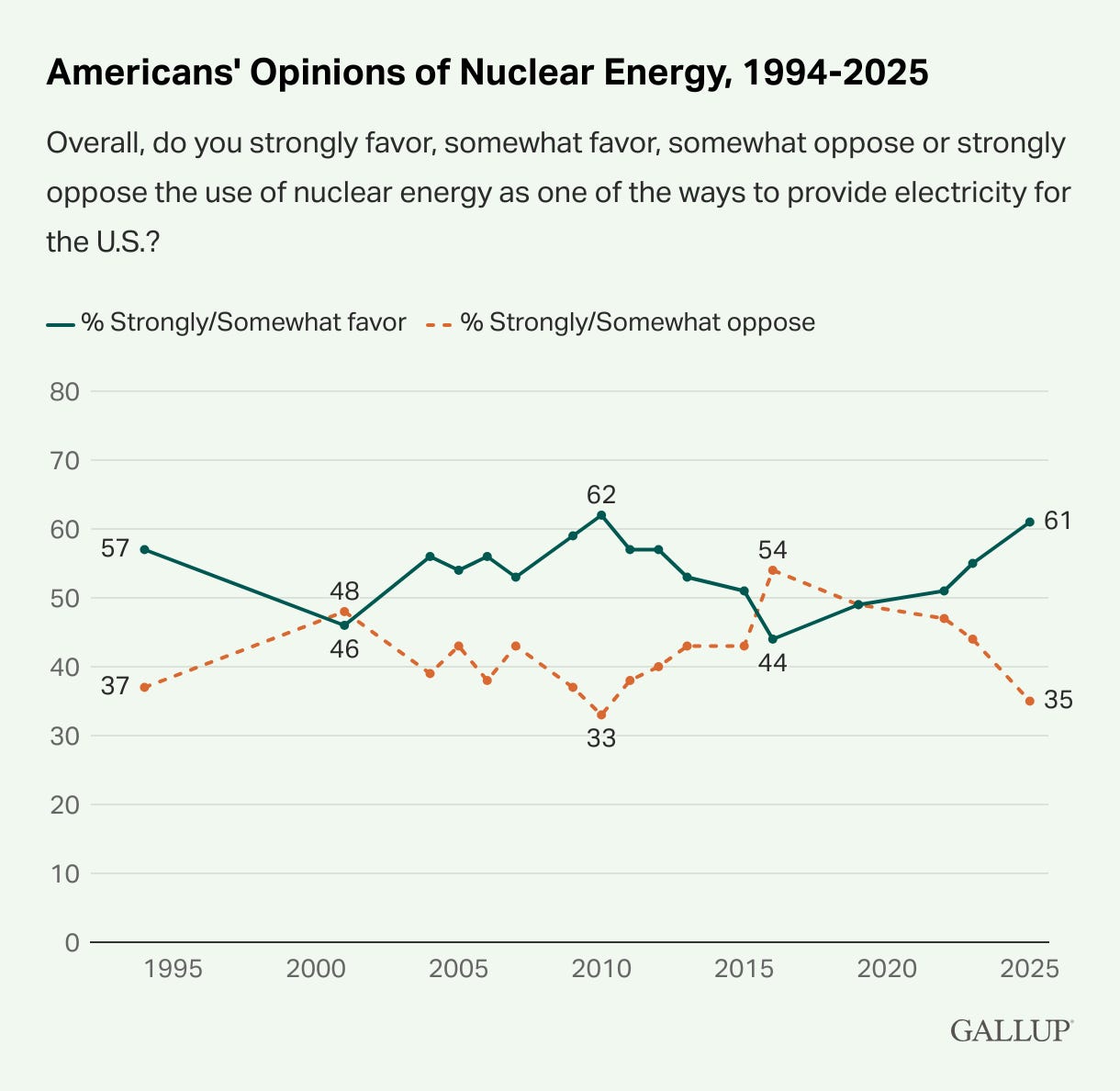

This just in: Americans love nukes! New Gallup data show attitudes toward nuclear energy doing a U-turn from negative views in the mid-teens to strongly positive views today. In less then 10 years, positive views have spiked by 17 points while negative views have plummeted by 19 points. That’s taken net support (favor minus oppose) from -10 to +27.

This is surprising but it’s worth asking why this is surprising. Nuclear power, after all, is a clean, carbon-free energy source in an era when the center-left is obsessed with eliminating carbon emissions. Moreover, nuclear can provide the necessary firm, baseload power to the grid that intermittent renewables (wind and solar) cannot. So where is—or has been—the love?

The answer goes back to the origins of the modern environmental movement and the apocalyptic strain that always lurked there, ready to be activated by an issue like nuclear power and, later, climate change. Here you need to make the acquaintance of a man named William Vogt.

Vogt was an ornithologist and ecologist whose experiences in the developing world had convinced him that economic growth and overpopulation would inevitably lead to civilizational collapse unless both growth and population were radically curtailed. He published his book-length polemic Road to Survival in 1948.

Vogt’s book had an enormous impact. It was a main selection of the Book of the Month Club, condensed by Reader’s Digest for its 13 million subscribers, translated into nine languages and immediately adopted as a textbook by dozens of colleges and universities. It became the best-selling book of all-time on environmental themes until the 1960’s and the publication of Silent Spring.

Vogt argued that humans were worse than parasites, who lacked enough intelligence to be truly destructive. But humans had used their brains to rip up nature and compromised their own survival to become richer. Only drastic measures could prevent worldwide environmental disaster (sound familiar?).

Vogt argued that beliefs in progress were weighing humanity down and were actually “idiotic in an overpeopled, atomic age, with much of the world a shambles.” He concluded that the road to survival could only lie in maximizing use of renewable resources and accepting lower living standards or reduced population.

In his language and outlook, one can see all the strands of apocalyptic environmentalism that were brought to bear, first on nuclear power, then on climate change. This especially applies to his description of the United States and its economic system. He said:

Our forefathers [were] one of the most destructive groups of human beings that have ever raped the earth. They moved into one of the richest treasure houses ever opened to man, and in a few decades turned millions of acres of it into a shambles.

He continued:

’Free enterprise has made the country what it is!’ To this an ecologist might sardonically assent, ‘Exactly.’ For free enterprise must bear a large share of the responsibility for devastated forests, vanishing wildlife, crippled ranges, a gullied continent, and roaring flood crests. Free enterprise—divorced from biophysical understanding and social responsibility.

Vogt’s outlook was enormously influential. Historian Allan Chase observed:

Every argument, every concept, every recommendation made in Road to Survival would become integral to the conventional wisdom of the post-Hiroshima generation of educated Americans…[They] would for decades to come be repeated, and restated, and incorporated again and again into streams of books, articles, television commentaries, speeches, propaganda tracts, posters, and even lapel buttons.

More benignly, Vogt’s book marked the evolution of traditional conservationism into environmentalism. Stripped of the apocalyptic verbiage, he was arguing that conservation of nature was not enough. The interdependence of man and nature meant that human activities could not be isolated and instead were having negative effects on the entire planet—wilderness, settled areas, oceans, everywhere. The balance of nature was being destroyed, dragging down the natural world and humanity with it. Restoring that balance, not merely conserving parts of the ecosystem, was the new meaning of being an environmentalist.

Also key to Vogt’s analysis was the concept of “carrying capacity”—how much the environment/planet could sustainably bear of a species’ imprint before disaster ensued. This was not precisely defined but it is easy to see the relationship of this idea to how climate change is conventionally thought of today.

The modern environmentalist movement kicked off in the early 1960’s with the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (as with Vogt’s book, a Book of the Month Club selection). Carson was directly inspired by Vogt and in fact was a friend of his. Her book was primarily focused on the impact of synthetic chemicals, especially DDT and other pesticides, on the natural environment. Her prognosis was dire; not only were these chemicals destroying the balance of nature by disrupting ecosystems but they were also destroying the ecosystem of the human body. These chemicals have “immense power not merely to poison but to enter into the most vital processes of the body and change them in sinister and often deadly ways.” Moreover, these chemicals would “bioaccumlate” and have enhanced effects over time. Perhaps eventually even the birds would not sing (producing a “silent spring”).

The serialization of the book in The New Yorker took the middlebrow educated audience by storm. The chemical industry fought back, which only raised the profile of the book. The public furor led to a report on pesticides by President Kennedy’s Science Advisory Committee which, in 1963 issued a report largely sympathetic to Carson’s analysis. The general issue of pollution of the natural environment by commercial processes and chemicals received a huge boost from the intense and prolonged public discussion and from this the modern environmental movement was born. Protecting the environment and natural systems now had a truly mass base.

A wave of reforms duly followed. There was a blizzard of legislative action to protect the environment and roll back pollution. That began under LBJ with the Clean Air Act, Solid Waste Disposal Act, Water Quality Act, and Air Quality Act. Then under Nixon there was the National Environmental Policy Act, proximate to the Santa Barbara oil spill and widely-publicized Cayahoga River fire, establishing the (NEPA) environmental standards and reviews that are still with us today. Also under Nixon, the Environmental Protection Agency was established, the Clean Water and Endangered Species Acts passed and the Clean Air act strengthened. The first Earth Day was on April 22, 1970, clearly marking the environmental issue as a mass cause for those on the left of the political spectrum.

An interesting aspect of all this activity is that it was meliorist and profoundly reformist. That is, despite its origins in the Vogtian Silent Spring, with its apocalyptic overtones, the drive to clean up the environment was pursued through a steady accumulation of legislation and consciousness-raising about the issue. There was a sense that the problem was solvable through such activities and did not require the massive changes in economic activity and human behavior that an advocate like Vogt would have called for.

But despite these astounding early successes of modern environmentalism, the apocalyptic strain of the movement was simply lying dormant. Given the fundamental contradiction between man and nature, between human economic activity and ecological balance that is assumed by environmentalism and its intellectual origins, it was only a matter of time before an issue or issues arose that rekindled that strain.

The first such issue was nuclear power. From the beginning, opposition to nuclear power was closely linked to opposition to nuclear weapons. The same things that led people to demonstrate against nuclear bombs—deadly radiation and catastrophic explosions—drove people to oppose nuclear power. Surely those plants, since they relied on the same technology that produced nuclear explosions, could easily pollute the environment with radiation and potentially destroy surrounding communities.

The issue was a natural fit to the burgeoning environmentalist consciousness. The first activist group dedicated to the issue was the Citizens Energy Council, founded in 1966, which argued that nuclear power plants were intrinsically unsafe and a health hazard. As the sixties moved into the seventies and nuclear power plants were being rapidly rolled out, opposition grew and was seamlessly blended into the general environmentalist portfolio. If you considered yourself an environmentalist, you also likely opposed nuclear power.

An additional spark for the movement was provided by the early 1970’s energy crisis. This brought home to Americans the need to ramp up the domestic energy supply. This development helped popularize the thinking of environmentalists like anti-nuclear, anti-fossil fuel economist EF Schumacher (Small Is Beautiful) and, particularly, Amory Lovins, whose influential Foreign Affairs article, “The Road Not Taken”, built directly on the chaos of the energy crisis to argue that America faced a choice between two paths, the “hard” path, relying on nuclear and fossil fuels (the policy at the time) and the “soft” path that would twin the “benign” energy sources of wind and solar with energy conservation and efficiency. That would both solve the energy crisis, he claimed, and lead to a much better eco-conscious society.

Lovins’ arguments had wide purchase within the environmental movement and the allied and frequently coterminous anti-nuclear power movement (environmentalist organizations like the Sierra Club, Greenpeace, and others had already declared their opposition to nuclear power). His analysis brought together environmentalism, anti-nuclear power, and reverence for wind and solar in one big package that quickly became conventional wisdom in activist circles and the wider public they were preaching to.

The apocalyptic strain already visible in the anti-nuclear power movement was turbo-charged by the Three Mile Island incident in 1979. No one died in the incident and the safety systems held, but it is fair to say the event scared the hell out of many people and, of course, the anti-nuclear power movement had a field day. The movie, The China Syndrome, had been released right before the incident and the eerie coincidence further amplified the effect of Three Mile Island on the popular imagination. Nuclear power was cast as a matter of life and death, with the Big Explosion and radiation poisoning always, and inevitably, right around the corner.

Then, of course, there was Chernobyl in 1986 and Fukushima in 2011. From 1978 to 2012, no new nuclear power plants were authorized in the United States. The build-out of nuclear power in the country essentially stopped. The anti-nuclear power movement could not eliminate nuclear power entirely but they did largely succeed in the goal of preventing the expansion of nuclear power (already plagued by cost overrun problems) through political obstacles and a super-stringent regulatory process.

Fast forward to today where the public mood is shifting in favor of nuclear power. The Vogtian climate change movement has been forced to admit that ruling out nuclear power makes no sense if the goal is to decarbonize as fast as possible. Indeed, getting rid of nuclear power in states and countries (such as Germany) has only succeeded in slowing progress toward that goal. Moreover, the concept that advanced societies can and should be engineered to zero out carbon emissions by various dates certain has been steadily losing credibility. Target after target is being walked back as the realities of energy and economic systems have started to bite. Turns out getting rid of carbon emissions is really hard!—especially if, unlike Vogt, you don’t want to radically reduce living standards.

That’s creating a lot more room in the public discourse and among policymakers to think rationally about how to structure energy systems and discard the hard date targets which Vaclav Smil correctly characterizes as “delusional”. More generally, as my AEI colleague and co-author Roger Pielke, Jr. remarks, we are probably exiting the stage of peak climate alarm and attention; that can be nothing but good for the quality of discussion on energy issues.

The climate movement is a product of North America and Northern Europe…The ‘climate first’ voter is a tiny slice of the political landscape, even though they occupy a lot of attention and time on social media, in universities, and until recently, in the global financial sector. They made a lot of noise, but there weren't a lot of them around to begin with. The climate is just not that important to very many people around the world. People will say it's important. But give them a list of topics and it routinely comes in 17th, 18th, 19th, out of 20…

One story for the future of the climate discourse and climate change is that it's not going to go away, but it's going to fade from the center of public view like overpopulation did….

There's a pretty well-known economist named Anthony Downs who wrote a famous paper called the Issue Attention Cycle…It’s like a bell curve. You discover there's a potential problem, there's a lot of excitement, and ‘We’ve got to do something about it!’ Everybody gets on the bandwagon. Then you realize, ‘Oh my gosh, this is difficult! This is challenging!’ And then your attention goes to somewhere else and it's back down. And really climate change is following the Downs’ Issue Attention Cycle perfectly.

Nuclear fits very well into this evolving issue space. Peak climate alarm was so closely tied to a relentless focus on renewables that it made it hard to fairly consider other energy sources. Now, as the premier source of clean, firm power, nuclear increasingly seems like a no-brainer for any energy system seeking to both provide energy abundance and move away from carbon emissions over the long run. Policymakers are recognizing this as country after country, including the United States, has committed to ambitious new nuclear programs. The public is absorbing this vibe shift as the Gallup data indicates.

This is not to say the Vogtian climate change movement has completely given up on opposing nuclear power. Many climate-oriented NGOs still oppose nuclear and even those who have don’t offer only the most grudging, hedged support. The same applies to the community of climate activists; more of these activists are willing to reluctantly admit that nuclear may have a role play—but that admission is very reluctant and sits very far down their list of issues to work on.

This hopefully will change over time. It’s probably a bit much to expect these activists to accept the ineluctable reality that fossil fuels, especially natural gas, will be with us for a long, long time. But pushing nuclear energy would be a way they could continue their commitment to decarbonization while dialing down their maximalist demands around a renewables-based rapid energy transition.

In this way, nuclear could help provide a desperately needed off-ramp to energy realism for the both the Vogtian climate change movement and the center-left parties whose policies have been so influenced by the movement. The Vogtian paradigm has outlived its usefulness; it is time to come full circle and resuscitate one of its first casualties. The broader environmental movement and the world will be better for it.

Great analysis from Ruy Teixeira. These modern-day flat-earthers on the Left have done more to actually setback any hope of U.S. energy independence than Three Mile Island ever could have.

Forward on multiple energy fronts, nuclear foremost among them if only to play catchup with demand.

See? Now reading this entire account, understanding what happened, how it started, the events that made it worse and better has just allowed me to do something I always want to do, but can't. I am able to understand where these people are coming from, I can see myself in their cause when I was younger. Basically, it allows me to humanize people I generally write off as bonkers. I wish more topics would be covered this way. You have a way of writing that doesn't put a thumb on the scale.