As the dust settles on last week’s election, we are starting to get a clearer picture of exactly what happened. It’s important at this stage not to draw sweeping conclusions about these results, as the early data is often incomplete and not always reliable. In the months ahead, we’ll get more and better data in post-election studies, including from the data firm Catalist and Pew Research Center. However, the data we do have point to some overarching trends that are worth examining further.

Harris’s loss is consistent with an anti-incumbent theme seen around the world. One important piece of context to this election is the fact that incumbent parties in democracies across the globe have struggled mightily this year—and even that may be an understatement. According to the Financial Times’s John Burn-Murdoch, 2024 marks the first time since 1905—essentially, since the dawn of modern democracy—that every governing party in a developed country lost vote share. There appears to be a wave of populist outrage sweeping through the developed world right now, leaving incumbent parties in a precarious state. Much of this anger likely stems from the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Voters really, really hate inflation (and uncontrolled migration, too). In pre-election polling from Gallup, voters said that the economy and immigration were the two issues they cared most about—and they trusted Republicans more than Democrats to handle them. Gallup’s analysis showed that since 1952, the party with an advantage on the electorate’s top issue(s) had won the presidential election every single time. This proved prescient: this year’s AP VoteCast survey found that among a list of nine different issues, Trump was only favored over Harris on those two—but they ended up being by far the most important ones. Nearly 40 percent of voters identified the economy as the top issue facing the country, and they voted for Trump 24 points (61–37 percent). Another 20 percent said it was immigration, and they broke for him by an even wider margin, 88–11 percent.

Biden was an albatross around Harris’s campaign. After four years of Biden’s presidency, his approval rating was underwater, nearly two-thirds of Americans thought the country was on the wrong track, and a majority of the country said they were “worse off” compared to four years ago for the first time since at least 1984. Biden’s decision to drop his re-election bid in July gave Democrats a renewed sense of hope that even in this environment, they might be able to stave off a second Trump term by running a younger candidate who could prosecute a better case against him. Instead, Harris spent much of her time trying to outrun the shadow of her highly unpopular administration, with little success. According to a post-election Blueprint poll, four of the five top reasons that voters gave for not picking Harris related to their frustrations with Biden’s presidency. It also likely didn’t help matters that Harris said there was “not a thing” she would have done differently from Biden during his time in office.

Harris also struggled to outrun her past unpopular positions. Throughout the campaign, Harris was reluctant to address head on her past left-wing positions on issues ranging from abolishing private health insurance to confiscating certain guns to decriminalizing border crossings, often instead falling back on the line, “My values haven’t changed.” One of the positions that dogged her most in this election was her previous support for taxpayer-funded sex-reassignment surgeries for detained migrants. The Trump campaign highlighted her stance in one of their last ads of the cycle, saying she was “for they/them” while Trump was “for you” in an effort to portray her as too liberal. For her part, Harris dodged journalists’ questions about whether she still agreed with that position, simply saying she would “follow the law.” It became one of the most effective ads of the cycle: in testing, the ad shifted the race 2.7 points in favor of Trump after viewers watched it, and it was ultimately the top reason swing voters gave in deciding not to vote for Harris.

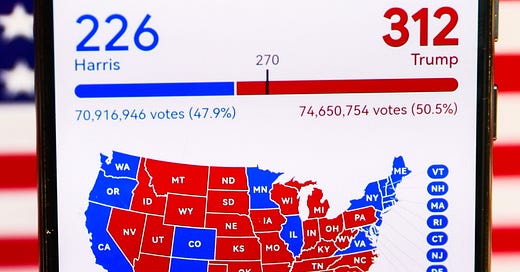

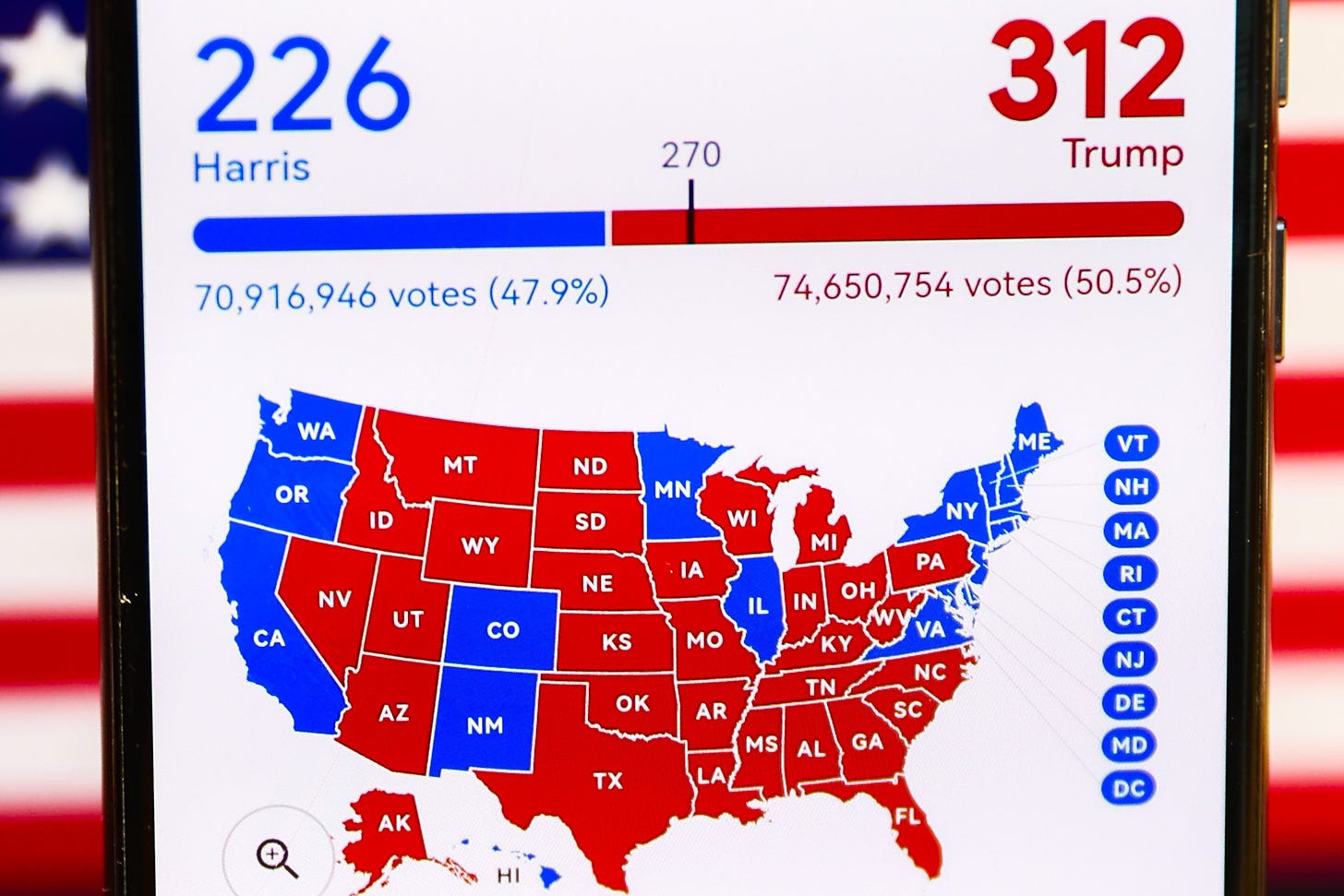

Harris’s campaign seemed to have had some positive impact. Even as the country on the whole swung right from 2020, the shifts were less pronounced in the core swing states. As of November 10, Harris had essentially matched Biden’s vote total across six of these seven states (Arizona was still counting), receiving 99.8 percent of his total votes in 2020. By comparison, in all non-battleground states that had finished counting, she had earned just 89.2 percent of Biden’s votes. This was a sign that perhaps her sustained campaign in the swing states—a campaign that hammered home an economic-focused message—may have had an impact on the final result. Trump ultimately won because he was able to increase his vote total from 2020 in the swing states that decided the race, hitting 105.6 percent.

Abortion did not give Democrats a boost. One of the issues on which Democrats had a clear and consistent advantage in this election was abortion, and they worked to press that advantage in hopes of offsetting their deficits on inflation and immigration. Harris’s ads in the home stretch of the campaign were disproportionately focused on the issue. Democrats also placed measures protecting abortion rights on the ballot in several states with the hope that they would mobilize voters to their side. However, while most of these states backed the measures, it didn’t dissuade voters there from also supporting Trump, including in the key swing states of Arizona and Nevada. Nationally, a plurality (38 percent) of voters said they believed abortion should be legal in “most cases,” and Trump won fully 40 percent of them.1

The country is experiencing growing racial depolarization. One of the more notable trends of the past decade has been the declining levels of non-white support for Democrats—and correspondingly higher levels of support for Republicans. Since the passage of the Voting Rights Act, Democrats have long received overwhelming backing from racial minorities, especially black voters. During his presidency, Obama set high-water marks with black (95 percent), Hispanic (70 percent), and Asian (68 percent) voters. Since then, however, Donald Trump has made inroads with each group. This cycle, early returns indicate that Harris’s margins over Trump hit their lowest level with Asians since 2004, the lowest level with black voters since 1976, and the second-lowest level with Hispanics ever. At the same time, she matched Biden’s margin with white voters, representing an improvement from 2016 and 2012.2 Although lower levels of racial polarization in voting are arguably a good thing for America, it’s clear that at least for now, Democrats are on the losing end of that development.

At the same time, the class divide is growing. For a few years now, we at The Liberal Patriot have been covering the changing nature of the Democratic Party—specifically, how after being perceived as the party of the working-class for decades, Democrats have slowly morphed into the party of the professional class. Today, they have hit their highest margins of support on record with both college-educated voters and those making at least $100,000 a year. Meanwhile, the Republicans are taking this opportunity to pick up the mantle as the party of the working class. This year, they won voters making under $50,000 for the first time ever and carried non-college voters by their highest margin on record. They also continued chipping away at the Democrats’ advantage with union-household voters. If the Democrats wish to retain their identity as the party of the common man and woman, they’ll need to figure out a way to not just stop but reverse these slides.

The gender gap among young people is real and growing. One of the biggest questions leading up to this election was whether we would finally see a long-expected gender gap among gen Z voters materialize—specifically, whether young women would grow more Democratic while their male counterparts grew more Republican. Historically, both young men and women have been Democratic-leaning groups. In 2020, men aged 18–29 were the only male age cohort to back Biden, doing so by 15 points. Meanwhile, every female age group supported Biden, and he won the youngest cohort by 32 points. This produced a gender gap of 17 points. In 2024, that gap nearly doubled: young women supported Harris, though by a smaller 18-point margin, but young men broke for Trump—and did so by 14 points. This created a gender gap of 32 points. As this generation ages and becomes a plurality of the electorate, this divide could have a profound impact on not just future elections but American society as well.

Change elections are the new norm. Between 1960 and 1998, American politics at the federal level was fairly stable. Partisan control of the presidency, Senate, and House only changed hands occasionally, and it most often occurred in presidential years. However, for a plethora of reasons, that reality has changed over the last two decades. Since the turn of the century, only twice has the country experienced an election in which none of those three institutions flipped to the out-party: 2004 and 2012. It’s a sign of the turbulent political era in which we currently live—and why although Republicans earned themselves a governing trifecta this year, they shouldn’t expect it to last long.

This is something we warned about early last year.

Again, we’ll have to wait for better data in the spring to confirm these trends.

Where is the Bob Woodward book on who was actually the president the last 4 years while Biden was mostly a figurehead? I think the sense that we were lied to for four years is real, and that Democrats only acknowledged the truth when George Clooney said it was ok to. Look at Biden’s entire career / nothing about it lines with with his lurch to the left on every issue, particularly immigration, but also the extreme DEI and relentless extreme trans stuff. The “interview” with Dylan Mulvaney is a particular low point that Joe Biden of the previous 40 years wouldn’t recognize.

What is a bit strange is that none of these points were unknown before the election so nobody should have been very surprised by the results